The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, the Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

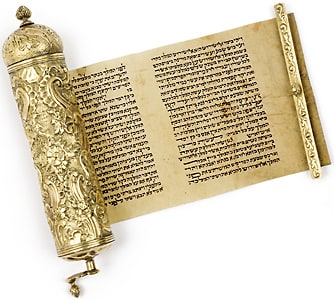

Introduction to Masechet Megillah

Masechet Megillah deals with the various laws of the holiday of Purim, as well as laws relating to the sanctity of the synagogue and public Torah readings.

The holiday of Purim is different than other Jewish holidays. Although the story of Purim – and the commandment to keep it as a day of commemoration and rejoicing – appears in the written Torah, nevertheless it is a Rabbinic rather than a Biblical commandment. There is one Biblical mitzvah that relates to Purim – the commandment to uproot and destroy the very memory of the Amalek nation – still, the holiday of Purim stands as an independent Rabbinic holiday.

The Sages note that the miracle that is celebrated on the holiday of Purim is qualitatively different than other miracles of the Bible. While virtually all miracles are considered nissim geluyim – open, obvious, miracles in which there is a clear deviation from natural norms – the Jews were saved on Purim through a nes nistar – a hidden miracle in which every incident can be explained logically. The Name of God is not mentioned even once in the megillah, and the emotional forces that drive the characters to act the way they do is obvious and straightforward.

Thus, the miracle of Purim that takes place in the Diaspora is particularly appropriate for the Diaspora. The threat originates from a capricious governmental threat, and while the threat is removed with the hidden intervention of God, there is no real change to the situation of the Jews in exile. Both the danger and its removal take place in a time of hester panim – of God’s “face being hidden.” The Sages (Gemara Hullin 139b) hint to this with their masterful wordplay “Where do we find Esther in the Torah? In the passage ve-Anokhi haster astir panai” (literally “…and I will surely hide my face [from the exiled Jews].” It should be emphasized, however, that hester panim does not indicate that God ignores His people and pays them no attention, rather that the relationship is now more distant and complicated. Therefore, Purim serves an essential purpose – to publicize and advertise the miracle; to make known what was hidden. This explains the need to celebrate in a more public and obvious way on Purim than we are commanded to on other holidays.

The central method of publicizing the hidden miracle of Purim is by reading the megillah, and therefore Masechet Megillah devotes much of its discussion to this mitzvah, including when it is to be read (we read it evening and morning, on the 14th or 15th of Adar), in what languages, who is obligated to read and hear it, and more. The other mitzvot of the day – charity, presents to friends and neighbors, a festive meal – are all based on the passage in Megillat Esther (9:22), and are discussed and clarified in this tractate.

Since a large portion of the Masechet is devoted to the public reading of the megillah, it turns out to be the only place in the Talmud where public readings of Tanach are discussed. This leads the Gemara to an extended analysis of the rules and regulations of the synagogue generally and of public Torah readings specifically, e.g. which days have public readings and how many people are called to the Torah on each of them, the rules of the Haftarah – the additional reading from the Navi – and more.

With regard to the synagogue, the Gemara emphasizes its status as a mikdash me’at – a miniature Temple, which demands the honor and respect shown to the Temple.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.