The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Among the various practices that the Gemara on today’s daf (=page) recommends to judges, Rabbi Eliezer teaches that a judge should avoid “stepping on people’s heads.” The source that he brings is the juxtaposition of the two biblical passages forbidding climbing stairs up to the altar and commanding that laws be placed before the Jewish people (see Shemot 20:22 and 27:1).

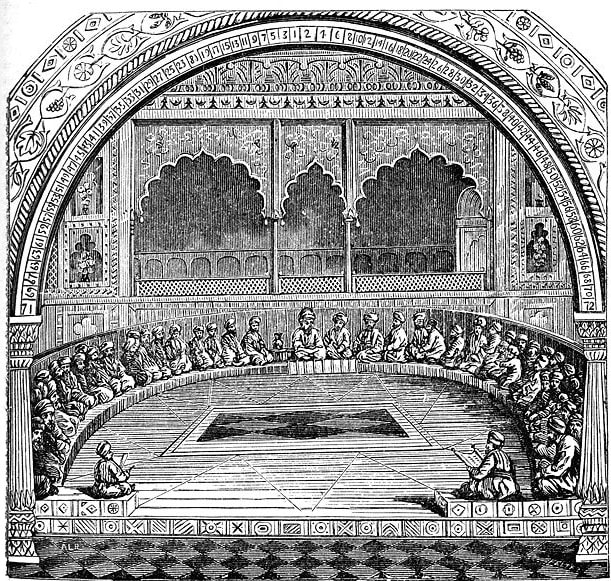

This description is based on the way the students sat in the academies during the time of the Mishnah and Gemara. The lecturer or the head of the yeshiva would sit on the floor facing the students, who would be sitting facing him in a series of rows. Ordinarily people had assigned spots based on their seniority, with the more learned and experienced students sitting in front, closer to the Sage. Were one of the students whose spot was near the front to arrive late, after all of the other students were already seated, he would need to “step on the heads” of the other students in order to get to his place.

The Gemara in Yevamot (105b) describes such an incident.

The Gemara relates that Rabbi Chiya and Rabbi Shimon the son of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi were discussing whether a person should look upwards during prayer (based on the passage in Eicha 3:41) or downwards (based on the passage in I Melakhim 9:3). Rabbi Yishmael the son of Rabbi Yossi overheard their discussion and shared his father’s teaching – that a person should look upwards but direct his heart downwards in order to fulfill both passages.

As they were talking, Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi entered and the students – who sat in assigned places on the floor during the lecture – all hurried to find their seats. Rabbi Yishmael the son of Rabbi Yossi was heavy-set and was unable to reach his place easily, so he appeared to be “walking on people’s heads” as he made his way to his seat. The Gemara then records an exchange between Rabbi Yishmael the son of Rabbi Yossi and Avdan, one of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s students, where Avdan reprimanded Rabbi Yishmael for “stepping on people’s heads,” but Rabbi Yishmael successfully defended his actions.

Our Gemara continues with a number of rules and regulations that the judges and courts must follow based on the instructions given by Moshe as described in the beginning of Sefer Devarim.

The Torah teaches lo takiru panim b’mishpat (Devarim 1:17) – literally “do not recognize faces in judgment.” Rabbi Yehuda understands this to mean that when in court, the judge cannot show favoritism to someone with whom he is friendly. Rabbi Elazar suggests that it means that the judge must treat someone who he does not like as if he does not know him.

To illustrate this rule, the Gemara tells of Rav’s tenant who came to him on a legal matter and asked him to act as a judge. Rav argues that that relationship did not allow him to act as judge, and he asked Rav Kahane to play that role. Rav Kahane saw that the tenant was behaving as though he would receive preferred treatment given his relationship with Rav, and he rebuked him saying “if you listen, good and if not I will take Rav out of your ear!”

This odd statement is understood by most commentaries as meaning that he will make the tenant forget Rav by making it clear that Rav would not be helpful to him in any way.

In another case, Reish Lakish quotes the passage in Devarim (1:17) as obligating the judges to take up the case of a single prutah with the same interest that is devoted to a case of one hundred maneh. The Gemara objects that this is obvious, and concludes that the intention is to obligate the courts to accept cases as they come and not to deal with more prestigious cases before simpler cases.

A prutah is the smallest coin that was in use in the time of the Mishnah; a single dinar contained 192 perutot, and a maneh contained 100 dinarim. As such, the 100 maneh mentioned by Reish Lakish is about two million perutot.

Generally speaking, halacha does not allow a person to incriminate themselves.

Based on this rule Rav Yosef teaches that if someone makes a statement that will incriminate him the court will reject the statement in its entirety.

The opinion is presented in the name of Rava that adam karov etzel atzmo, ve-ein adam masim atzmo rasha — just as a person cannot testify against a close relative in bet din similarly he cannot testify against himself, incriminating himself. Nevertheless, as the continuation of the Gemara concludes, there exists an often discussed Talmudic idea — palginan diburei — that we split up his statement between what he says about himself, which we do not accept, and what he says about others, which we accept as testimony. For example, if a person says “I killed someone” we reject his self-incriminating statement, but we accept his testimony that the man had actually been killed.

The mechanism behind the concept of palginan diburei is subject to a disagreement among the rishonim. The Rashba argues that we can only apply it in cases where we can interpret the testimony in a way that will allow his entire statement to be understood as being truthful. For example, in the case mentioned above, we could say that the witness who says “I killed him” actually means “I killed him…accidentally.” If it is impossible to interpret his testimony in such a way, we would not apply the principle of palginan diburei, and we would reject his testimony entirely. Others, however, explain that the concept of palginan diburei is powerful enough to allow us to accept the conclusion of his testimony (that the man is dead) even as we reject the incriminating aspect of it (that the witness murdered him).

It should be noted that the rule ein adam masim atzmo rasha applies only in cases of criminal acts that would lead to punishments such as lashes or a death penalty. If someone admits to owing money then the court will view his confession as equivalent to testimony made by witnesses, and obligate him to pay.

As we learned in the first Mishnah in Masechet Sanhedrin, different courts were established to deal with different types of cases, with courts of three, 23 or 71 depending on the case. One situation where we find a disagreement relates to ibur shana – establishing a leap year in the Jewish calendar. When discussing ibur shana, Rabbi Meir rules that a court of three judges suffices; according to Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel they begin with three, continue the discussion with five and conclude with seven judges. Nevertheless, if the decision was made with three judges it will also suffice.

While the commonly used calendar – the Gregorian calendar – is a solar calendar that reflects the relationship between the earth and the sun (a single revolution of the earth around the sun – just over 365 days – is considered a year), and the Muslim calendar reflects the relationship between the earth and the moon (a single revolution of the moon around the earth – about 29 days – is considered a month), the Jewish calendar combines the two by establishing lunar months that must coincide with the solar year.

A leap year in the Jewish calendar involves the addition of an extra month, which serves to keep the lunar calendar in sync with the solar calendar. The court must decide – based on whether the Passover holiday will occur in the Spring, as required by the Torah (see Devarim 16:1), together with other factors – when to add the extra month.

It should be noted that in our present situation, with neither an operating Sanhedrin nor the ability of a single group of Sages to represent the Jewish People, we rely on a set calendar established by Hillel the Second, which is based on astronomical calculations. According to the set calendar, the extra month is inserted seven times every 19 years.

Our Gemara describes the end of prophecy by stating that from the time that Chagai, Zechariah and Malachi died, clear prophecy no longer existed, although a bat kol — a heavenly voice — was still used.

The baraita offers two stories of bat kol use. In the first, the sages were gathered in the attic of Bet Guria in Yericho and a heavenly voice came out that said that among them sat an individual who was worthy of receiving prophecy, but he did not because the generation was not worthy. Those present understood that the reference was to Hillel ha-Zaken, a student of Ezra. In the second story the sages were gathered in an attic in Yavneh, and the heavenly voice again pointed to one of them as being worthy of prophecy, were it not for the undeserving generation. This time the reference was understood to be to Shmuel HaKatan, who was Hillel’s student.

The Talmud Yerushalmi brings other examples of a bat kol announcing information to the Jewish people. From our Gemara it is clear that the bat kol not only made statements, but also acted as the source for the information that the generation no longer merited true prophecy.

Gatherings of the sages in various attics — in the aliyah, or the second story of the houses at that time — are mentioned on many occasions throughout the Talmud. It appears that such meetings were arranged when the sages wanted to discuss a matter privately, or, perhaps, even secretly. One example is the decision to add a “leap month” to the calendar, something that was always done privately with specifically invited guests. Others are things that could not be discussed publicly because of political ramifications.

Shmuel HaKatan was one of the tannaim who lived during the period of the destruction of the second Temple. The source for his title as HaKatan (the small one) is unclear. It may refer to his modesty, or, perhaps, to the claim that he was only slightly “smaller” — i.e. inferior — to the biblical Shmuel.

As we learned above (see daf, or page 10), one of the important responsibilities of the Jewish court in Israel was to establish leap years in order to keep the Jewish calendar in sync with the solar calendar. The Gemara on our daf describes how messages were sent between Israel and Bavel under Roman rule when the persecutions of the Jews reached such a height that, as in the days of Hadrian, all religious exercises, including the computation of the calendar, were forbidden under pain of severe punishment. The messages were sent in an obscure form to prevent them from being stopped by the Government under the reign of Constantius II (337-361 C.E.).

Rava received the following message:

A pair [of scholars] came from Rakkat [that is, Teverya, whose biblical name was Rakkat, where the Sanhedrin was operating at that time] and they were captured by an eagle [i.e. by Roman soldiers, whose symbol was an eagle]. In the hands of the messengers were things made in Luz, that is purple [apparently, aside from their message they were also transporting tekhelet for the religious needs of the Jewish community in Bavel]. Yet through Divine mercy and their own merits they escaped safely [and were not put to death — yet they were unsuccessful in sharing the information with the Jewish community in the Diaspora].

Several explanations are offered to explain the eagle – the nesher – that kept these messengers from fulfilling their mission. It could refer to the Roman Caesar, or king, as in Yechezkel 17, although the Ramah suggests that it is a reference to bandits who preyed on travelers going through the forests. We know that the eagle was one of the primary symbols of Roman rule that appeared on the staff carried together with every Roman legion. Such “eagles” were much more than flags; they became an icon for that particular legion, and ultimately the symbol of the Roman army.

According to the Mishnah, among the ceremonies that require the participation of three judges is semichat zekeinim – rabbinic ordination.

In searching for a source for this requirement, Abayye points out a difficulty – if the source is the passage (Bamidbar 27:23) where Moshe lays his hands on Yehoshua to declare him his successor, then it would appear that a single judge would suffice. And if we saw that Moshe embodies the Sanhedrin and is considered the equivalent of its 71 members, then we should need a full Sanhedrin to confer rabbinic ordination.

Although the Gemara does not offer a response to that question, some suggest that there must have been others standing together with Moshe who are not mentioned because of the great honor given to Moshe. This answer is based on the continuation of the Gemara that describes a unique situation of semichat zekeinim.

Rav Yehuda quotes Rav as telling about Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava who must be remembered for keeping the laws of kenasot — penalties — from being forgotten. The Gemara explains that under Hadrian the Roman government forbade the conferring of rabbinic ordination. They announced that anyone giving or receiving ordination would be killed and nearby cities and provinces would be destroyed and uprooted. Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava gathered five students to a place midway between large cities and mountains and conferred rabbinic ordination on Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehuda, Rabbi Shimon, Rabbi Yossi and Rabbi Elazar ben Shamua. While he was killed for his efforts, his students survived to act as teachers and judges.

In this case the Gemara explains that he had other partners in this act, but they are not mentioned due to the honor that they wanted to give to Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava. Many rishonim believe that only one of the three people giving semikha needs to have ordination himself, in which case Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava did not need other people as he could have had his students participate in granting ordination to their friends, and then have them switch positions to confer ordination on the rest of the group.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.