The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

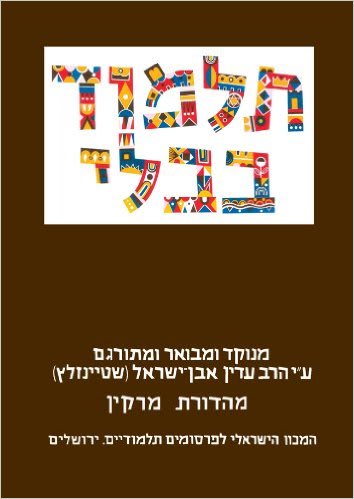

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Introduction to Masechet Sanhedrin

In contrast to its name, Masechet Sanhedrin is not solely focused on laws relating to the Jewish court system, rather it is the Tractate of the Jewish State. Masechet Sanhedrin deals with a broad range of issues that arise in connection with the workings of a Jewish State. All of the basic governmental institutions required by the Torah – and the relationships between them – are discussed in this tractate.

One of the basic foundational concepts of a Jewish State is the absolute rule of God as creator of the world. Much as God rules over the laws of nature, so He rules over the laws that obligate humankind. Only through God’s will do human beings have the ability to govern, an idea that is clarified in the words of the prophet Yeshayahu who says “For the LORD is our Judge, the LORD is our Lawgiver, the LORD is our King” (33:22). Thus, all of the different powers of government – legislative, executive and judicial – are listed as being under God’s authority.

In truth, there is no true legislative branch in the Jewish State, since all of the laws stem from the Torah itself. All later rules and regulations were established to clarify points of law that may not have been covered by the Torah or enactments made to protect the laws of the Torah. The true legislative branch is God Himself, or, more precisely, the laws of the Torah as a manifestation of His will. The Torah is the single source for the laws of the Jewish State, and so, God, its Author, remains the true Legislator forever.

In contrast, the judicial branch is entrusted to human beings, and specifically to the Sages of the Jewish people in every generation. It is the judicial branch that will interpret the eternal laws of the Torah so that they are appropriately applied according to the unique needs and realities of every generation. This power is given to a complicated set of courts, all under the supervision of the great Sanhedrin of 71 Sages that stands in the place of Moses and the 70 elders who joined him in judgment.

The executive branch of government in the Jewish State was the responsibility of the king – occasionally referred to as the “nasi” or president (see Vayikra 4:22 and Yechezkel 19:1 and 37:25) together with the ministers and officers that he appoints. The king was head of state, commander-in-chief of the military and responsible for both domestic and foreign policy — parallel to the role of many world leaders today. Regarding certain specific political questions that affected the entire nation — e.g. declaring war — the king was required to present his decision to the Sanhedrin for approval. Still, with regard to most areas of decision-making the king had complete rule and no other branch of government was involved.

The governmental structure described in Masechet Sanhedrin is not a utopian vision distant from reality. The government depicted is neither that of Messianic times nor of the age of the first monarchy under King David and King Solomon. Rather what we find described is the Jewish government of Mishnaic times. This is most clearly indicated by the concern shown for the roles of the king and the High Priest. The king in Masechet Sanhedrin is not from the Davidic dynasty and with regard to many laws he does not necessarily show full commitment to the rules of the Torah — it appears to be describing a king from the Hasmonean dynasty or from the kings that followed, e.g. King Herod.

From the time that the Jewish State lost its independence, Masechet Sanhedrin slowly lost its up-to-date significance. During the waning days of the Second Temple period the Sanhedrin decided to give up much of its authority so that it would not become an empty symbol of a theoretical power without any true sovereignty. Eventually the legal system described in this tractate became a description of an official structure that was no longer relevant, given that it had no authority while under foreign rule or in the Diaspora. Nevertheless, many of the laws that are discussed found application in various historical periods, and the basic conceptual foundation of this legal system has been used throughout the generations.

Having said this, it is important to emphasize that the laws of the Jewish State were never limited to the political boundaries of the state as they are understood today. The sphere of influence of the Sanhedrin and the authority of Jewish law extended to all Jewish communities. In every area where the Jewish community had autonomy that allowed it to apply Jewish law a local court was established that was subservient to the great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. Moreover, not only was the law system of the Jewish State not limited geographically, it did not limit itself solely to the rule of law. Jewish law includes ethical, community and religious law with no division between those laws that regulate interpersonal relations and those that govern relationships between man and God. Even those areas that are ordinarily seen as relating to community affairs — between man and his fellow man — include an element of concern with eradicating sin. In the view of the Jewish State, a sinful act impacts not only on the sinner but also on the community and the land of Israel itself.

Thus, the rules and regulations of Jewish law do not merely serve as tools to create an orderly society, rather their purpose is to create a Godly community, to build a state whose purpose is to serve God in every aspect of society.

Understanding this helps explain basic differences between the Jewish court system and the secular one, both in terms of goals and in terms of application of the law. The Torah refers to a judge sitting in judgment as elohim (see Shemot 21:6 and 22:8), indicating that he is involved in holy work – in God’s work. As such, it is incumbent on the judge to reach a conclusion that is not dependent on human assumptions — one that leaves no room for doubt — and wherever the evidence leaves unanswered questions, the accused will be set free.

For this reason, it is not enough for the judge to be a scholar and an expert in jurisprudence. He must also have semikha – ordination unlike what exists today – that is, receiving a charge from a teacher who received it in a direct chain of transmission from Moshe Rabbeinu. This semikha not only acts as official permission to judge, but it also offers some level of a heavenly promise that there will be a Godly presence in the courtroom. It is this level of divine intervention that leads to a command to accept the ruling of the Sanhedrin – see Devarim 17:11.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.