The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Chullin 47a-b: Genetic conditions and the color of newborns

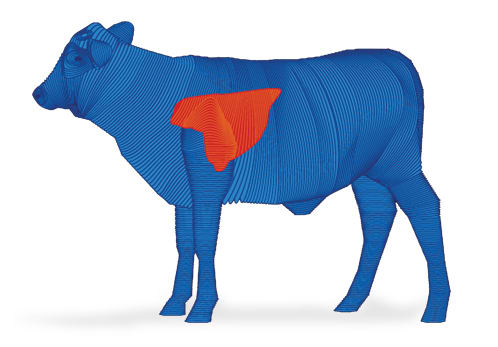

In the context of discussing the significance of the lungs of an animal as appearing different colors – blue, black, green or red – the Gemara quotes a baraita that tells of newborn babies whose appearance is out of the ordinary.

Rabbi Natan said: ‘I once came to a coastal town and was approached there by a woman who, having circumcised her first son and he died and her second son and he also died, brought her third son to me. I saw that the child was red so I said to her, “My daughter, wait until the blood will become absorbed in him”. She accordingly waited and thereafter circumcised her child and he lived and was named Natan the Babylonian after me. On another occasion when I went to Cappadocia I was approached by a woman who, having circumcised her first son and he died and her second son and he also died, brought her third son to me. I saw that the child had a greenish color; I examined him and found that he was anemic, without blood for circumcision. I said to her, “My daughter, wait until the blood will circulate more freely in the child”. She accordingly waited and thereafter circumcised her child and he lived and was named Natan the Babylonian after me’.

A number of different medical explanations are offered for the conditions that these babies – who were successfully treated by means of Rabbi Natan’s advice – were suffering.

Some suggest that the children who appeared red were suffering from a rare genetic condition called neonatorum purpura.

It is likely that the children who appeared green were suffering from hemolytic jaundice of the newborn. Hemolytic jaundice is a rare, chronic, and generally hereditary disease characterized by periods of excessive hemolysis due to abnormal fragility of the red blood cells, which are small and spheroidal. It is accompanied by enlargement of the spleen and by jaundice. The hereditary form is also known as familial acholuric jaundice; there is also a rare acquired form.

Chullin 48a-b: An animal with ulcers on its lungs

The discussion on today’s daf continues the conversation regarding different conditions found on the lungs of animals and the effect that they would have on the kosher status of the animal.

Rabbah bar bar Hana inquired of Shmuel, ‘What is the law if there was an eruption of ulcers on the lungs?’ — He replied: ‘It is permitted.’ ‘I also said so,’ said the other, ‘but the students were hesitant about it, for Rabbi Mattana stated, if the boils are full of pus it is treifah; if full of clear water it is permitted.’ ‘That statement,’ replied Shmuel, ‘was made with regard to the kidneys.’

Rabbi Yitzhak bar Yosef was walking behind Rabbi Yirmiyah in the butchers’ market and they noticed certain lungs with ulcers. Rabbi Yitzhak said to Rabbi Yirmiyah, ‘Master, would you care to buy of this meat?’ He replied: ‘I have no money.’ ‘I can get it on credit for you,’ he said. The other answered: ‘Why should I put you off?’ Whenever such a case as this came before Rabbi Yochanan he would always send it to Rabbi Yehuda son of Rabbi Shimon, and the latter, on the authority of Rabbi Elazar son of Rabbi Shimon always ruled that it was permitted; though Rabbi Yochanan himself did not hold that view.

Rashi explains that Rabbi Yochanan did not rule unequivocally that such an animal was to be considered to be unkosher, since he did not have such a tradition from his own teachers, yet at the same time he was reluctant to permit the animal, so he sent the question to Rabbi Yehuda who had a clear tradition permitting it. The Me’iri offers an alternative approach, suggesting that Rabbi Yochanan’s inclination was to forbid such an animal, but he directed the questioners to other authorities who permitted it. The Me’iri further suggests that a scholar who is asked to make a ruling in such a case would not need to direct the questioner to the authority who rules leniently; it would be enough to simply state that a particular rabbi permits and the questioner could rely on that ruling even if he knows that the authority he approached does not accept that view.

Chullin 49a-b: Holes in an animal’s lungs

Although the Mishnah (daf 42a) teaches that an animal that is found to have a hole in its lung will be deemed a treifah, there are a number of circumstances where we may assume that there are other circumstances that caused the hole to appear after the animal had already been slaughtered. If we are convinced that there is a good likelihood that the hole was caused by such factors, the animal will be declared kosher. Thus, if we know that the butcher had dealt with the lungs in a manner that would likely have torn them, we can assume that the animal is kosher. The Rama (Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De’ah 36:5) adds that this is only true if the appearance of the hole corroborates that assumption. If, however, the indications are that the hole existed while the animal was alive, e.g., it was perfectly round or the flesh around the hole was discolored, then we could not make an assumption that would permit the animal.

Another such situation is when we see that the hole in the lung was caused by a parasite, like a morena. Must we assume that the parasite ate its way through the lung while the animal was still alive, rendering it a treifah – or can we rely on the fact that the parasite first made the hole after the animal had been slaughtered? The Gemara concludes that we can rely on the fact that such a hole was made after the animal had been killed. Rabbeinu Yehonatan and the Me’iri explain that in this case we know that these parasites do not leave the body of their hosts until they have died, which is why we can say with some level of certainty that the hole first appeared after slaughter.

It is common for animals to act as hosts to a number of different types of parasites, many of whom live as adults in the intestines of the animal, where they lay eggs. From the digestive system the eggs or newly hatched worms make their way to other internal organs of the animal where they develop. Such parasites make their way from the intestines to the lungs by way of the stomach and/or blood vessels. The morena – or, in Latin, muraena – is one such parasite.

Chullin 50a-b: Identifying the source of holes in the lungs

As we learned on yesterday’s daf, not all holes discovered in an animal’s lung automatically render it non-kosher. Even in cases where the assumptions that we learned about do not apply, there are tests that can be performed to clarify where the hole came from and whether the animal must be declared a treifah because of it. Thus, we learn on today’s daf, that Rabbi Yochanan and Rabbi Elazar agree that if a hole is found on an animal’s lung – and it cannot be attributed to a factor that would allow the animal to be permitted – a similar hole can be made so that a comparison can be performed. If the two holes look the same, we can assume that the first hole – like the second one – developed after the animal was slaughtered and the animal is considered kosher.

A number of limitations are suggested by the Gemara regarding this test.

Rava suggests that the comparison can only be made on a single lung, but cannot be made from one lung to the other. This suggestion is rejected by the Gemara. The Gemara concludes, however, that comparisons can only be made between similar animals – one gasah (a large animal) to another or one dakah (a small animal) to another– but cannot be made between a gasah and a dakah.

This last ruling follows Rashi‘s first interpretation of the Gemara, as well as that of the Rambam and Rabbeinu Chananel. Rashi expresses doubt about this ruling, arguing that any comparison between two different animals cannot be reliable, even if the animals are similar. For this reason he prefers an alternative explanation of gasah and dakah in this case, where they refer to the larger lobes or the smaller lobes of the lungs, so that only similar lobes can be compared.

The clear ruling of the Gemara notwithstanding, the Rama (Shulchan Aruch Yoreh De’ah 36:5) argues that we are no longer expert in this method and that there is no longer a tradition to rely on tests like these to permit an animal.

Chullin 51a-b: When an animal takes a bad fall…or a leap of faith

According to the Mishnah (daf 42a) if an animal fell from a roof it is a treifah, since we fear that its internal organs were injured by the fall. The simple reading of the Mishnah appears to rule that even if there was no external evidence of injury, nevertheless we must make this assumption if the animal was slaughtered immediately. From the Mishnah later on in the perek (see daf 56a) it is clear that if they wait a 24-hour period before slaughter, the animal is kosher, as we can be certain that there was no serious internal injury.

On today’s daf the Gemara quotes Rav Huna as teaching that if an animal was left on the roof and was later found on the ground, we do not assume that it fell and the ruling of the Mishnah is not applied to it. To illustrate and clarify this ruling, the Gemara relates the following story:

A goat belonging to Ravina was on the roof and through the sky-light saw some peeled barley below. It jumped and fell down from the roof to the ground. Ravina came before Rav Ashi and asked: Was the reason for Rav Huna’s statement, ‘If a person left an animal on the roof, and returned and found it on the ground we do not apprehend a lesion of the internal organs,’ that it had something to hold on, but in this case it had nothing to hold on; or was it that the animal estimated the distance, so that here too it estimated the distance? — He replied. The reason was that it estimated the distance; so that here too it estimated the distance and it is therefore permitted.

The Rashba concludes from this story that the ruling of the Mishnah is limited to cases where the animal fell, but it does not extend to cases where the animal chose to jump, since in such cases the animal gauges whether it will be injured. Furthermore, if we do not know how the animal reached the ground we do not assume that it fell – which is an unusual occurrence – rather that it jumped. According to the Rashba, there is no need for any further assessment of the animal, even if it no longer stands, but other rishonim argue that even if the concern with internal injury does not apply, still we must worry that some other injury may have taken place that might render the animal a terefah, since we know that even a simple fall suffered by a human being can sometimes lead to death.

Chullin 52a-b: Predatory animals

While the Gemara uses the term treifah to denote any animal with a terminal condition that cannot be slaughtered as kosher since it will die within a short amount of time, the single case of terefah that is mentioned in the Torah is when an animal attacks another animal and kills it (see Shemot 22:30). This most basic case occurs when the predator locks its claws on the body of the animal that is being attacked, and the poison in its claws enters the animal, threatening its life, According to the continuation of the Gemara, this poison “burns” in the body of the animal, injuring and puncturing its internal organs, which renders it a terefah.

The example of a terefah that appears in the Mishnah is a wolf, and Rav Yehudah quotes Rav as teaching that in the case of cattle it is “from the wolf and upwards,” i.e. either a wolf or animals larger than a wolf like a lion. Ultimately the Gemara suggests that this teaching comes to exclude the case of a cat that attacks in a predatory manner. While I might have thought that the Mishnah simply mentions ordinary cases of attacking animals, but that smaller animals would be included as well, Rav Yehuda teaches that in the case of cattle an attack by a cat would not be considered significant to render the animal a treifah.

A wolf, canis lupus, is a predatory animal, similar to a dog. It grows to a length of between 3 and 5 feet and an adult can weigh up to 130 pounds. Wolves live and hunt in packs, which allow them to hunt not only small animals, but larger animals, as well. An attack by a pack of wolves can cause serious damage to a herd of cattle.

A cat, felis, is a relatively small predator that weighs between 7 and 15 pounds. We are most familiar with the common house cat – F. silvestris catus – but there are numerous types of wild cats, as well. From the Talmud it appears that there were ferocious wild cats that lived in close proximity to human habitation during the time of the Sages. These cats attacked animals much larger than themselves, such as sheep and goats, and there is even reference to a case when a child’s hand was bitten off by such a creature.

Chullin 53a-b: Indications that a predator may have attacked

The Gemara continues with its discussion of predatory animals that began on yesterday’s daf and relates the following:

Rabbah bar Rav Huna said in the name of Rav: If a lion had entered amidst oxen and later there was found a nail from a lion’s claw lodged in the back of one of them, there is no fear that the lion had clawed it. Why? Because although most lions attack with their claws there are a few that do not; moreover, all that do claw do not usually lose a nail, therefore the fact that this ox has a nail lodged in its back suggests that it had rubbed itself against a wall.

Rabbeinu Tam expresses surprise at the Gemara’s willingness to assume that most attacking animals do not lose nails from their claws, which leads to a conclusion that we need not be concerned with attacks in such cases. Surely since the majority of lions attack, once we ascertain that the lion was among the cattle all of the animals will need to be checked lest they were attacked! He concludes that when the Gemara states that “the majority of lions attack” it refers to healthy lions, and the minority that do not attack are sickly lions. Since healthy lions do not ordinarily lose the nails from their claws we can conclude that in this case the nail found on the ox did not come from an attack by a healthy lion. We therefore do not need to be concerned about the other oxen.

The Gemara continues, concluding that there are cases where we must fear that the animal was truly attacked:

Abayye said: This is the rule only when the nail was actually there, protruding from the back of the ox, but if there was found the mark of the nail of a claw upon the back, we are certainly apprehensive about it. And even when the nail was actually there this rule applies only if the nail was moist with blood, indicating that it was well attached to the lion, but if it was dry it is quite usual for it to fall loose. And even when the nail was moist the rule applies only to a single nail, but if there were two or three nails upon the back of the animal we are apprehensive about it; provided, however, they were in the shape of a paw.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.