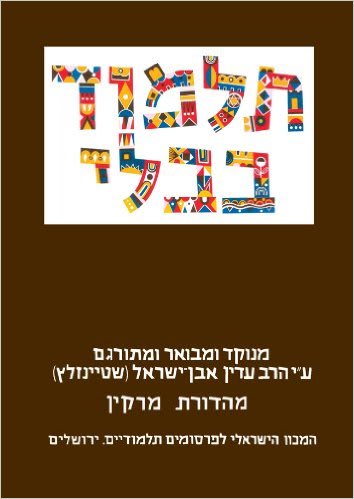

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, The Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Sotah 13a-b

Continuing the discussion of examples of middah ke-neged middah (measure for measure) in a positive sense, the Mishnah (9b) points to Yosef who personally took responsibility to bury his father (see Bereshit 50:7) and in turn had his own burial needs tended to by Moshe (see Shmot 13:19), who, in turn was buried by God, Himself (see Devarim 34:6).

Our Gemara discusses how in the midst of preparation for the Exodus, while the rest of the Jewish people were busy taking property from the Egyptians, Moshe chose to involve himself with the mitzvah of tending to Yosef’s bones, preparing to take them to Israel. It was, apparently, a difficult task to find Yosef’s remains, and the Gemara offers two explanations as to where they were. According to the first, he had been place by the Egyptians in a metal box and placed in the Nile so that its waters would be blessed by his presence. The second possible place is suggested by Rabbi Natan who says that he had been buried in the kabarnit shel melachim – apparently the burial cavern of the kings. In either case, the Gemara describes how Moshe called out to Yosef asking him to reveal himself in order to be taken for burial in Israel.

The Maharsha points out that according to the Midrashim, it was not only Yosef’s remains that were taken out of Egypt during the Exodus; all of the tribes took their forefathers’ remains with them. Nevertheless, only in Yosef’s case had the Egyptians taken an interest in burying him according to their traditions. Therefore, in all the other cases the place where the father of the tribe was buried was well known.

In fact, the Midrash offers an alternative reason to why Yosef had been placed in the Nile – that since the Egyptians knew that Yosef had made his brothers swear to take his remains with them to Israel (see Bereshit 50:25), they hid him in the hope that it would keep them from leaving.

Sotah 14a-b

Rabbi Hama bar Chanina taught that the passage commanding us to walk in tandem with God (Devarim 13:5) cannot be understood literally because God is an all-consuming fire (see Devarim 4:24). Rather we must understand this to mean that we should follow in the way of God, emulating His deeds.

For example –

- Just as God clothed the naked (Bereshit 3:21), so we should clothe the naked.

- Just as He visited the sick (Bereshit 18:1), we should visit the sick.

- Just as He comforted those in mourning (Bereshit 25:11), we should comfort those in mourning.

- Just as He buried the dead (Devarim 34:6), we should bury the dead.

The first example, which describes God as preparing “garments of skin” for Adam and Chava, is subject to a dispute between Rav and Shmuel, one of whom understands them as clothing made of skin, while the other defines them as clothing that is comfortable for the skin.

Rashi explains that the opinion which says “clothing made of skin” actually means that the clothing was made of wool, while the other opinion believes that it was made of linen. The Maharsha quotes the Chizkuni as pointing out that no animal had been killed at that time, so the clothing could not have been made of animal skins, and must be understood otherwise. Others argue that although Adam was not allowed to kill animals, there is no reason to think that he would not be allowed to make use of animals that had died.

In the midrashic literature there are a wide variety of opinions that offer different approaches to the essence of these garments.

The Maharal suggests that the dispute between Rav and Shmuel revolves around the question whether the purpose of these clothes was to cover their nakedness (i.e., for reasons of modesty) or for reasons of comfort.

Sotah 15a-b

The second perek of Masechet Sotah teaches about the preparations for the ceremony itself. The Mishnah on our daf teaches about how the “bitter waters” are prepared. The kohen would bring an earthenware peyale, and would fill it with a half log of water from the kiyor – the Temple washbasin. Rabbi Yehuda requires only a revi’it, one quarter of a log. Based on the passage in Bamidbar (5:17), dirt would be taken from the floor of the mishkan – or from under the stones of the Temple floor – to be placed in the water.

The peyale – or the Greek phiale – was a utensil used for cooking and drinking. The peyale could be made out of different materials, e.g. from earthenware or metal, and it was apparently shaped like a flat bowl (the Greek translation of the word ke–arah that appears as a utensil used in the mishkan is phiale).

One question that is raised about our Mishnah is why a Greek word is used to describe this utensil, rather than using a Hebrew word like kos (cup) or kedera (bowl). The Me’iri points out that the Targum of the expression kuba’at kos ha-tarela – “the cup of staggering” – in Yeshayahu (51:17) is, in fact, peyale, which hints to the cup from which the Sotah drinks, as well.

The word peyale is found many times in the Targum that originated in the Land of Israel as the translation of the word sefel (a bowl) – see, for example, Shoftim 5:25 in the Targum Yonatan.

Perhaps the simplest explanation of why the Mishnah chose to use this term is because it refers to a very specific type of utensil, which could not be expressed with the use of a generic term like “cup” or “bowl.”

Sotah 16a-b

As we learned on yesterday’s daf, the procedure for preparing the “bitter waters” involves mixing dirt from the floor of the mishkan or mikdash with the water that will be used. Our Gemara quotes a baraita that teaches that this is one of three cases where the same thing is seen –

- The dirt mixed with water in the case of Sotah

- The ashes mixed with water in the case of Parah Adumah

- The spit of a Yevamah during the chalitza ceremony.

Rabbi Yishma’el adds the case of the blood of the bird used in the ceremony marking the recovery of a metzorah (someone suffering from biblical leprosy) that is mixed with water.

With regard to this last case, Rabbi Yirmiyah asked Rabbi Zeira what to do if the bird is so large that the blood overwhelms the water so that no water can be seen, or if it is so small that the water overwhelms the blood and no blood can be seen. Rabbi Zeira’s response was “haven’t I told you not to remove yourself from the halacha?! The Rabbis were referring to a tzipor dror which does not grow so big or so small.”

We find quite a few questions in the Talmud raised by Rabbi Yirmiyah that relate to issues of limits on shiurim – the size requirements of the Halacha. These questions appear to lead to a possible conclusion that the shiurim cannot truly be significant since they cannot work in every single case. In many cases we find that Rabbi Zeira responds by saying that such questions should not be raised, since they are based on incorrect assumptions.

The tzipor dror that Rabbi Zeira mentioned is the passer domesticus or house sparrow, one of the most common birds, that lives wherever there is human habitation. Although they live in close proximity with humans, they have never been successfully domesticated – in the language of the Talmud (Beitzah 24a) einah mekabelet marut. They reach full growth (about 14 centimeters) in 2-3 weeks, although they continue to be raised by their parents for some time after that.

Sotah 17a-b

Our Gemara quotes a number of aggadic teachings in the name of Rava.

According to Rava, as a reward for Avraham’s statement (Bereshit 18:27) ve-anokhi afar va-efer – “who am I to argue with God; I am but dirt and ashes” – the Jewish people merited the mitzvot of Sotah (where the bitter waters are made from dirt taken from the floor of the mishkan) and Parah Adumah – the Red Heifer (which is made from ashes mixed with water).

In another statement, Rava taught that as a reward for Avraham’s statement (Bereshit 14:23) im mi-hut ve-ad serokh na’al – “I will take neither a string nor a shoe lace” – the Jewish people merited the mitzvot of Tefillin straps and the string of tekhelet on their tzitzit.

The Torah mentions the color tekhelet on many occasions, but it is not really a shade of color; rather it is the dye from which this color is made. Various discussions in the Gemara make it clear that the blue dye of the tekhelet was taken from a living creature called a chilazon. Because of the many Gemarot that describe the chilazon, it is difficult to identify one particular animal that meets all of the criteria, and there are many different opinions regarding its classification. The consensus of most opinions is that the chilazon is the snail “Murex trunculus” that is found on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea in the north of Israel. This creature has a unique liquid dye (that is not the animal’s blood), which, when mixed with other materials, produces the blue tekhelet color described in the Torah. Already during Talmudic times the use of tekhelet became a rarity, and within a short time its true source was forgotten.

It appears that the color of the tekhelet dye was a dark blue containing shades of green, which is why the sources compare it both to the sea and to grass.

Sotah 18a-b

We have learned that a woman whose husband has warned her of his concern regarding her behavior with a certain man will drink the “bitter waters” of a Sotah if she is seen having secluded herself with that individual. Our Gemara asks whether the woman can be put through this ordeal more than once. The position presented by Rabbi Yehudah is that a woman cannot be a judged as a Sotah more than once. He supports this with a story that once Nehunia Hofer Shihin testified before the court that a woman could be a Sotah more than once, but that his position was accepted only if she was married to a second husband, but not with the same husband.

According to the Mishnah in Shekalim (5:1) Nehunia Hofer Shihin – whose name literally means “Nehunia the ditch digger” – was one of the appointed workers in the Temple, whose official position was to be responsible for water for Jerusalem generally, and specifically for the pilgrims coming to the Temple during the holidays. The Gemara tells that Nechunia was an expert in choosing the correct place to dig wells, thus he was able to fill cisterns not only from the collection of rainwater, but from underground reservoirs, as well.

It appears that “the great cistern” referred to was one with which the Sages were familiar. In the Gemara in Yevamot (121b) a baraita is brought that tells the story of Nechunia Hofer Shihin’s daughter who fell into “the great cistern.” When the report reached Rabbi Chanina ben Dosa, he reported that all was well, and after a time that she had been saved. When questioned about it, Rabbi Chanina ben Dosa said that throughout the ordeal he was certain that Nechunia Hofer Shihin’s daughter was safe because she would not be punished with the very object that her father devoted his life to.

Sotah 19a-b

While the second perek of Masechet Sotah focused on the preparations that were done for the ceremony, the third perek, which begins on our daf, deals with the ceremony itself.

The first Mishnah in the perek teaches that the minha – the meal offering

– was removed from the basket and placed in a keli sharet – a utensil belonging to the Temple – and was given to the woman to hold. As is generally the case with menachot, tenufah – lifting the mincha – was then done, with the kohen placing his hands under the hands of the owner and lifting the mincha up in the air. Afterwards it was brought to the altar and sacrificed, with the remainder given to the kohanim to eat.

Tosafot bring a question that is presented by the Talmud Yerushalmi. Is there not a lack of propriety in having the kohen lift the mincha up thereby touching the hands of the woman? The Yerushalmi rejects the possibility that a cloth was placed between their hands, arguing that something like that would create a chatzitzah – a separation – which would not allow the requirement of tenufa to be fulfilled correctly. Rather, the Yerushalmi concludes, such a short term physical touch does not lend itself to sensuality.

Others suggest that the kohen did not actually place his hands directly under the woman’s while he was performing tenufa with her, rather he would hold the edges of the utensil on their upper end. The Tosafot ha-Rosh suggests that we can reconcile the two explanations by saying that the Talmud Yerushalmi recognized that given the close proximity of the kohen and the Sotah, it was likely that they would come into contact with one another, and that putting them into such a situation was deemed inappropriate. The conclusion, however, was that contact for just a moment is not something that should be of concern to us.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.