The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Menachot 65a-b: Harvesting the new barley crop

The Mishna on today’s daf describes how the barley was harvested and prepared for the korban ha-omer brought on the second day of the Passover holiday –

The messengers of the bet din used to go out on the day before the festival and tie the unreaped barley in bunches to make it the easier to reap. All the inhabitants of the nearby towns assembled there, so that it might be harvest would be done with much publicity. As soon as it became dark the reaper called out:

- ‘Has the sun set?’ and they answered: ‘Yes!’

- ‘Has the sun set?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- ‘With this sickle?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- ‘With this sickle?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- ‘Into this basket?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- ‘Into this basket?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- On Shabbat he called out further:

- ‘On this Shabbat?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- ‘On this Shabbat?’ and they answered, ‘Yes!’

- ‘Shall I reap?’ and they answered, ‘Reap!’

- ‘Shall I reap?’ and they answered, ‘Reap!’

- He repeated every matter three times, and they answered, ‘Yes!’ ‘Yes!’ ‘Yes!’

- And why was all this?

- Because of the Baitusim who maintained that the reaping of the omer was not to take place at the conclusion of the first day of the festival.

The Gemara explains that the Baitusim were a religious sect that disagreed with the tradition of the Sages regarding the korban ha-omer. The Sages interpreted the passage in Sefer Vayikra 23:11 that says that the omer must be brought on the day following “Shabbat,” as referring to the first day of the Passover holiday. The Baitusim argued that the korban ha-omer was always brought on Sunday, so that Shavuot could only fall out on Sunday, as well.

The Gemara records that when the Sages succeeded in instituting an accepted practice that clarified the halacha and placed Shavuot in its proper time according to their tradition, a minor holiday was established and recorded in Megillat Ta’anit.

Megillat Ta’anit is a little known collection of statements about minor holidays and fasts that commemorate events which took place during the Second Temple – although there are also events from earlier and later periods included, as well. This work is set up chronologically, and it includes the date and a brief account of the incident written in Aramaic, followed by a fuller description of the event in Hebrew. (Although it is not part of the standard texts of Talmud, the Steinsaltz Talmud includes it as an addendum to the volume that contains Masechet Ta’anit).

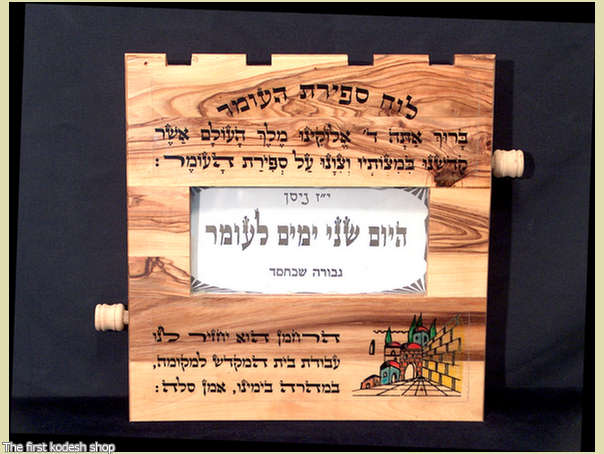

Menachot 66a-b: Counting the Omer

The Torah commands that we count the fifty days from the holiday of Pesach until Shavuot (see Sefer Vayikra 23:15-16), a tradition that is kept to this day, even though the associated sacrifices can no longer be brought. The first of those pesukim discusses counting seven weeks, while the second discusses counting 50 days. Abayye concludes that there is a distinct commandment to count the days as well as a second commandment to count the weeks.

The Gemara relates that the Sages of Rav Ashi‘s study hall counted both days and weeks, while Amemar only counted days without counting weeks. He explained that after the destruction of the Temple counting was merely zecher le-Mikdash – in memory of the Temple practice – so a partial counting was sufficient.

With regard to the basic requirement to count both days and weeks, the Rambam suggests that nevertheless there is still just a single mitzvah of counting, although Rabbeinu Yerucham argues that they are two separate mitzvot so that when the Temple stood two separate blessings were made on their performance. It appears that the basic requirement is to summarize the conclusion of each seven days with the words “…that are a single week in the omer,” or “…that are two weeks in the omer,” and so forth. Nevertheless it is common practice today to include both the number of weeks and days in every counting after the first seven days are completed.

Tosafot bring the opinion of the Ba’al Halachot Gedolot who ruled that someone who missed a day of counting can no longer count, and questioned why this should be true. The Rosh explains that since counting every day is a mitzvah there is no reason to think that missing one day should preclude fulfilling the commandment of counting on the rest of the days. Some answer that according to the Behag the mitzvah is the full counting, and the daily blessing is on the partial fulfillment of the commandment. In fact, the accepted halacha is that if someone misses a single day he should continue counting, although he no longer can recite a blessing on the remaining days.

Menachot 67a-b: The availability of new grain in the marketplace

According to the Torah, until the omer offering was brought on the second day of Pesach, the new grain harvest could not be consumed (see Vayikra 23:14). The Mishna on today’s daf records that once the korban ha-omer was brought, one could enter the Jerusalem marketplace and immediately find that flour from the new harvest was available for purchase. Rabbi Meir says that this situation existed against the wishes of the Sages; Rabbi Yehuda says that it was done with the permission of the Sages.

The rishonim disagree about what the Sages may have found to be objectionable. Rabbeinu Gershom explains that the Sages were concerned with the fact that the harvest took place before the omer was harvested and brought to the Temple, lest people come to partake of the new grain before the proper time. In his Commentary to the Mishna, the Rambam explains that there was nothing untoward with the harvest, the concern was with the ready availability in the marketplace even before the offering had been brought.

The Gemara asks why Rabbi Yehuda does not appear to be concerned lest people eat from the new crop while it is still forbidden, since we find that on the day before Passover he permits searching for hametz only when it can still be eaten; once it is forbidden to eat he becomes concerned lest a person eat it accidentally should he find it.

While both Abayye and Rava offer suggestions in the Gemara explaining why Rabbi Yehuda may be inclined to show concern about eating chametz after the time that it becomes forbidden, even though he is not worried about eating new grain before it becomes permitted, in his Netivot ha-Kodesh Rabbi Avraham Moshe Salman offers a simple distinction. When a forbidden food is a simple lav – a negative commandment – Rabbi Yehuda is not concerned lest it be eaten accidentally. Chametz on Pesach, however, which carries with it the severe punishment of karet, demands a more restrictive Rabbinic prohibition.

Menachot 68a-b: Permitting the new harvest

When the Torah teaches that it is forbidden to eat grain from the new harvest (see Vayikra 23:14), it appears to offer two separate mechanisms for permitting the new crop. According to the Torah “…neither bread, nor parched corn, nor fresh ears” can be eaten –

- until this selfsame day,

- until you have brought the offering of your God.

Thus it appears that the arrival of the day itself permits the new harvest, yet there is also the element of waiting until after the korban ha-omer is brought.

Rav and Shmuel both explain the passage as follows. When the Temple stood and the omer offering was brought on the second day of Pesach (the 16th day of Nissan), the new crop became permitted only after the korban ha-omer. Following the destruction of the Temple, the dawn of the 16th day of Nissan permitted the new crop to be eaten.

According to the Mishna, during the time of the Temple, Jews who were far from the Temple could assume that by mid-day the korban ha-omer would have been brought, and they were permitted to begin eating from the new crop. Following the destruction of the Temple, Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai established a rule that forbade eating from the new crop until the morning of the 17th day of Nissan. His reasoning was that when the Temple is rebuilt – speedily in our days! – people would mistakenly think that they can begin eating from the new grain on the morning of the 16th, not realizing that they were only permitted to do so in the past because no korban ha-omer could be brought. In order to keep them from that mistake, he did not permit the new harvest until the following day.

Rabbi Yochanan and Reish Lakish disagree with Rav and Shmuel, arguing that even when the Temple stood the new crop became permitted with sunrise on the 16th of Nissan. Nevertheless there was a special mitzvah to wait until after the korban ha-omer was brought before beginning to eat.

Menachot 69a-b: Utensils that can – and cannot – become ritually defiled

Ritual defilement of utensils is a topic to which an entire tractate of Mishnayot – Masechet Keilim – is devoted. In a number of places the Torah teaches the laws of utensils that come into contact with dead creatures and become tamei (defiled). For example, in Sefer Vayikra (11:29-35) the Torah lists different types of animals that defile upon their death, and includes the kinds of utensils that can become defiled. Similarly, in Sefer Bamidbar (31:20-23) in the context of the booty captured by the Children of Israel in their war with the Midianites, we learn of different materials that will become tamei and must be purified for use. Generally speaking, there are seven types of utensils that fit this category: If they are made of metal, wood, animal skin, bone, cloth, sack or pottery. In addition, glass utensils can become tamei on a Rabbinic level.

The Gemara on today’s daf teaches that there are some types of utensils that do not become ritually defiled, neither on a Biblical nor on a Rabbinic level. These are klei avanim, klei gelalim and klei adama, which retain their “earthiness” and are not considered to be full-fledged utensils that would render them important enough to become tamei.

Klei avanim are stone utensils. Klei adama are utensils made from earth. Some explain that they are made from stones that have been sanded down, others suggest that they are earthenware that never was placed in a furnace to be finished. Klei gelalim may be made from a large stone that can only be moved by rolling; others suggest that these are made from animal excrement.

In this context the Gemara brings a question posed by Rami bar Hama – if an elephant swallows a kefifah Mitzrit – a basket woven from Egyptian reeds – and excretes it whole, is it considered klei gelalim to the extent that it would no longer be considered tamei? While the Gemara rejects this possibility, it does consider whether if the elephant ate the reeds themselves and then excretes them that they may be considered gelalim so that a basket made from them would be considered klei gelalim.

A kefifah Mitzrit is made from soft palm branches specifically because it remains flexible even as it retains its shape. Such a basket could, theoretically, be swallowed by a large animal and return to its original shape after being eaten.

Menachot 70a-b: Does Jewish law consider rice to be a type of grain?

The Mishnayot in this perek have been discussing the laws of chadash – the new grains that are permitted only after the second day of Passover. The Mishna on today’s daf enumerates the types of grain that fall into this category – wheat, rye, oats, barley and spelt – all of which are also obligated in the mitzvah of hallah.

In the Gemara Resh Lakish explains that the Mishna specifically comes to exclude orez – rice (oryza sative) – and dochen – millet (panicum miliaceum). He derives this from the parallel between the commandment to separate challah when eating lechem (see Bamidbar 15:19-21), and the commandment to eat matzah – lechem oni – for it is specifically from these types of grains that matzah can be made. The Gemara learns this from the passage (Devarim 16:3) that forbids the eating of chametz in the same context as the command to eat matzah, connecting the two to one-another.

Although our Gemara takes for granted that rice is not considered a type of grain, this is subject to a dispute between the Sages of the Mishna in Masechet Pesachim (daf 35a), where we find that Rabbi Yochanan ben Nuri rules that rice is also a type of grain for which one would be held liable for eating if it became chametz, and that one could fulfill the mitzvah by baking it into matzah.

The accepted opinion understands that the process of mixing rice with water does not lead to chimutz – fermentation – but to sirhon – spoilage. The Jerusalem Talmud explains that establishing which types of grains are those that can become chametz and matzah was based on extensive research done by the sages, who experimented with the baking process to ascertain whether the fermentation process takes place. With regard to a small number of grain-type products, there remained differences of opinions as to whether the process that took place should be considered chimutz.

Menachot 71a-b: Farming dispensations

According to the Mishna on today’s daf there were places where reaping the new crop was permitted even before the korban ha-omer that permitted the new harvest was brought on Passover. In irrigated fields found in the valleys early harvest was permitted, either because the heat in those places led the grain to ripen early, and it would become ruined if it was not harvested, or because what grew in these places was low quality and the Sages’ injunction against harvest did not apply to them.

The Mishna relates that in the city of Yericho the farmers followed this policy and harvested early with Rabbinic approval; nevertheless when they stacked the harvested grain it was done without the approval of the Sages, who, nonetheless, did not stop them from doing so.

Yeriho is located in the Jordan Valley, one of the lowest places in Israel (and, indeed, in the entire world). Its fields were irrigated from ancient fresh water springs as well as from the Jordan River itself.

The Gemara relates a number of other activities done by the people of Yericho, some of which were approved of – or at least accepted by – the Sages, others of which the Sages objected to. Among the activities that were done with Rabbinic approval was markivin dekalim kol ha-yom – that the farmers “grafted” palm-trees the entire day of the 14th of Nissan, even though traditionally people did not work on the day before the Passover holiday.

The date palm is dioecious, having separate male and female plants. Only the female trees can give fruit, assuming that they were pollinated by male trees. In nature or in areas with many palm trees, pollination takes place on its own. With cultivated trees, however, “grafting” was often necessary. Grafting palm trees involved placing a branch from a male branch among female trees, as closely as possible to the time that the female flowers opened. This often happened at mid-day, and there was a clear situation of monetary loss if the “grafting” did not take place at the appropriate time.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.