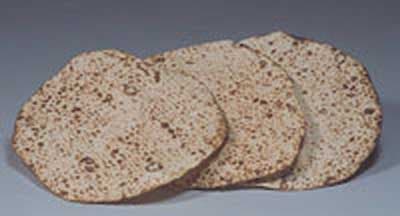

The Shulchan Aruch states that it is forbidden to eat a bread meal from the tenth hour onward on Erev Pesach (SA OC 571:1). (Of course the reference is to matza ashira, matza made with juice or wine rather than with water; regular matza, of the kind that fulfills the commandment to eat matza at the seder, is forbidden all day.) The reason is so that we may eat the seder meal, and particularly the matza, with appetite.

A similar rule exists for Shabbat eve (SA OC 249:2). The difference is that on Shabbat, it is merely praiseworthy to refrain, whereas on Pesach there is a complete prohibition. Similarly, on erev Shabbat it is preferable for a very sensitive person to fast the whole day (ibid), but on erev Pesach the Shulchan Arukh describes this as an obligation. (SA OC 470:3.)

The gemara explains the difference between these two rules, stating that the prohibition on Erev Pesach is because of “the obligation of matza” (Pesachim 99b). Rashi explains that matza should not be eaten when we are already sated, and adds that eating matza is an absolute Torah obligation.

The simplest understanding is that the stringency of erev Pesach is one of degree. On Shabbat eating is merely one fulfillment of a general mitzva of Oneg Shabbat, Shabbat delight; furthermore, this mitzva is of Prophetic, not Torah, origin. Therefore, we have to be extra careful to have appetite for the matza.

However, we can also explain that there is a fundamental difference in the character of the eating. In fact, there are three distinct levels of eating: Shabbat meal, Yom Tov meal, and Seder meal.

The most lenient of all is Shabbat. The reason is that eating on Shabbat is not a mitzva per se; it is rather a means to the end of Shabbat enjoyment. The Shulchan Arukh states explicitly that if a person finds food repulsive, then he may fast on Shabbat since food detracts from his Shabbat delight instead of adding to it (SA OC 288:2). This rule is not mentioned regarding Yom Tov.

On Yom Tov, eating is also a means to an end, but the end is not only personal enjoyment but also a way of adding dignity and importance to the day. In previous columns we have likened the Yom Tov meal to a dinner made in someone’s honor; it is possible to merely have a ceremony but having a dinner adds importance. A person invited to such an event doesn’t refrain from eating merely because he is not hungry! Likewise, eating on Yom Tov is a way of showing honor to the day.

On Pesach, eating the matza is a positive commandment in and of itself. Even if a person doesn’t like matza, and even if no honor is added to the meal (a person can honor the meal with matza ashira), he is required to eat it. Therefore, unique preparations are made to enable a person to eat the matza with some appetite (specifically, the halachic restriction on meals in late afternoon.)

Rabbi Asher Meir is the author of the book Meaning in Mitzvot, distributed by Feldheim. The book provides insights into the inner meaning of our daily practices, following the order of the 221 chapters of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.