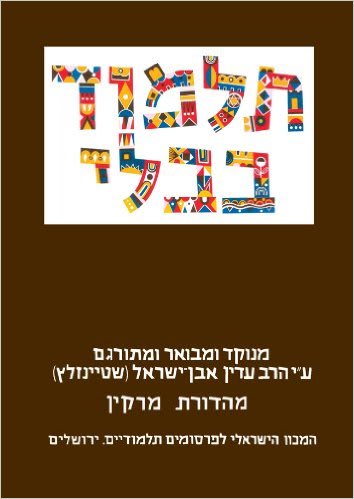

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Sotah 48a-b

Our Gemara describes the end of prophecy by stating that from the time that Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi died, clear prophecy no longer existed, although a bat kol – a heavenly voice – was still used.

The baraita offers two stories of bat kol use. In the first, the sages were gathered in the attic of Bet Guria in Yericho and a heavenly voice came out that said that among them sat an individual who was worthy of receiving prophecy, but he did not because the generation was not worthy. Those present understood that the reference was to Hillel HaZaken, a student of Ezra. In the second story the sages were gathered in an attic in Yavneh, and the heavenly voice again pointed to one of them as being worthy of prophecy, were it not for the undeserving generation. This time the reference was understood to be to Shmuel HaKatan, who was Hillel’s student.

The Talmud Yerushalmi brings other examples of a bat kol announcing information to the Jewish people. From our Gemara it is clear that the bat kol not only made statements, but also acted as the source for the information that the generation no longer merited true prophecy.

Gatherings of the sages in various attics – in the aliyah, or the second story of the houses at that time – are mentioned on many occasions throughout the Talmud. It appears that such meetings were arranged when the sages wanted to discuss a matter privately, or, perhaps, even secretly. One example is the decision to add a “leap month” to the calendar, something that was always done privately with specifically invited guests. Others are things that could not be discussed publicly because of political ramifications.

Shmuel HaKatan was one of the tanna’im who lived during the period of the destruction of the second Temple. The source for his title as ha-katan (the small one) is unclear. It may refer to his modesty, or, perhaps, to the claim that he was only slightly “smaller” – i.e. inferior – to the biblical Shmuel.

Sotah 49a-b

The closing Mishnah in Masechet Sotah teaches that historical events impacted on the day-to-day behavior of the Jewish community. Various tragedies led the sages to limit the festivities at weddings and even to change the educational curriculum, forbidding the study of chachma Yevanit – Greek wisdom.

The Gemara quotes a baraita that attributes the prohibition against studying Greek wisdom to the following story. After the death of Shlomtzion HaMalka who bequeathed her kingdom to her son Hyrcanus, his brother Aristoblus contested the decision and succeeded in ousting his elder brother. With the encouragement of Herod‘s father, Antipater, Hyrcanus gathered an army and attacked the city, forcing Aristobulus and his supporters to barricade themselves in Jerusalem. During this siege, which took place in 65 BCE, the Jews inside the city offered to purchase animals for daily sacrifices in the Temple in exchange for large sums of money.

The baraita relates that someone who was there who was knowledgeable in Greek wisdom hinted to the men outside the city that it was only the Temple service that kept Jerusalem from falling. The next day, in exchange for the coins that were sent down, instead of the promised sacrifice the soldiers sent back a pig, which reached out with its hooves halfway up the wall and caused the ground to shake. At that point the sages established an enactment forbidding the raising of pigs in Israel and teaching Greek wisdom to children.

This story appears in Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews 14:2), where it is related that the Jews inside the city offered 1000 drachmas for every Pesach sacrifice. The consequence of the story according to Josephus was a storm that destroyed almost all of the harvest in the land of Israel. Perhaps this incident is what the baraita means when it says that “the earth shook.”

Chachma Yevanit – Greek wisdom – does not appear to be secular knowledge generally, but rather refers to knowledge of Greek culture, music, literature, etc. Few people spoke classical Greek, and the story in our Gemara may indicate that the man “knowledgeable in Greek wisdom” was able to hint his intentions to others by presenting his message in a manner that only a select few could understand.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.