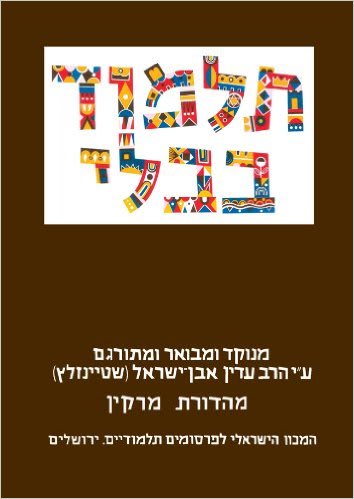

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

Introduction: Masechet Horayot

Masechet Horayot deals with mistakes made by Jewish courts and by Jewish leaders, and the atonement sacrifices that are brought as a consequence of those errors.

Although the focus of the Tractate deals with the sacrificial service, and it would appear that the proper place for it would have been in Seder Kodashim, it appears in Seder Nezikin because it, too, serves as a continuation and completion of Masechet Sanhedrin. After learning the rules and regulations that apply to the Jewish court system, and specifically to the Great Sanhedrin that legislates and rules on capital crimes, it is important to also address the issue of how to deal with mistakes. It is impossible to avoid all circumstances of errors and mistakes, so we must be prepared for such situations, including arranging for atonement for them.

The laws regarding the sacrifices that are to be brought in these situations appear in two separate places in the Torah – Vayikra 4:1-35 and Bamidbar 15:22-29, and the Sages of the Talmud explain that the first one discusses mistakes made in any of the applicable mitzvot of the Torah, while the second one deals specifically with mistakes made in the realm of idol worship.

When the Torah says “if the entire People of Israel sin…” (Vayikra 4:13) or “if it be done in error before the congregation” (Bamidbar 15:24) the reference is understood as talking about a sin committed by the community at large. If an individual were to commit a sin, it may be done because he forgot or did not know the law; if an entire community commits the sin, however, it points to a mistake made by the leadership that pulls the entire community in its wake.

The Torah views the Great Sanhedrin as the ultimate authority, from whose words it is forbidden to deviate “to the right or to the left” (see Devarim 17:8-13). Thus we must assume that it is this group that has erred and who will need to recognize their error and act to rectify it. Since it is the greatest religious authority that has erred, it is clear that they did not make a mistake in a clear Torah law. (Although there were periods in Jewish history when even the leadership did not follow the Torah, it appears that in those cases there was a conscious rejection of Torah laws, rather than misunderstandings or mistakes.) Thus it is logical to conclude that the mistake was an error in interpretation or application of the Torah’s laws.

Aside from the Sanhedrin, the Torah includes two other leadership figures in its description of situations where the community commits a transgression. The kohen gadol (referred to as the moshiach) and the king (referred to as the nasi) are the highest ranking individuals in the spiritual realm and the political realm. These two positions have their own sets of laws (see Vayikra 21:10-15; Devarim 17:14-20), and the individuals who hold these positions have unique obligations and bring different sacrifices than do ordinary members of the Jewish community.

Since Masechet Horayot deals with these unique individuals and their positions, it also raises for discussion the different levels of community membership. The Torah itself distinguishes between different groups of people, each with their own community status and responsibilities – e.g. kohanim, Levi’im, Yisraelim; people who are restricted in who they can marry, the judge on the one hand and the convert, widow and orphan on the other.

Establishing these different levels is not merely an issue of who deserves honor, but it serves as the basis for setting priorities within the community. While in theory every Jewish person deserves to receive according to his needs, whenever the demand outstrips the available resources there will be a need to prioritize and triage. Decisions on such questions as who should be appointed to a given position or who should receive priority in the receipt of scarce resources would better be taken based on Torah laws rather than on some arbitrary system.

These are the topics that are found in Masechet Horayot, although, as is commonly found in Talmudic discussions, other issues that are directly or even tangentially related are included, as well.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.