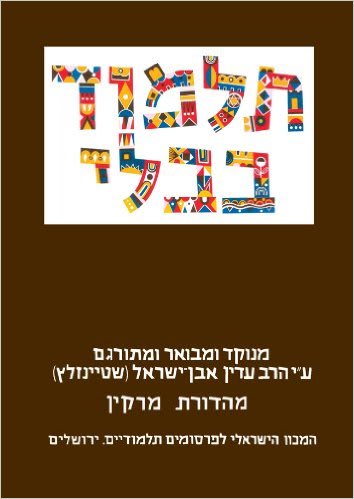

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Introduction – Masechet Chullin

Masechet Chullin is part of Seder Kodashim, the Mishnaic order whose focus is the Temple service. While Seder Kodashim is devoted to the different aspects of Temple sacrifices, including how sanctification takes place and how the offerings are brought, Masechet Chullin is entirely concerned with mundane activities. These include how to slaughter an animal and prepare it for eating, distinguishing between living creatures that are permitted to be eaten and those that are forbidden, and a series of other laws pertaining to animals that are not sanctified or related to the Temple in any way.

Although this tractate appears to deal only with mundane matters, its placement in Seder Kodashim is not accidental. Every aspect of preparation of food for mundane purposes contains not only parallels to the Temple service, but also has elements of holiness attached to it. For example, the laws of shechita – kosher slaughter – concern themselves with the people who are appropriate for this religious requirement and the intent that is required while performing it. In general, all of the laws that appear in Masechet Chullin that appear to be entirely mundane, have an element or aspect of religious sanctity.

From a broad perspective, this is true of the entire Torah, which deals with a wide range of laws that affect all aspects of life, yet is grounded in holiness. Even the legal portions of the Torah, whose economic laws, for example, appear to be concerned solely with creating an orderly society, are truly dealing with issues of sanctity. Moreover, these very laws add an element of separation and uniqueness that emphasize that what appear to be mundane activities are, in fact, suffused with religious and spiritual significance. This is true not only with regard to financial matters, but also marriage and family, as well as issues having to do with food and eating.

The laws pertaining to flora appear in Seder Zera’im, which deals with the gamut of rules and regulations regarding fruits and vegetables used by people, while offering an element of religious sanctity to them. Masechet Chullin deals with the laws pertaining to fauna – identifying them and explaining how they must be prepared – and offering a general perspective that there are things that are forbidden and things that are permitted; things that are appropriate to use and things whose use would be inappropriate. This concept appears in the language of the Torah where we find that in those places where the rules of ritually pure animals are contrasted with those that are forbidden, the concept of holiness is repeated (see Vayikra 11:44 and Devarim 14:21) to teach that these laws are part-and-parcel of the rules of ritual sanctity. Thus, the concept of holiness is not limited by the Torah to the Temple, rather mundane life outside of the Temple also contains elements of holiness and every Jewish person going about his daily life is involved with issues of sanctity.

The laws of kosher slaughter and tereifot (when an animal is suffering from a fatal condition), which are central parts of this tractate, contain many parallels to Temple laws. Although the laws of the Temple are more ceremonial than those of Chullin slaughter, nevertheless even ordinary food preparation retains the same basic structures. For example, animals that suffer injuries and become blemished (ba’alei mumin) cannot be sacrificed or eaten in the Temple, similarly tereifot are forbidden to all, and they are similar to ba’alei mumin in that they can no longer serve the needs of the Jewish people.

So on some level, Masechet Chullin does not really focus on mundane matters, but on sacred ones, inasmuch as its laws serve no rational, utilitarian purpose, rather their source is in a religious system, which is not Temple-centered, but is, nonetheless, focused on a holy nation – the Jewish people.

All of the forbidden elements dealt with in Masechet Chullin – which are mainly focused on what is forbidden and permitted from among living creatures – contain a kernel of a different concern, which is not mentioned outright in the Torah, but is hinted at in a number of places. That is, the basic concept permitting human beings to kill other living creatures in order to derive benefit from them is not part of the original Divine concept in the creation of Man (see Bereshit 1:29). Although the Torah ultimately permits the slaughter and consumption of animals by humans, there is a sense of exigency of sorts, which creates a need to show extreme care and concern when dealing with these situations. This explains the need to limit the means and methods of killing them, and the care that is required in preparing the meat for consumption. These requirements hint to the fact that although the Torah permits eating animal flesh as it does vegetables (see Bereshit 9:3), still respect must be given to the life-force that they contain.

Inasmuch as most of the laws in Masechet Chullin are related – directly or indirectly – to shechita, for generations this tractate was referred to as Shechitat Chullin (“mundane slaughter”) in contrasts with Masechet Zevachim, which was known as Shechitat Kodashim (“sacred slaughter”). Nevertheless, as a segue from the laws of ritual slaughter, two topics are discussed in this tractate that are not directly related to shechita. These are the laws of ta’arovet – forbidden mixtures – and laws related to taharot – ritual purity – in particular the laws of tumat ochlim (ritual defilement of food).

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.