One of the most fascinating halakhot of Shavuot is a halakha that isn’t: a commemoration of the historical aspect of the day, the “day of the giving of our Torah”, as we say in our prayers.

All three major holidays have three aspects: historical, agricultural, and Temple ritual. Pesach is historically the time of the release from Egypt, agriculturally the time of the barley harvest, which is marked in the sanctuary by the Omer offering. Shavuot is historically the time of the giving of the Torah, agriculturally the beginning of the wheat and fruit harvests, which are marked in the sanctuary by the “Shtei HaLechem”, the two loaves of wheat bread, and by the beginning of bringing the first fruits (Bikurim) to the base of the Mizbei’ach. Sukkot is historically a commemoration of HaShem’s protection of the Jewish people in the desert, when we lived in temporary dwellings and were protected by Divinely-provided clouds of glory.

Agriculturally, it marks the end of the summer and the gathering of most of the harvest; in the Temple, the agricultural aspect is recalled by the water libation and other customs which relate to our need for rain for future harvests.

Pesach and Sukkot both have mitzvot which relate to their historical aspect. On Pesach we are commanded to tell the story of the Exodus, and to eat matza and eliminate chametz to recall the haste of our departure. On Sukkot we dwell in booths to recall our sojourn in the desert. But on Shavuot there is no specific practice that recalls the momentous historical event that the day commemorates: the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai to the entire people!

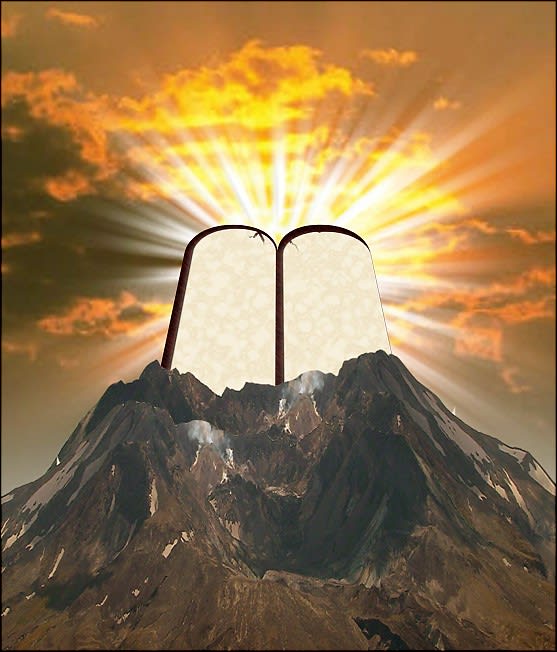

A similar void is that nowhere in the Torah is it stated that Shavuot commemorates the giving of the Torah, although chronologically it is clear from the verses that it is very close. In fact, the historical circumstances are so shrouded in mystery that we do not have enough information from the Torah to determine exactly where Mount Sinai is, and to this day its identity is unknown.

It seems that the Torah intentionally de-emphasized the historical dimension of Shavuot. One profound explanation is that giving this day too much of a historical aspect would relegate the giving of the Torah to a distant, isolated event: one day, long ago, HaShem appeared to the Jewish people and transmitted the Torah. This happened in a specific time (Shavuot), at a specific place (Mount Sinai), and through a specific individual (Moshe Rabbeinu). Yet we are obligated to experience the giving of the Torah as an eternal, ongoing process. Every morning we say a bracha acknowledging that HaShem “gives the Torah” – in an ongoing way. At all times, and at any place where Torah is taught, HaShem gives the Torah through all the Torah teachers who continue the chain of tradition which began with Moshe but which continues through all the generations. In order to inculcate this consciousness, the Torah did not give enough information to ascertain precisely when or even where this event took place. “Matan Torah” cannot be commemorated because it is unceasing.

This column is based on a shiur of Rabbi Josh Berman.

Rabbi Asher Meir is the author of the book Meaning in Mitzvot, distributed by Feldheim. The book provides insights into the inner meaning of our daily practices, following the order of the 221 chapters of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.