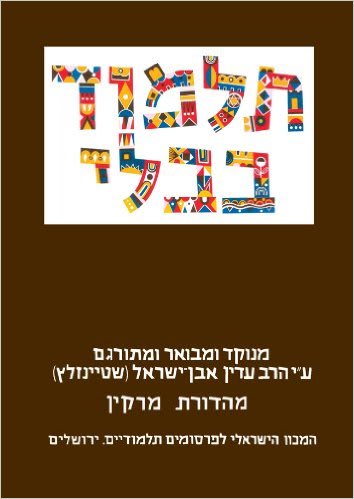

The Coming Week’s Daf Yomi by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz

This essay is based upon the insights and chidushim (original ideas) of Talmudic scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, as published in the Hebrew version of the Steinsaltz Edition of the Talmud.

This month’s Steinsaltz Daf Yomi is sponsored by Dr. and Mrs. Alan Harris, the Lewy Family Foundation, and Marilyn and Edward Kaplan

Masechet Beitzah – An Introduction to the Tractate

Following the lengthy discussions of the rules and regulations of Shabbat, Yom Kippur, Pesach and Sukkot, in Masechet Beitzah we turn our attention to the general halakhot of Jewish holidays that are not specific to one particular Yom Tov. In fact, most of the rishonim refer to our Masechet as Yom Tov; its popular name – Beitzah – is simply the first word of the first Mishnah.

The most basic, overarching rule that is common to all of the biblical holidays is shevitah – cessation of productive activity – as indicated in Vayikra, chapter 23, verses 7, 8, 21, and 24-25. The conditions of shevitah, along with the Rabbinic ordinances enacted to protect against accidental activities and to enhance the spirit of holiness of the day, are similar to those of Shabbat. Thus, this Masechet can be seen as an extension of Masechtot Shabbat and Eruvin, where the sources for these halakhot can be found. The main task of our tractate is to highlight the differences that exist between the way these rules are kept on Shabbat and on Yom Tov.

There are, in fact, two main issues of divergence between Shabbat and Yom Tov:

- The 39 activities that are biblically prohibited on Shabbat carry with them a death penalty (see Shemot 31:14) if they are done with full knowledge of the act and its consequences. The same activities performed on Yom Tov are, at worst a mitzvat lo ta’aseh – a prohibition for which one will receive lashes from the courts.

- A more basic difference involves the activities themselves. On Yom Tov the Torah clearly permits food preparation (see Shemot 12:16). Defining which activities fall into the category of okhel nefesh – food needed for the holiday – is one of the major foci of Masechet Beitzah.

It is clear to the Sages that not all activities that are related to preparing food will be permitted on Yom Tov, although the rishonim disagree as to whether this division is biblical or Rabbinic in its origins. Trapping animals, for example, is so far removed from the actual food preparation that it is not permitted, while baking and cooking are seen as examples of okhel nefesh.

Although permitting food preparation on Yom Tov is a biblical law, the Sages felt it necessary to limit some aspects of the preparation in order to ensure that the laws of Yom Tov are taken seriously, lest the holiday be treated as a regular weekday. In certain cases, the Sages were even more stringent regarding Yom Tov than they were about Shabbat, since the lesser punishment and permissibility of some activities were seen as creating the potential for people to regard Yom Tov as a less serious day. At the same time, the Sages needed to keep in mind that there is another aspect to Yom Tov. Aside from forbidden activities, there is a positive commandment to be joyous on the holidays (see Devarim 16:14-15), which is understood as encouraging eating and drinking as well as wearing special clothing for the holiday (see Pesachim 109a). Therefore, care had to be taken to ensure that the Rabbinic prohibitions would not limit the opportunity to fulfill the positive elements of the holiday commandments. Striking the appropriate balance between the prohibitions and commandments of Yom Tov is one of the challenges faced by the Sages in our Masechet.

There are two other topics of concern that are discussed in Masechet Beitzah. One is the need to deal with situations when Yom Tov falls out on Friday and there is a need to prepare for Shabbat while minimizing the impact that such preparations will have on the holiness of the holiday. The other is the age-old tradition of adding an extra day of Yom Tov to the holidays in the Diaspora, a practice that began at a time when the difficulties of communication led to a situation in which many communities were not certain of the correct day of the holiday. The tradition is kept to this day for a variety of reasons discussed in our Gemara.

In addition to his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud, Rabbi Steinsaltz has authored dozens of books and hundreds of articles on a variety of topics, both Jewish and secular. For more information about Rabbi Steinsaltz’s groundbreaking work in Jewish education, visit www.steinsaltz.org or contact the Aleph Society at 212-840-1166.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.