The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

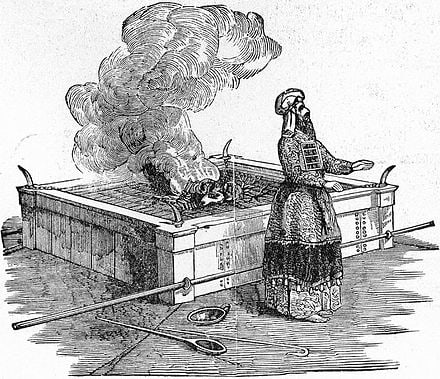

The Mishnah (22a) described the competition that took place on the ramp of the mizbe’ach in order to choose the kohen who would perform the terumat ha-deshen – cleaning ash from the altar – every morning. According to the Mishnah, the practice was abandoned in favor of a lottery system after one of the kohanim was pushed off the kevesh and was injured.

Our Gemara tells of an even more frightening story that was related to this competition. A baraita records that once two kohanim were racing up the ramp and one drew a knife and stabbed the other. When the father of the kohen who was stabbed came to his son, he found that he still had a breath of life in him and proclaimed “at least the knife did not become ritually defiled.” This story indicates the low level to which the priesthood had fallen towards the end of the second Temple period, that they were more concerned with the laws of ritual purity than the fact that someone had been murdered.

The baraita further records that a kohen named Rabbi Tzadok stood up and lectured the assembled people, comparing the murder that took place to a case of eglah arufah (see Devarim 21:1-9) – the ceremony that was done in a case where a dead body is found between two cities, and the murderer cannot be found. The leaders of both cities come as representatives of their respective cities to state that their city did all it could to protect this person, and to ask for atonement.

The Gemara points out that the case in the Temple was not truly analogous. In our case, the identity of the murderer was known, and the murder took place in Jerusalem, a city that is excluded from the regulations of eglah arufah. The Gemara explains that the purpose of the analogy was to make the people realize the severity of what had happened. As the Ritva explains, if in the case of eglah arufah, where it is not clear that anyone from the nearby city was responsible for the man’s death, nevertheless the city’s representatives had to accept a level of responsibility, in our case there is certainly a need for soul-searching after such a murder had taken place.

It appears that the Rabbi Tzadok of this story lived at the very end of the second Temple period, and is the same individual about whom the Gemara in Gittin relates that he fasted for 40 years in the hope that the Temple would be saved. The Gemara in Gittin also tells that one of Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai’s requests from the Emperor Vespasian was to send doctors to heal Rabbi Tzadok. Nevertheless, some identify Rabbi Tzadok as someone who lived in a much earlier period.

What parts of the Temple service are limited specifically to kohanim and forbidden to others? The Gemara on our daf brings a difference of opinion on the matter. According to Rav, there are four activities:

- Zerikah – Sprinkling the blood

- Haktarah – burning the incense

- Nisuch ha-mayim – pouring water on the altar on Sukkot

- Nisuch ha-yayin – the wine libation on the altar.

Levi accepts the position of Rav, and adds one more Temple activity as being limited to kohanim – Terumat HaDeshen – cleaning ash off of the mizbe’ach in the morning.

Several other activities in the Temple are mentioned as other possible avodah that is limited to kohanim. As an example, lighting the menorah, which the Gemara concludes is not an avodah. The Even Shlomo asks how the Gemara can come to this conclusion, given the repetition in the Torah that describes the lighting of the menorah as an activity done by the kohanim specifically (practically, it would be impossible for someone who is not a kohen to light the menorah, since its location in the kodesh (holy, inner part of the Temple) would not allow access to anyone who is not a kohen). The Li Le-yeshuah answers that when referring to hadlakat ha-menorah (lighting the menorah), the Torah is not only talking about lighting the menorah, but also all of the preparations, including cleaning out the remnants of yesterday’s flame and setting up the wicks for today’s lighting. These activities are certainly not avodah, nevertheless they are the responsibility of the kohanim and not of anyone else.

The Gemara does not come to a clear conclusion in the argument between Rav and Levi, as two baraitot are quoted each of which supports a different position. The Rambam in Hilkhot Bi’at Mikdash, rules like Rav, inasmuch as the prohibition against a non-kohen performing the service in the Temple is limited to a complete avodah, and not one that is only preparatory to others – like cleaning the altar.

The second Mishnah in this perek appears on our daf, and it discusses the second daily lottery, which determined which of the kohanim would slaughter the morning tamid sacrifice, who would sprinkle the blood, who would clean out the interior altar, who would clean out the menorah and who would place the various pieces of the butchered animal on the altar. In all 13 different kohanim received their assignments for the day as a result of this lottery.

The korban tamid was a korban olah, which was completely burned on the altar. As with all korbanot olah, after its slaughtering, the animal was divided up into large pieces, which were brought to the altar to be sacrificed. The details of how the animal was divided, which pieces were paired together, how they were carried to the mizbe’ach, etc. are not explained here, as that is the focus of Masechet Tamid.

The Mishnah does teach that the first parts of the animal that were brought to the altar were ha-rosh ve-ha-regel – the head and the legs. Rashi explains that the head is mainly bones, while the legs are mainly meat, so they complement each other while being sacrificed. The Me’iri, on the other hand, suggests that they are both mainly bones, and as such they are put together because of their similar nature. The Jerusalem Talmud explains that these two parts of the korban were brought to the altar together as the first parts to be sacrificed because as the animal walks it stretches its neck forward and lifts its legs to move. Thus it is sacrificed in the same manner in which it walked.

The description here in Masechet Yoma of the active participation of the kohanim in the daily procedure in the Temple acts as a contrast to the avodah of the kohen gadol on Yom Kippur, where he is the sole individual carrying out all of the avodah of that special day.

The Mishnayot on today’s daf focus on the number of kohanim needed to perform the various tasks that made up the daily Temple service. Obviously, any “special events” that were going on on a given day would affect the number of kohanim that were needed. The Mishnah teaches, for example, that the korban tamid, which was the first sacrifice brought every day, was brought by nine, ten, eleven or twelve kohanim, depending on the day.

The korban tamid itself needed nine kohanim. On Sukkot, when there also was a water libation, an extra kohen was needed to carry the jug of water.

The afternoon korban tamid needed eleven kohanim; the additional two kohanim carried extra wood to the altar.

On Shabbat there were eleven kohanim involved, two of whom carried the levona (frankincense) for the Lechem HaPanim (show bread). On Shabbat of Sukkot, there also was a kohen carrying the jug of water, so there were a maximum of twelve kohanim involved.

The Gemara teaches that the nisuch ha-mayim – the water libation on Sukkot – was only done with the morning tamid. As a proof to this a baraita is brought that recounts a fascinating story. As part of the avodah, the kohen who was to pour the water as part of the ceremony was instructed to raise his hand up so that it would be clear that he was doing the avodah properly. This was instituted because once a kohen poured the water on his feet instead of on the altar, and the enraged crowd pelted him with the etrogim that they were holding in their hands. The Gemara sees this as a proof that the nisukh ha-mayim was done in the morning, since the people were all carrying their etrogim.

The background to this story involves the different sects that lived during the second Temple period and their approaches to the Oral Law taught by the Sages. Many of the kohanim were Tzedukim, who did not accept the traditions of the Sages. Unlike nisuch ha-yayin – the wine libation – which is clearly written in the Torah, the nisuch ha-mayim – the water libation – was a tradition handed down from Moshe on Mount Sinai, and it was not accepted by the Tzedukim.

The particular story referred to in our Gemara, is described in great length in Josephus. According to him, the individual who poured the water on his feet rather than on the altar was Hasmonean king, Alexander Yannai, who rejected the teaching of the Sages. After the people – who supported the interpretation of the Sages – pelted him with etrogim, the king summoned the non-Jewish guard, and they killed many of the people who were on the Temple grounds.

We learned on daf 24 that there is a difference of opinion between Rav and Levi regarding the question of whether the Terumat HaDeshen could only be done by a kohen, which leads to a larger question – generally speaking, which parts of the Temple service had to be done by kohanim.

According to Rav, if a Temple activity

- that involved placing something on the altar, and

- was a complete avodah (i.e. nothing needing to be done afterwards)

was done by a non-kohen, he would be liable for death.

Levi disagreed, ruling that the Terumat HaDeshen – cleaning ash from the altar – was also forbidden to non-kohanim, even though it involved removing something from the altar, rather than placing something on the altar.

The Gemara on our daf introduces another part of the Temple routine and asks whether it falls into the category of activities that can only be done by kohanim – siddur ha-ma’arakhah – arranging wood on the mizbe’ach. Rabbi Assi quotes Rabbi Yochanan as ruling that it can only be done by a kohen.

The idea of siddur ha-ma’arakhah as an essential part of the service is derived by the Gemara from a passage in Vayikra 6:5, which is understood to be a command to the kohen the arrange the wood on the altar so that the first sacrifice of the day, the korban tamid, would be brought on the new day’s kindling wood.

In response is a question raised by Rabbi Zeira that arranging the wood is only the beginning of the process of the daily Temple service, so why should it be so severe as to be forbidden to non-kohanim on the threat of death?

The Gemara responds that Rabbi Yochanan considers it to be avodah tamah – a complete activity – since it concludes the preparations of the altar for the new day. On this point Rabbi Yochanan is in disagreement with Rav and Levi, who do not include this as one of the activities limited to kohanim, apparently because they see siddur ha-ma’arakhah as just the beginning of the avodat ha-yom (service of the day).

The third perek of Masechet Yoma begins on this daf. From here until the end of the Masechta, the unique Temple service of Yom Kippur is described, from the first tevilah (ritual immersion) of the kohen gadol, until he completes the avodah. This perek specifically is an introduction, as it discusses the preparations and special arrangements made for the avodah, without getting into the details of the avodah itself.

The first Mishnah in the perek describes how the appointed kohen would look to the east to watch for sunrise, which would allow for the beginning of the Yom Kippur service in the Temple. Upon sighting the sun, he would shout “Barkai!” The Mishnah continues by quoting Matya ben Shmuel who says that another question followed – “is the entire eastern horizon now lit up, all the way to Hevron?” This was necessary because of an error that had been made once, when the light from the moon fooled the kohanim and they began the avodah before the appropriate time, and the korban tamid (the first sacrifice of the day) had to be destroyed.

There are different opinions about the statement made by Matya ben Shmuel. According to the Rambam, Matya ben Shmuel was one of the tanna’im, and he was disagreeing with the first position in the Mishnah, arguing that the question presented in order to clarify that sunrise had occurred was whether it was light in the east all the way to Hebron. Tosafot Yeshanim argues that Matya ben Shmuel was the name of the kohen who was responsible for the lotteries that were done in the Temple (his name is mentioned in that context in Masechet Shekalim). If we accept this explanation, then he is not arguing, rather the Mishnah is describing that after the first sighting of the sun, Matya ben Shmuel followed by asking whether it was light all the way to Chevron.

The Meiri explains that Matya ben Shmuel’s question was whether the kohen watching for the sun could see all the way to Chevron in the south. In any case, the Jerusalem Talmud points out that everyone agrees that the reference was specifically to Chevron because they wanted to invoke the city where the forefathers of the Jewish people are buried.

The Mishnah (28a) taught that the kohanim were sent to search the skies on Yom Kippur morning in order to ascertain when the sun had risen and the Temple service could begin. The explanation for this procedure was that an error had once taken place and the light from the moon had been mistaken for the light of the sun.

In the course of discussing how this error could have taken place, the Gemara explains the difference between how the light of the sun is perceived, in contrast with the light of the moon, and concludes that only on a cloudy day could such a mistake have been made. This discussion leads the Gemara to quote a list of comparisons made by Rav Nachman. He begins with issues having to do with the sun – e.g. “sunlight diffused by the clouds is even stronger than direct sunlight” “the blinding sun that comes through a crack is more dangerous to the eyes than direct sunlight” – and then segues to other topics, such as “sinful thoughts are worse than sinful acts.”

The sin that is usually referred to by the Gemara when it uses the term aveira is a sin of a sexual nature. Thus, it appears that Rav Nachman is saying that forbidden sexual thoughts are worse than forbidden sexual acts, a statement that demands explanation.

Rashi explains that this does not refer to the severity of the sin, but to the lust that accompanies thinking about the sin, which is even greater than what exists during the sinful act itself. Nevertheless, most commentaries understand the statement to be referring to the severity of the thought and the act.

In the Moreh Nevuchim, the Rambam explains that the mind, the intellect, is on a much higher level than physical activities. Therefore, sinning in one’s thoughts creates greater damage to the person than does an act of sinning.

The Ohr ha-Chaim suggests that once someone has sinned, he has satisfied his inner need and is ready to begin a process of teshuvah – repentance – leading to atonement.

Sinful thoughts which are never acted upon, however, never satisfy the person, and he will never try to undo or repent from them.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.