The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

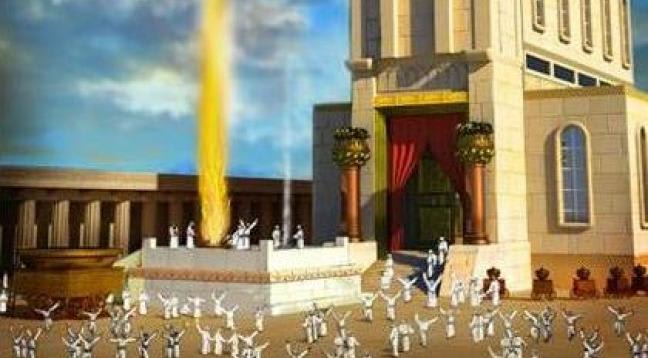

Zevachim 86a-b: More mistakes in the Temple

In the first Mishnah of this perek, or chapter (daf 83a ) we learned – based on the passage in Sefer Shemot (29:37 ) which teaches that “anything that touches the altar will become holy” – that animals that are appropriate for sacrifice will become fully sanctified if they are brought onto the altar, even if there is a problem that would, ordinarily, cause them to be invalid for sacrifice.

The Mishnah on today’s daf extends that law to other cases. Here we learn that this same rule applies to the ramp leading up to the altar – the kevesh – as well. Similarly, the Temple vessels – the klei sharet – also will serve a similar function, and anything that enters them will become sanctified. The source for this is the passage referring to the vessels of the Tabernacle that teaches that the vessels became sanctified and that all that came into contact with them became sanctified, as well (see Shemot 30:29 ).

In truth, not everything that comes into contact with these things becomes sanctified.

Just as the first Mishnah in the perek makes clear that this law does not apply to everything that is brought to the altar, but only to animals that are ra’uy lo – those that are appropriate for sacrifice – similarly the only things that become sanctified from contact with the kevesh or the klei sharet are things that are ra’uy lahem. Thus, as the next Mishnah (see daf 88a ) explains, Temple vessels that are used for liquids (e.g. blood, wine, oil or water) will not sanctify solids that are placed in them and those that are used for solids (e.g. flour) will not sanctify liquids that are placed in them.

Another caveat that should be noted is the idea that there is a difference between the type of sanctification that is conferred on the things that are brought to the altar or its ramp as opposed to things that are placed in the Temple vessels. Once a sacrifice is brought to the mizbe’ah or to the kevesh, it cannot be removed and is sacrificed. On the other hand, when something is placed in a keli sharet it is not fully sanctified; it simply can no longer be redeemed.

Zevachim 87a-b: Air rights over the altar

As we have learned (on daf 83 , and on yesterday’s daf, as well) animals that are appropriate for sacrifice will become fully sanctified if they are brought onto the altar – or onto the ramp leading up to the altar – even if there is a problem that would, ordinarily, cause them to be disqualified for sacrifice.

The Gemara on today’s daf raises the following question: Does that rule apply to the air above the altar? If an animal that is disqualified from sacrifice is placed above the altar, does it also become sanctified to the extent that it cannot be removed from the altar and must be sacrificed?

In response to this question, the Gemara points out that the same law of keivan she-alu, shuv lo yerdu – once they were elevated onto the altar, they cannot be brought down – applies not only to the altar, but to the ramp leading to the altar, as well. If the air above the ramp does not have the same level of holiness as the ramp itself, then how could such a sacrifice be transported to the altar? Once the kohen lifted it off of the ramp, he would have abrogated the rule that once the animal reaches the altar, it cannot be removed from it! Clearly the air above the altar has the same status as the altar itself.

The Gemara rejects this proof by arguing that the kohen might have to drag the animal up the ramp, keeping it in physical contact with the ramp at all times.

In response, the Gemara points out that there was a gap between the ramp and the altar, and the kohen would surely need to lift the sacrifice at that point in order to transfer it from the ramp to the altar. This, too, is rejected by the Gemara, which argues that the gap was small enough that at all times the majority of the sacrificial animal was either on the ramp or on the altar.

The Gemara’s conclusion is that the air above the altar – and the ramp – has the same status as the altar itself, a position accepted by the Rambam as the halacha (see Rambam Mishnah Torah Hilkhot Pesulei HaMizbe’ach 3:12).

Zevachim 88a-b: Dirty laundry in the Temple

The Mishnah on today’s daf (page) mentions in passing that when one of the Temple vessels develops a hole, it is not fixed, rather it is replaced. A baraita brought by the Gemara expands on this theme, teaching that when a knife that was used for slaughtering sacrifices became nicked it was replaced, rather than sharpened, and if it became loose from its handle, that also would not be repaired.

What about priestly clothing that became dirty? A second baraita is brought that teaches that the uniforms worn by the priests in the Temple were woven rather than sewn and that when they became dirty they were not washed with cleansing agents like netter or ahal. This statement is clarified by Abayye who explains that if the uniform became lightly stained so that water would clean it, then netter or ahal could be used; if, however, cleansing agents were needed, then it could not be washed at all. Others rule that these uniforms were never washed, they were always replaced since ein aniyut bimkom ashirut – because there is no poverty in a place of wealth, i.e. in the Temple, a place of wealth, activities appropriate for the poor were not practiced.

It appears that netter is Sodium Carbonate (Co2Na2). Sodium is found naturally in desert areas, but in the ancient world it was often extracted from kelp. It dissolves easily in water, and the mixture creates a strong base reaction due to hydrolysis, causing fat to break up. For this reason it was commonly used as a cleansing agent beginning in biblical times.

There are several plants in Israel that are called ahal. One of them – ahal ha-gevishim (Mesembryantnenum cristalimum L.) – is an annual plant that grows among rocks and on walls that face the sea. This plant contains large amounts of soda, which was used for bathing and washing clothing.

Zevachim 89a-b: Setting priorities in the Temple – I

The tenth perek of Masechet Zevachim, which begins on today’s daf is called Kol HaTadir – “Whatever is more constant.” The focus of this perek is the order in which the sacrifices must be brought in the Temple.

In any organization with operations as complex as those in the Temple there is a need to set a schedule and clear and consistent priorities. In the Temple there are many situations where the requirements of communal sacrifices are such that different korbanot must be brought, e.g. when Rosh Hashanah falls out on Shabbat and there are three separate “sacrifices of the day.” Even when dealing with sacrifices brought by individuals we may have situations where one person comes to the Temple with a number of different types of sacrifices, or several people come at once, bearing animals for different sacrifices. What is brought first, and what can wait until a later time?

The first Mishnah opens with the general statement that kol ha-tadir mehaveiro kodem et haveiro – whatever is more constant than another has precedence over another. That is to say that the more frequently a sacrifice is brought the greater its precedence in the order of korbanot.

While our perek deals with the question of which sacrifice takes precedence when two (or more) korbanot are to be brought, a different question arises when we need to bring a number of sacrifices and we do not have enough animals to satisfy all of the requirements. Should the special mussaf sacrifice be brought, or, perhaps, the animal should be saved for use as the “constant” daily offering? The discussion about this type of issue appears in Masechet Menachot (daf 49a) where the Gemara discusses a situation when there are not enough animals for both the temidim – the daily offerings – and musafim – the additional offerings on special days.

Zevachim 90a-b: Setting priorities in the Temple – II

As we learned on yesterday’s daf, the tenth perek of Masechet Zevachim focuses on issues of precedence regarding sacrifices. The first Mishnah in the perek taught that whatever sacrifice is brought on a more constant or consistent basis will be brought first. Thus, the korban tamid – the daily sacrifice – will be brought before a korban musaf – the additional sacrifice brought on Shabbat or holidays. The second Mishnah adds another rule – that whatever sacrifice is holier will be brought first. Thus, a korban chatat – a sin-offering – will be brought before a korban olah – a burnt offering, since the chatat offers atonement, and its blood is sprinkled in a more complete way on the altar.

The Gemara on today’s daf raises the question of what to do when these two sets of priorities come into conflict. Should the constant sacrifice be brought first or should the holier sacrifice be brought first?

The Gemara brings a number of proofs in an attempt to clarify this question. For example, on Shabbat the korban tamid is brought before the korban mussaf even though the korban mussaf is on a higher level of holiness (the korban mussaf is unique to Shabbat). Ultimately, the Gemara rejects this proof, as well as all of the other similar proofs, by arguing that on Shabbat even the korban tamid has enhanced holiness due to the fact that it is brought on Shabbat.

Since the Gemara does not come to any conclusion with regard to this question, the Rambam rules that in a case where two sacrifices stand before the kohen, one of which is brought on a more consistent basis and the other which is holier, the kohen can choose to bring whichever he prefers first (see Rambam, Mishnah Torah, Hilkhot Temidin U’Musafin 9:2).

Zevachim 91a-b: The frequency of circumcisions

As we learned on yesterday’s daf the Gemara is discussing how to deal with a situation where we find a conflict with regard to setting priorities in sacrifices. Should sacrifices that are brought on a more regular basis (tadir) be given priority or should the holier sacrifice (kadosh) be brought first?

One of the issues that the Gemara grapples with while discussing this question is how to define the term tadir, which we have translated as “constant,” that is to say, the sacrifice that is brought with greater frequency. The Gemara tries to bring a proof from the fact that a chatat (a sin-offering) and an asham (a guilt-offering) take precedence over a shelamim (a peace-offering), even though the shelamim was the sacrifice that was brought most often by people who accepted upon themselves the obligation to bring a korban. Rava objects to this proof, explaining that we must distinguish between tadir, which means “constant” and matzui, which means “common.” The fact that a korban is brought most often does not make it a constant obligation.

Rav Huna bar Yehuda questions Rava’s assertion by quoting a baraita that contrasts two positive commandments for which a person will receive the punishment of karet (a Heavenly punishment) if he neglects. The baraita states that the Passover sacrifice is not tadir, while the commandment of circumcision is tadir. In that case it does not appear that a circumcision is more constant that the korban Pesach, rather it is more common.

The Gemara’s answer is that the word tadir in the case of circumcision means tadir be-mitzvot.

Rashi explains this statement by the Gemara as referring to the idea that the commandment of circumcision contains many mitzvot. According to the Gemara in Masechet Nedarim (31b) the commandment of brit milah involves a thirteen-fold covenant – based on the fact that the word brit appears 13 times in Chapter 17 of Sefer Bereshit, where this commandment first appears. This raises brit milah to a higher level of importance. The Ohr Sameach offers an alternative approach, arguing that once a person is circumcised he remains in that state for his entire life and thereby lives in constant fulfillment of this mitzvah.

Zevachim 92a-b: Keeping the Temple vessels clean

According to the Torah (see Sefer Vayikra 6:20-21), in the context of discussing a korban chatat – a sin-offering – “Whatsoever shall touch the flesh thereof shall be holy; and when there is sprinkled of the blood upon any garment, thou shalt wash that whereon it was sprinkled in a holy place. But the earthen vessel wherein it is cooked shall be broken; and if it be cooked in a brazen vessel, it shall be scoured, and rinsed in water.”

Thus, if sacrificial blood is absorbed by another object, the laws pertaining to the sacrifice are transferred to the object unless the blood is removed. Specifically, clothing that was stained by blood had to be washed in the Temple courtyard, metal vessels that absorbed blood could be heated until the blood is removed, but earthenware vessels, which retain anything that they absorb, must be destroyed.

These laws are the focus of the eleventh perek of Masechet Zevachim, which begins on today’s daf.

Although the pesukim that serve as the source for this law deal specifically with a korban chatat, nevertheless the tradition accepted by the Sages is that the rule extends largely to all other sacrifices, as well. The Gemara examines which rules are limited just to the korban chatat and which apply to other situations. The first Mishnah teaches that this law is limited to blood that could be sprinkled on the altar. Thus, if the korban was disqualified for some reason, and the blood could not be sprinkled, or if it had been collected by someone who was unfit to participate in the sacrificial service (see above, daf 15) it also would not need to be cleaned from the priestly clothing. Similarly, if the sprinkling of the blood had already been done by the kohanim, the remnants of the blood would no longer require washing.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.