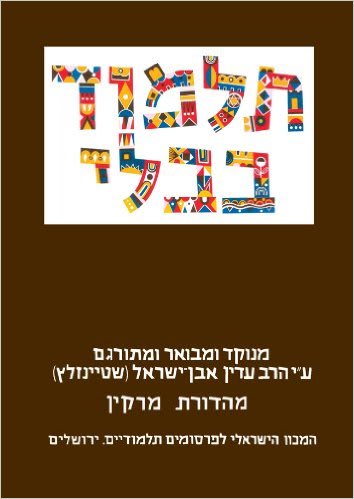

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Introduction – Masechet Avodah Zara

The prohibition against Avodah Zara – idol worship – is the most severe prohibition in the Torah. It includes the belief and worship of all deities whether on their own or in concert with God, whether they are perceived as spiritual, natural forces or animals. Any worship of these deities, whether worshiping the concept, the thing itself or a representative object, is forbidden as Avodah Zara. This prohibition appears in the Ten Commandments and is repeated throughout the Torah and the books of the prophets. In explanation of the severity of this act it must be understood that idol worship is the antithesis of the most basic Jewish concept, that is, the belief in a single, unique God who rules over all things. The Rabbinic statement that expresses this idea states “Whoever accepts Avodah Zara denies the entire Torah.”

Due to the severity of this prohibition, we find that the Torah commands us not only to refrain from idol worship, but also to destroy it and to stay away from it and from its adherents in a variety of different ways. Thus we are forbidden from following the ways of idol worshipers or attempting to appear like them (see, for example, Vayikra 18:3). The Sages added further limitations whose purpose is to discourage interaction with Avodah Zara and its followers.

Masechet Avodah Zara is found in Seder Nezikin as one of the tractates that follows Masechet Sanhedrin, and it expands on the ideas that are found there. While Masechet Sanhedrin focuses on the criminal aspects of Avodah Zara, the punishments for its worship, and so on, Masechet Avodah Zara deals with what is permissible and what is forbidden, under what circumstances, etc.

Another interesting aspect of Avodah Zara that is discussed in Masechet Sanhedrin is the fact that Avodah Zara is forbidden not only to Jews but to all people of the world, as it is one of the Seven Noachide laws. This impacts on Jews, as well, since they are commanded to destroy the idol worship in the land of Israel and, theoretically, throughout the world. Even if is not within the power of the Jewish people to accomplish this, nevertheless Jews are not allow to support those who want to worship idols or assist them in doing so.

As noted, the focus of Masechet Avodah Zara is on the need to remove oneself from idol worship and things connected with it. It is forbidden to derive benefit from the idols themselves, as well as their ornaments and donations made to them, and the Sages even decreed a severe level of ritual defilement for coming in contact with them. Similarly, participating in pagan holidays and festivals is forbidden. Much of Masechet Avodah Zara works at defining the boundaries of what would be forbidden, whether indirect benefit from Avodah Zara or passive participation in religious ceremonies would be permitted.

Part of the prohibition against benefitting from Avodah Zara forbids eating food that has been sacrificed as part of a pagan ritual. One aspect of these laws revolves around wine, and specifically yayin nesekh – wine that was libated on an altar to a deity. It was common practice for idol worshipers to pour off a small amount of wine to honor their deity before drinking. Such a libation would prohibit the wine, and the practice was so widespread that it was reasonable to assume that any wine that had been touched by a non-Jew had likely been poured off to a pagan deity. This led to the establishment of a Rabbinic injunction of stam yeinam – that even ordinary wine of non-Jews that had not been used for religious purposes was forbidden. This ruling was made both because of the concern with yayin nesech as well as because of a general interest in limiting the social interaction between Jews and pagans, as the Gemara teaches (Avodah Zara 36b) “The Sages decreed about their wine because of their daughters.”

Since Masechet Avodah Zara teaches about the need to remove oneself from idol worship and associated practices, it is necessary to describe the details of some of the common activities that were done as Avodah Zara. What we find in this tractate are mainly descriptions of Greco-Roman pagan practices as they expressed themselves in Israel and surrounding countries during the period of the Talmud. The Talmud anticipates that we will be able to reach conclusions regarding other pagan practices based on what we find here.

The teachings of the Torah focus on actual Avodah Zara, and into the times of the Mishnah and Gemara Jews found themselves living among people who practiced pagan religions. Over time, however, new religions developed whose basis is in Jewish belief – such as Christianity and Islam – which are based on belief in the Creator and whose adherents follow commandments that are similar to some Torah laws (see the uncensored Rambam in his Mishnah Torah, Hilkhot Melakhim 11:4). All of the rishonim agree that adherents of these religions are not idol worshippers and should not be treated as the pagans described in the Torah. Moslems certainly worship a single God and do not offer libations of wine. There are different approaches to Christians, where we find that the Rambam views them as basically pagans, while Tosafot – and even more so the Me’iri – view them as monotheists. Therefore, although many of the laws limiting interaction with non-Jews remain in place in order to avoid intermarriage and assimilation, other laws – e.g. limits on business dealings prior to their holidays – are assumed to be permitted. This is based on statements made in the Gemara that in the Diaspora it is impossible for Jews to avoid such interactions (Avodah Zara 7b) and that non-Jews living in Diaspora countries are not truly idol worshippers, they are just following the traditions of their fathers (Hullin 13b).

Avodah Zara 2a-b: Jewish merchants and pagan holidays

The Torah commands the Jewish people to remove themselves from interaction with pagan idol worship and from its adherents, so the reality of a Jewish population that lives in close proximity with non-Jews and interacts with them on a regular basis raises many questions. Given the centrality of idol worship to the daily life of a pagan, especially around certain holidays and places, the first perek of Masechet Avodah Zara discusses the need for Jews to avoid business interactions with these non-Jews around the time of their holidays.

The first Mishnah forbids engaging in business interactions – e.g., borrowing and lending – with pagans for three days before their holidays. Although this would appear to forbid both buying and selling, Tosafot and other rishonim quote Rabbeinu Tam as teaching that only selling would be forbidden, and even in the case of selling, only selling things that can be used in the course of worship cannot be sold.

The Gemara (6a) offers two reasons for this prohibition. One suggestion is that the non-Jew will be pleased with his purchase and will come to thank the pagan deity when the holiday comes about. Another suggestion is that by selling him something that will allow him to fulfill his worship, the Jew transgresses the prohibition of lifnei iver lo titen michshol – not to put a stumbling block before the blind. Since pagan idol worship is forbidden as one of the seven Noachide laws, it would be prohibited for a Jew to assist the non-Jew in performing this worship.

The Gemara does not reach a clear conclusion as to which of these reasons is primary. We find that Rashi quotes only the first reason – that the non-Jewish pagan will thank his god. The Me’iri and the Ritva, however, argue that the main reason is because of lifnei iver, and the other reason that is mentioned is taught only for a case where lifnei iver would not apply.

Avodah Zara 3a-b: Can non-Jews learn Torah?

According to the Gemara (2a) Rabbi Chanina bar Papa offered a homily suggesting that at the End of Days God will hold a Sefer Torah and announce that the ultimate reward will be given to those who involved themselves in Torah study. In this context the Gemara quotes the teaching of Rabbi Meir who teaches that a non-Jew who studies Torah should be treated like a kohen gadol – like the High Priest. This is based on the passage (Vayikra 18:5) that says that we must perform the laws of the Torah that a person does – asher ya’aseh otam ha-adam – and the terminology used is the generic ha-adam – “a person” – rather than Jewish people, like kohanim, levi’im and Yisraelim. Thus the credit given to someone who studies apparently applies even to non-Jews.

Tosafot note that according to the Gemara in Sanhedrin (59a) non-Jews are prohibited from learning Torah based on the passage (Devarim 33:4) Torah tziva lanu Moshe morasha – Moses commanded the Torah to us as an inheritance. The only exception would be the study of the seven Noachide laws, and Tosafot suggest that this must be Rabbi Meir’s intent. The Maharsha adds that we should not view the Torah that is permissible to non-Jews as being limited to those seven mitzvot. In fact, there are many Torah laws that apply to non-Jews aside from those seven that are emphasized because of their severity.

The Me’iri argues that Rabbi Me’ir is speaking about the entire Torah, and that the Gemara in Sanhedrin that forbids Torah study to non-Jews is limited only to those whose interest in learning Torah stems from curiosity or an academic interest in the subject. If, however, the non-Jew is searching for truth, which leads him to the Torah, or if he studies the Torah and fulfills it out of a sincere desire for a relationship with God, then this is not only permissible, but he is considered to be like the kohen gadol.

Avodah Zara 4a-b: Were the Talmudic Sages experts in the written Torah?

Were the Talmudic Sages experts in the written Torah?

The Gemara relates that Rabbi Abahu spoke highly of Rav Safra before a group of minim – sectarians – who arranged to free him from paying taxes for 13 years. One day they met Rav Safra and asked him to offer an interpretation of the passage in Sefer Amos (3:2) where it is taught that God favors the Jewish people, which is why he punishes them for their sins. Why would God take out His anger specifically against those whom he loves and favors?

Rav Safra could not answer their question, and they threw a scarf around his neck (either they were trying to choke him since he would not reveal the meaning, or else they took off his turban and threw it around his neck, embarrassing him). Rabbi Abahu came upon this scene and demanded an explanation. The minim said to him that they found that the man who Rabbi Abahu presented as a great person could not explain a passage in the Bible! Rabbi Abahu replied that he was great in his knowledge of the oral law, but not of the written Torah. He further explained that the Babylonian Sages spent all of their efforts studying the oral law, but since there were heretics in Israel who challenged the Sages with their interpretations of the Bible, the Sages in Israel needed to study the written Torah in order to respond to them. In closing Rabbi Abahu offered an explanation to the passage, that God takes out his anger slowly against the Jews, while against others he brings down a severe punishment all at once.

During Rabbi Abahu’s time – at the end of the 3rd century CE – groups of sectarians – especially Christians – began to come to positions of power in Israel, which is how they had the ability to influence tax collection on individuals. These sectarians focused on the study of Bible, which is why they were pleased to succeed in besting Rav Safra in a discussion of Biblical text.

Avodah Zara 5a-b: Different types of death

The Gemara on today’s daf suggests that the term “death” in the Torah may occasionally refer to other situations that bring one to be considered as dead. The four situations are:

- Oni – a poor person

- Suma – a blind person

- Metzorah – someone who suffers from Biblical leprosy

- Mi she’en lo banim – someone who is childless.

The Gemara offers support for each of these from Biblical passages.

Poverty:

After spending time exiled from his home, Moshe is told that he can return to Egypt since all of those who desired his life had died (Shemot 4:19). The Gemara identifies “those who desired his life” as Datan and Aviram (see Bamidbar chapter 16). This is consistent with the Sages’ identification of all unnamed enemies of Moshe – e.g. the two fighting Hebrews (see Shemot 2:13-15) – with these people. Although we know that they remained alive they apparently had lost their influence and ability to harm Moshe.

The Iyun Ya’akov teaches that we find the idea that poverty is worse than death in many sources, since it is ongoing, painful experience. The Maharsha explains that the passage brought in the Gemara that parallels the experience of poverty to that of Adam, based on the passage in Tehillim (82:7), is to be understood as follows: Just as Adam was condemned to suffer in this world (see Bereshit 3:19) similarly this individual will suffer oppression and poverty.

Blindness:

The passage in Eikhah (3:6) parallels blindness with death

Metzorah:

When Miriam, Moshe’s sister, is struck with leprosy, Aharon’s appeal to Moshe to pray on her behalf suggests that she is in a situation similar to death (see Bamidbar 12:12).

Childlessness:

When Rachel turns to Ya’akov and demands children, she insists that without children she will be considered as one who is dead (Bereshit 30:1).

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.