The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, the Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

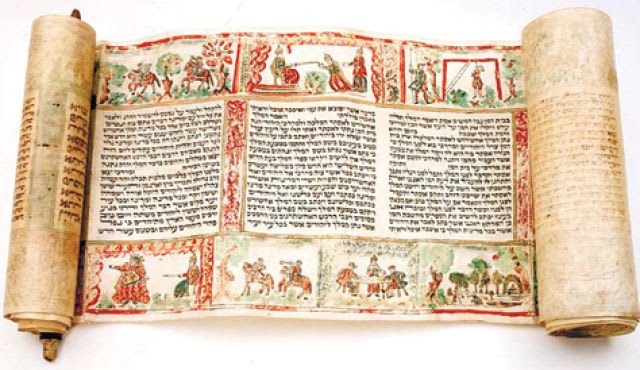

Our Gemara tells the story of the targum shiv’im, the Greek translation of the Torah organized by King Ptolemy of Egypt, who collected 72 sages, put them in separate rooms and commanded them to begin translating. According to the Gemara all of the Sages responded to a heavenly message and translated the Torah in the same way, including passages that could have been misunderstood had they been rendered in a literal fashion.

The targum shiv’im was the first translation of the Torah into a foreign language, an occurrence that the Sages viewed at first as dangerous, at best (Megillat Ta’anit records that a fast day was established in commemoration of the event). After a time, however, the translation was accepted as important and valuable and was treated with respect by the Sages. The Jews of Egypt, in particular, viewed the targum shiv’im with great reverence and saw its creation as one of holiness.

Aside from the record of the event that appears in Rabbinic literature, a lengthy description of the translation and how it came to be has been found in an ancient Greek letter entitled “the letter of Aristias,” which describes the king’s initiative to have the Torah translated and the greatness of the Sages who were brought from Israel to carry it out.

The targum shiv’im that is extant today was preserved mainly by Christians who believed it to be even more reliable than the original Hebrew. Over time, changes were introduced into the work, well beyond the changes described in the story that is told in our Gemara. Today’s version includes occasional passages that we do not have in the standard Hebrew Tanakh; there are even entire books – apocrypha – that appear in the targum shiv’im that do not appear in the Tanakh. At the same time, not all of the changes that are recorded in our Gemara are actually found in the version that we have today.

When we think of Israel as “the Holy Land,” what implications does that have for us today? Does the Land of Israel have the same holiness that it did in the days of the prophets? Does Jerusalem have unique religious holiness? Can one, for example, bring sacrifices today, even though the Temple is not standing?

The Mishnah teaches that one of the basic differences between Shilo, where the mishkan stood for 369 years after the Jewish people entered the Land of Israel following the exodus from Egypt, and the permanent mikdash in Jerusalem is that the kedushah – holiness – of Shilo ceased to exist with the destruction of the Tabernacle, but the holiness of Jerusalem remains forever.

The Gemara quotes a Mishnah from Masechet Eduyot in which Rabbi Yehoshua teaches a tradition as follows:

- sacrifices can be brought even if the Temple is not standing

- kodshei kodashim – sacrifices that need to be eaten within the precincts of the Temple – can be eaten even if there are no Temple walls in existence, and

- kodshim kalim – sacrifices that must be eaten within the city of Jerusalem – can be eaten even if there are no city walls.

His reasoning is that once the holiness of the second Temple was established, it remains for all future generations.

The idea that the holiness given to the Land of Israel may have been established in such a way that it would last forever is subject to a dispute among the rishonim.

Tosafot accept the simple reading of the Gemara, which seems to view the holiness of the Land of Israel and that of Jerusalem as being the same, so if the destruction of the Temple removes the holiness from the Land, it does so for Jerusalem as well. The Rambam, on the other hand, sees the two as distinct and rules that even if the holiness of the Land is removed, kedushat Yerushalayim – which stems from the presence of God – can never be removed. With the return of the Jews to Israel under Ezra ha-Sofer and the building of the second Temple, the center of the kedushah was the rebuilt Temple – the seat of the Almighty – and the rest of the Land derived its holiness from Jerusalem. Thus the Rambam rules that even with the destruction of the Temple, kedushat Ezra remains forever.

According to our Gemara, the party that opens Megillat Esther was thrown by Achashverosh to celebrate the fact that 70 years had passed since the Temple was destroyed and the Jews exiled, yet the Temple had not been rebuilt. The tradition of the Sages was that the Babylonian and Persian kings were well aware of Yirmiyahu‘s prophecy that the first exile would last 70 years (see Yirmiyahu 29:10), and the party described in Sefer Daniel (see Chapter 5) – where King Belshazzar brought out the Temple vessels that had been looted by Nebuchadnezzar – was celebrating the fact that the Jews had not returned to their land and that the prophecy had not been fulfilled. That party ended in disaster, with Daniel reading the proverbial “handwriting on the wall” that foretold King Belshazzar’s death. Achashverosh was convinced that Belshazzar had been mistaken in counting the 70 years from the beginning of the Babylonian empire, but that he could now celebrate, since it was 70 years since the beginning of the Jewish exile under King Yehoyakhin (see II Melakhim 24:8-16).

The Ramban explains that Achashverosh did not reject the prophecy entirely. He felt that the permission given by King Coresh to the Jews to return to Israel was sufficient for the prophecy to be considered fulfilled, but that the Temple would not be rebuilt. Some suggest that his acceptance of the prophecy is what allowed him to live, even as Belshazzar was killed.

The Ramban also explains that it was the Temple vessels that had been looted when King Yehoyachin was taken into exile that were used in King Belshazzar’s party. Those same vessels were returned to the Jewish community by King Coresh when he allowed them to return to their land. There were, however, other vessels that had been looted when King Tzidkiyahu was exiled (see II Melakhim 25:8-17), and those vessels were used by Achashverosh at his party. These vessels were eventually returned to the Jews, as well, when King Artachshasta encouraged Ezra ha-Sofer to lead the Jews back to Israel and build the Second Temple (see Ezra 7:19).

Remember the song that we sang in Hebrew school about the foolish King Achashverosh? How foolish was he? Was he truly a fool? This question is the subject of a dispute between Rav and Shmuel, who discuss whether the strategy of having a general party first and an event for the people of the capital, Shushan, afterwards was an intelligent plan or a foolish one. Did it make more sense to seek the favor of his far-flung constituency, knowing that the local populace was always available to him, or should he have first ensured his support at home?

How to judge Achashverosh is an argument that has existed through the ages. Even today, historians debate whether he was a master tactician or simply a fool. The Greeks against whom he fought – and often bested in war – succeeded in tarnishing his reputation in a variety of ways. Their description of him is not very far off from the picture that we get from reading Megillat Esther – and even more from the Midrashic material based on the megillah – of someone a bit unstable who was easily swayed by the opinions of his advisors and attendants, as well as ruled over by the women of his harem.

It should be noted, however, that in the early years of his reign, Achashverosh succeeded in putting down serious rebellions in Egypt and Babylon, securing his reputation as an astute and intelligent military tactician. His building initiatives included the cities of Persopolis and Fiura, both of which were impressive on an international scale for that time. At the same time, it appears that his spending on these initiatives was so great that he could not raise enough tax money to cover the projects, which left his treasury bankrupt.

Thus, it is difficult to reach a clear conclusion regarding his personality or his life’s work.

Much of the first perek of Masechet Megillah is devoted to a line-by-line Midrashic commentary of the pesukim of Megillat Esther. Our daf focuses on some of the goings-on in the third chapter, where we are introduced to Haman and his dastardly plan for destroying the Jews. Here are some of the interpretations suggested by the Sages to pesukim in this perek:

Haman casts lots (see pasuk 7) to decide when to unleash the masses against the Jews, and the lottery falls on the eleventh month – the month of Adar. The baraita teaches that Haman was pleased to find that the lottery had fallen on Adar, which is the anniversary of Rabbeinu’s death; he did not realize that, although Moshe died on the seventh day of Adar, he was also born on that same date. The Maharsha points out that while it is fairly simple to derive the month – and even the day – of Moshe’s death from the pesukim in Sefer Devarim, the only way to determine when he was born is by relying on the Rabbinic tradition that God allows the righteous to complete their years, by taking back their souls on the same day on which they were born.

Among the reasons Haman gives to Achashverosh for why the Jews should be destroyed is that they keep different traditions than others: They do not join in eating with others, nor do they intermarry with them, and they do not keep the traditions of the king – rather, they spend the entire year bi-sh’hi pe’hi. This enigmatic phrase is understood by most of the commentaries to be abbreviations:

- sh’hi = Shabbat ha-yom – today is the Sabbath

- pe’hi = Pesach ha-yom – today is the holiday of Passover.

In other words, they claim to have religious holidays throughout the year, which gives them more vacation days than working days!

It is difficult to determine whether this is the actual intent of the expression. In any case, it also carries the connotation of lethargy and time-wasting – she-hiya u’batalah.

Haman succeeds in convincing the king to agree to his request. In Rabbi Abba’s opinion, this is because Achashverosh was a true partner with Haman in his hate of the Jews.

Rabbi Abba bar Kahane taught: When King Achashverosh removed his ring and transferred the power over the Jews to Haman (see Esther 3:10), it brought about greater repentance among the Jews than all of the 48 prophets that had been sent by God to admonish them.

Who are the 48 Nevi’im referred to by Rabbi Abba bar Kahane?

Rashi has one set of suggestions that reaches 46 individuals and closes with the admission that there are two that he cannot identify. Among the prophet he mentions are the Avot: Avraham, Yitzhak and Yaakov. Rabbeinu Chananel offers an alternative list that begins with Moshe and Aharon and closes with Mordechai Balshan – the Mordechai of the Megillah.

The commentaries discuss the various Biblical figures that might be considered for inclusion on this list, and in particular the identity of the two individuals that should fill out Rashi’s list. Some figures are the subject of clear dispute in the Gemara. Daniel, for example, is said by the Gemara to have not been a prophet, yet he appears in some of the lists. Among the suggestions raised are Shem va-Ever and Eldad u-Medad.

According to the baraita, the only thing that these nevi’im added to the Torah was the commandment of Purim, i.e. the reading of Megillat Esther. Rashi points out that there is an additional commandment – the mitzvah to light Chanukah candles. He answers that Chanukah was established by the Sages, rather than by the prophets, which puts it in a different category of halakha. The Ran explains this position by pointing out that Rabbinic decrees are always established for the purpose of protecting Biblical commandments, or ensuring that they will be properly fulfilled. Reading the Megillah is unique in that it is an independent celebration. Tosafot Ri”d offers a simple explanation – that the intent of the baraita is to say that no public readings of the Tanakh were added aside from reading the Megillah.

Today’s daf continues sharing Rabbinic interpretations of the story of Megillat Esther.

Although Haman‘s rise to power brought with it wealth and honor (see Esther 5:11), nevertheless, the Megillah records that Haman feels that none of it is worth anything to him, so long as he sees Mordechai residing in the king’s court (see Esther 5:13).

What was it about Mordechai that so disturbed Haman?

Rav Hisda explains zeh ba be-prozbuli, ve-zeh ba be-prozbuti – this one came with wealth, i.e. claiming that debts were owed to him, and the other one came with poverty, i.e. claims made against him. Rav Papa concludes that the latter was called “a servant who was sold for bread.”

These statements refer to a well-known story that does not appear in the Talmud, but is mentioned in several midrashim. According to this story, prior to his appointment as advisor and confidant to the king, Haman was a barber and bath attendant. King Achashverosh sent both Haman and Mordechai to war as generals, responsible for different parts of the army. Haman was a poor administrator who spent his funds unwisely and could not feed or support his troops. Desperate, he turned to Mordechai and was forced to sell himself into slavery, with Mordechai becoming his master. Thus, Haman’s rise to power notwithstanding, Mordechai’s position in the king’s court was a constant threat from which Haman was desperate to free himself.

The turning point in the story of the Megillah takes place when the king cannot sleep (see Esther 6:1) and calls for the reading of the book that chronicled palace events. A number of suggestions are put forward with regard to this episode of insomnia:

- Rava says that Achashverosh could not sleep because he was concerned with Esther‘s sudden interest in having Haman over to the palace on a regular basis – a concern echoed in the king’s angry response to seeing Haman on the couch with Esther in 7:8.

- Rabbi Tanchum teaches that the “king” who could not sleep was the Almighty, King of the world. In fact, many commentaries argue that references to ha-Melekh throughout the Megillah, are, in fact, hidden references to God, who is controlling events the entire time, albeit through a veil of secrecy.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.