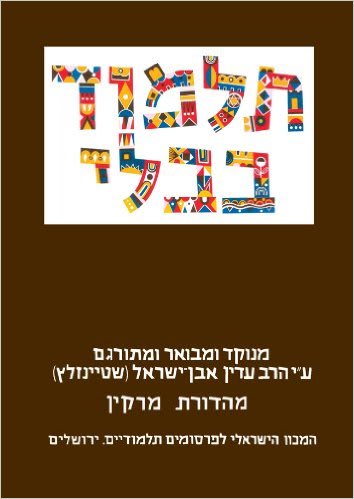

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Sotah 20a-b

According to the Mishnah on our daf, if the sotah is in fact guilty of adultery, after she drinks the “bitter waters” her face will begin to turn green and her eyes will bulge out. At that point the people standing nearby immediately remove her from the Temple precincts lest she metamei (ritually defile) the holy place.

The Gemara attempts to clarify what the fear of ritual defilement might be. It cannot be a concern that she will die since – at least on a biblical level – someone who is tameh met (one whose ritual defilement stems from contact with the dead) is permitted in the ezrat nashim – the area where she is given the “bitter waters.” Abayye explains that the concern is that she might bleed and become a niddah.

The Gemara offers support to the idea that a sudden fear might cause a woman to become a niddah from the passage in Megillat Esther (4:4), which is understood by Rav to mean that Esther became a niddah upon hearing that Mordechai was in sackcloth following Haman‘s decree. At the same time, the Gemara questions whether this is true, given the Mishnah in Masechet Niddah which teaches that fear stops a woman from menstruating. The Gemara’s explanation is that although a long-term fear may keep a woman from menstruating normally, a sudden shock may cause a woman to bleed.

A woman’s monthly menstrual cycle is dependent on hormonal activity which is directed by the brain. Severe emotional stress, like a long-term threatening situation, may cause regular menstruation to cease – even for an extended period – until the stressful situation has passed. At the same time, a sudden shock or severe emotional event may cause a woman to bleed outside of her normal cycle.

Sotah 21a-b

In the Mishnah (20a) Rabbi Yehoshua mentions a number of people who he categorizes as mevalei olam – those whose actions destroy the world. One of them is a chasid shoteh – a “foolish righteous person.” Our Gemara defines the term by giving the example of a man who sees a woman drowning and reacts by saying that, as a religious person, it is inappropriate for him to look at her – even though that is the only way to save her.

In his Mincha Charevah, Rav Pinchas Epstein asks why this person is considered a chasid shoteh; by allowing this woman to drown, he has transgressed the prohibition of lo ta’amod al dam re’ekhah (“do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor” – see Vayikra 19:16) and should be considered an evildoer. One possible answer is that there are other people in the vicinity who can step forward and save her, and he is considered a chasid shoteh since he does not hurry to fulfill this important mitzvah because of skewed priorities.

The definition of a chasid shoteh as offered by the Rambam is not only someone who refrains from performing mitzvot because of what he believes to be religious stringencies, but also someone who is overly concerned with stringencies in general (the example given by the Me’iri is someone who fasts on a daily basis). The Talmud Yerushalmi offers other examples to illustrate this concept, including someone who sees a child drowning and decides that he must remove his tefillin before jumping into the water to save him, someone who sees a potential rapist chasing after a young woman and is unwilling to strike out at the person, or even someone who sees a choice fruit on his tree and hurries to give it to charity without first making sure that the basic terumot and ma’asrot (tithes) have been taken properly.

Sotah 22a-b

On yesterday’s daf we learned about Rabbi Yehoshua‘s teaching in the Mishnah (20a) that a number of people are considered mevalei olam – those whose actions destroy the world. Makkot perushim is yet another example that Rabbi Yehoshua presents as mevalei olam. Our Gemara teaches that there are seven types of perushim that fall into this category, the common thread among them is that these people are hypocrites who present themselves as God-fearing, religious people when in fact they are just putting on a show.

The Gemara concludes with the advice that King Yannai offered his wife Shlomtzion before his passing. He told her that she should fear neither the perushim nor the Tzedukim, but rather she should fear the hypocrites who present themselves as though they are perushim, when in fact they are not. “Their actions are those of Zimri (see Bamidbar 25:14) but they expect to be rewarded like Pinchas (see Bamidbar 25:10-13).”

The perushim are the Pharisees, the sages of the Talmud, while the zedukim are the Sadducees, the elite class that rejected many of the traditions of the perushim. According to the Gemara, King Yannai was suggesting to his wife – who was to take the throne upon his passing – that although the he and the perushim had been enemies throughout his life, she had nothing to fear from them, since they would not hold his excesses and cruelty against her. Those who made use of their outward religiosity to hide their own desire for personal power were the dangerous ones.

This deathbed speech is recorded differently in Josephus (Book XIII, Chapter 15, number 5), where we find King Yannai telling his wife that she should run her affairs of state entirely according to the direction of the perushim. Historical evidence shows that she did so throughout her rule.

Sotah 23a-b

The Mishnah on our daf lists a number of differences between men and women with regard to a variety of issues of Jewish law. Among them are:

- When declared a metzora (biblical leper) a man must rend his clothing and loosen his hair (see Vayikra 13:45) while a woman does not.

- A man can accept upon himself his father’s nezirut, but a woman cannot (see the Gemara in Nazir 30a).

- A man can declare his son a nazir, but a woman cannot.

With regard to this last halacha, the Radak points out that the example of Hannah that appears in the Book of Shmuel would seem to stand in contradiction with the law of our Mishnah, for there we find that Shmuel‘s mother appears to successfully commit him to a life of nezirut (see I Shmuel 1:11). The Tiferet Yisrael on the Mishnah in Nazir (9:5) suggests that Hannah’s statement should not be understood as a full, complete neder (vow), but rather as a suggestion that she would encourage her husband to do so. In any case, it is difficult to see Hannah’s statement as a neder, given that it was made before the unborn child had even been conceived.

Moreover, it is not clear that Hannah’s statement referred to nezirut at all. In the last Mishnah in Masechet Nazir there is a disagreement as to whether the prophet Shmuel was actually a nazir. Rabbi Nehorai points to the prayer said by Shmuel’s mother, Hannah, prior to his birth where she promises u-morah lo ya’aleh al rosho (I Shmuel 1:11). He interprets this to mean that his hair will not be cut, similar to the statement made about Shimshon (see Shoftim 13:5), perhaps the most famous biblical nazir. Rabbi Yossi argues that morah simply means “fear” and that Hannah is saying that should he be born, her son will show no fear of man.

Most of the commentaries on Tanach, including the Septuagint, translate morah in our context as “metal” – that is to say, a razor. Targum Yonatan, however, suggests that the root of morah is marut – ownership or leadership.

Sotah 24a-b

The fourth perek of Masechet Sotah focuses on the question of whether the laws of Sotah apply to all couples. Among the cases presented in the first Mishnah (23b) is the case of an arusah – a woman who is engaged to her husband (i.e. she is considered married, having received kiddushin from him, but they have not completed the nisu’in and they have not had chuppah).

The Gemara brings a series of proof-texts to show the source of this halacha and suggests that the simplest source may be the tradition that Rabbi Aha bar Chanina brought “from the South” – that the passage mibaladei ishekh (see Bamidbar 5:20) teaches that the bitter waters of the sotah will only work if the woman has first slept with her husband before transgressing.

Rami bar Hama rejects this as a possible source, pointing to a case where the engaged couple had relations before their marriage. We see, therefore, that it is possible to have a case where an arusah will have slept with her husband before transgressing.

The Rambam teaches that the reason an engaged couple that had relations before completing their marriage cannot participate in the sotah ceremony is because the husband also committed a transgression when he had relations with his wife before their marriage was complete. The Ra’avad argues, claiming that this Gemara disproves the Rambam’s thesis, since it is clear according to Rami bar Hama that an arusah who slept with her husband would be eligible to drink the “bitter waters” were it not for other sources that forbid her from doing so.

With regard to Rabbi Aha bar Chanina bringing a tradition mi-daroma – “from the South” – apparently this is a reference to the period following the Bar Kochba revolt when the center of Jewish life moved northward to the Galilee. At that time, only a small number of Jewish communities remained in Judea and the southern part of Israel. These communities retained ancient oral traditions, and it is not unusual for the Gemara to report that a Sage returned from travel to the southern part of Israel with baraitot that were unknown to the Sages of the Galilee.

Sotah 25a-b

Our Gemara discusses the case of overet al dat – a woman who transgresses the Jewish code of ethics, asking whether she needs to be warned by her husband if he plans to divorce her without paying her ketubah. Can he simply divorce her, given her behavior, or must he warn her in order to give her the opportunity to rectify her behavior? After some discussion of the matter, the Gemara concludes that she needs to be warned.

The case of overet al dat is discussed at length in Masechet Ketubot (72b) where two different types of overet al dat are presented:

- Overet al dat Moshe

- Overet al dat Yehudit.

The case of overet al dat Moshe is one in which the woman transgresses a biblical law, and specifically, as explained by the rishonim, when her actions bring her husband to transgress as well. Examples include feeding him non-kosher food or engaging in relations with him when she is a niddah and forbidden to him.

The case of overet al dat Yehudit is where the woman engages in behaviors that are considered inappropriate for a Jewish married woman – for example, going out in public without a covering on her head.

The Gemara continues this discussion by asking whether a husband can choose to remain married to his wife even if she is overet al dat. Is the “Jewish code of ethics” objective, or does an individual husband have the ability to declare that these things do not disturb him? The conclusion of the Gemara is that overet al dat may be grounds for divorce, but a husband is not obligated to divorce his wife for these behaviors and can choose to remain married to her.

Although Rashi is viewed as limiting this discussion to the case of overet al dat Yehudit (in his opinion, were she to have been overet al dat Moshe and causing her husband to transgress biblical laws, there would be no need to warn her that she needs to change her behaviors), it appears that most of the rishonim understand the Gemara as applying to the case of overet al dat Moshe, as well.

Sotah 26a-b

One of the cases presented in the Mishnah (24a) of those who cannot become a sotah is the aylonit, who, according to the Tanna Kamma, will not be given the “bitter waters” to drink.

From the detailed discussions in the Gemara – mainly in Masechet Yevamot – it appears that an aylonit suffers from a genetic defect that does not allow her to have children. This is a different categorization than an akarah – a barren woman – whose physical and sexual development is ordinarily normal, but cannot have children because of some other deficiency or impediment. From those descriptions it appears that an aylonit can be recognized by certain unique physical traits, including a lack of secondary sex characteristics, like pubic hairs. Furthermore, it appears from the Gemara that there are different types of aylonit, ranging from women who have an overabundance of male hormones to those who suffer from Turner syndrome, where only one X chromosome is present and fully functioning. Approximately 98% of all fetuses with Turner syndrome spontaneously abort; the incidence of Turner syndrome in live female births is believed to be about 1 in 2500.

Within Jewish law there are many discussions about the status of an aylonit, mainly because of the lack of secondary female sex characteristics and because they develop at a relatively advanced age. Thus we find questions about when an aylonit is considered to have reached the age of adulthood, which halacha ordinarily defines as physical maturity.

From our Gemara, the exception of aylonit appears to be based on the fact that according to the Tanna Kamma a man is not permitted to marry an aylonit since she will not be able to bear him children. The Talmud Yerushalmi, however, suggests that the source for this law is the passage (Bamidbar 5:28) that promises that a sotah who is tested by the “bitter waters” and found innocent will become pregnant – a promise that applies only to women who can become pregnant.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.