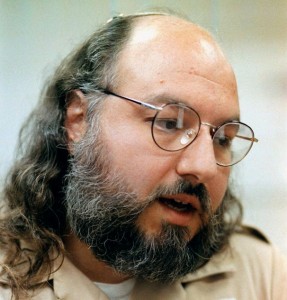

Jonathan Pollard is scheduled this month for release after spending thirty years in prison. He was sentenced to life in prison after pleading guilty to spying on the United States. There are two possible responses to release after such a long sentence. One is to become bitter over the time lost, the life that could have been lived. The other is to be grateful for the end of the ordeal, the new beginning. I cannot fathom the depth of his experience but I hope he can find his way to seeing the opportunities in his future.

If he is released, he will face an interesting halakhic question: Should he bentch gomel, recite the traditional blessing thanking God for salvation? This is a response of hope, of seeing the end of the past and the beginning of the future. His ability to recite this blessing lies in the conditions of his imprisonment and release. As always, the details make all the difference.

I. Four Salvations

The Gemara (Berakhos 54b) says that four people need to bentch gomel: someone who travels by sea, journeys in the desert, becomes healed from illness or exits prison. These four categories are derived from Psalm 107:

- travel by sea – “they that go down to the sea in ships” (v. 23)

- journey in the desert – “they wandered in the wilderness in a desert way” (v. 4)

- healed from illness – “He sent His word, and healed them, and delivered them from their graves” (v. 20)

- released from prison – “such as sat in darkness and in the shadow of death, being bound in affliction and iron” (v. 10)

Tosafos (Berakhos 54b av. Arba’ah) point out that the Gemara’s list follows a different order than the Bible’s. Why does the Gemara skip back and forth in that Psalm? Tosafos answer that the Bible lists the cases in decreasing order of danger: first those traveling in the desert, then those sitting in prison, then those suffering illness and finally those traveling by sea. In contrast, the Gemara lists the cases in order of frequency, those more common appearing earlier in the list. However,Talmidei Rabbenu Yonah (quoted in Ma’adanei Yom Tov, Berakhos9:30) quote a responsum of Rav Hai Ga’on in which he explains it directly opposite. According to Rav Hai Ga’on, the Gemara lists the cases in the order of danger while the Bible lists then in order of frequency. It seems that according to Tosafos, both the imprisonment and illness on which this blessing is recited must be life threatening. According to Rav Hai Ga’on, this need not be true because they are less severe than traveling by sea and journeying through the desert.

II. Severities

Two general approaches emerge in the commentaries regarding this blessing. Ashkenazic authorities tend to see this blessing as reserved for those who emerge from life-threatening situations. For example, the Rosh (Berakhos 9:3) says that the custom in Germany and France is to refrain from reciting this blessing when traveling from city to city because there is no danger to life. He also quotes the Ri Migash who rules that only someone who recovers from a serious illness should recite this blessing. The Ra’avad (quoted in Birkei Yosef, Shiyurei Berakhah, Orach Chaim 219:1) rules that the blessing only applies to a life-threatening illness.

However, the Rosh notes, the Arukh implies that even someone whose headache goes away should recite this blessing. Similarly, in a responsum, the Ri Migash (no. 90) rules that someone who is released from debtors’ prison–i.e. who faced no threat to life–should recite the blessing. According to the Ri Migash, the blessing on release from prison is about regaining freedom, not salvation from death.

The Shulchan Arukh (Orach Chaim 219:8) rules that you recite this blessing after recovering from any serious illness, even if it was not life threatening. However, the Rema (ad loc.) says that the Ashkenazic practice is to only recite the blessing after a life threatening illness. Similarly, the Magen Avraham (ad loc., 1) writes that you only recite the blessing after exiting a life threatening imprisonment. The Birkei Yosef (ibid.) argues that release from any prison sentence merits recitation of the blessing, like the Ri Migash.

III. Recent Authorities

Based on all the above, it would seem that Sephardim–who generally follow the Shulchan Arukh andBirkei Yosef–would recite the gomelblessing on release from prison regardless of the sentence. Ashkenazim–who generally follow the Rema and Magen Avraham–would only recite the blessing on release from a death sentence.

The Mishnah Berurah (219, Bi’ur Halakhah sv. chavush) explains that the Magen Avraham‘s view is based on a life threat. Regardless of the sentence, if the prisoner faced a life threat–such as being held in a highly dangerous prison–then he should recite the blessing. TheMishnah Berurah adds that the Magen Avraham‘s ruling was intended even for Sephardim who follow a more lenient view on this blessing. Since the Shulchan Arukh rejects the view of the Arukh that even a minor illness merits this blessing, he requires a serious illness that could lead to a life threat. Similarly, the Shulchan Arukh requires an imprisonment that could lead to a life threat, not just a minimum security prison stay.

However, the Kaf Ha-Chaim (219:11)–an important Sephardic authority–rules that even someone imprisoned in a comfortable prison for a monetary matter should recite the blessing. Following the Ri Migash, he explains that the blessing here refers to a lack of freedom. Once that freedom is regained, you should saying the blessing.

The first Lubavitcher Rebbe, in his discussion of blessings in his prayerbook (Seder Birkos Ha-Nehenin 13:2), takes a middle position. He says that someone released from a death sentence or from prison on a monetary matter for which he was held in chains recites the blessing. The aspect of being held in chains is a reference to the language of the verse (Ps. 107:10), “being bound in affliction andiron.”

The Arukh Ha-Shulchan (209:25) adds another consideration. On the one hand, he rules leniently that even someone released from prison on a monetary matter recites the blessing. However, he explains that this view–of Ri Migash–connects the blessing to renewed freedom. Someone released from a lengthy prison stay, for whatever reason, regains his freedom, for which he recites the gomel blessing. But this only applies if he is truly free without any conditions. If, for example, he is subject to home arrest then he cannot recite the blessing because he is not truly free.

Rav Eliezer Melamed (Peninei Halakhah, Berakhos 16:11 and in hisHarchavos, as loc.) says that most authorities–Ashkenazic and Sephardic–rule that someone released from prison for a long stay recites the blessing. He offers two reasons: First, like the Ri Migash, many believe that this blessing applies to renewed freedom. Additionally, any extended imprisonment involves at least a little threat to life.

IV. Conclusion

Should Jonathan Pollard bentch gomel on his release? On the one hand, he was never given a death sentence so a simple reading of theMagen Avraham would imply that he should not recite the blessing. However, the Mishnah Berurah adds that any threat to life while in prison would merit a blessing on release. If his prison stay was at any time life threatening, then he would recite the blessing. On his release, he will be free from the position of possibly being in a life threatening prison situation.

Other authorities are more open to the blessing because they see it as a response to regaining freedom. On his release, Pollard will gain his freedom and therefore, presumably, should recite the blessing.

However, the conditions of his release also make a difference. If he is released to home arrest then everyone agrees he should not recite the blessing. Additionally, if his movement is restricted within the country, he would not recite the blessing because he lacks freedom. I suspect, but am not certain, that if he may not leave the country, then he should not recite the blessing. But I leave that to his rabbi to decide.

This article originally appeared on Rabbi Student’s blog.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.