More than once, when I really need my friend’s help and “no” is simply not an option, I’ve asked for commitment before my request. The conversation might go like this:

“Can I ask you a favor?”

“Sure, what can I do for you?”

“In a moment. First, just say yes.”

Usually, they don’t say yes.

But the Jews said yes.

Moshe wrote down all the words of Ad-noy. He arose early in the morning, and built an altar beneath the mountain, and [also] twelve monuments [pillars] for the twelve tribes of [the B’nei] Yisrael. .. and they offered burnt-offerings, and sacrificed oxen as peace-offerings .. Moshe took half the blood and put it in the basins, and [the other] half the blood he sprinkled on the altar. He then took the Book of the Covenant, and read it in the ears of the people. They said, “All that Ad-noy has spoken, we will do and we will listen.” [Na’aseh v’nishma]

After [Moshe’s] reading the book, we entered the covenant mouthing our triumphant words of na’aseh v’nishma; a seminal phrase, Rabbinically understood to be akin to “Yes, whatever it is, we’ll do it! Then we’ll try to figure it out” (Shabbos 88). Our utter irrationality that confounds the world-nations; in their view we are an ama peziza –“a foolish hasty nation that puts its mouth before its ear”.

People in love do crazy things. A rich Rabbinic analogy likens our Torah acceptance to marriage.1 First, it is a lifelong commitment; more precisely, it is an essentially unknowable journey. Na’aseh v’nishma encompasses the heilige madrega (holy level) of a people ready to take the Divine plunge with no real inkling of the depth of its commitment.

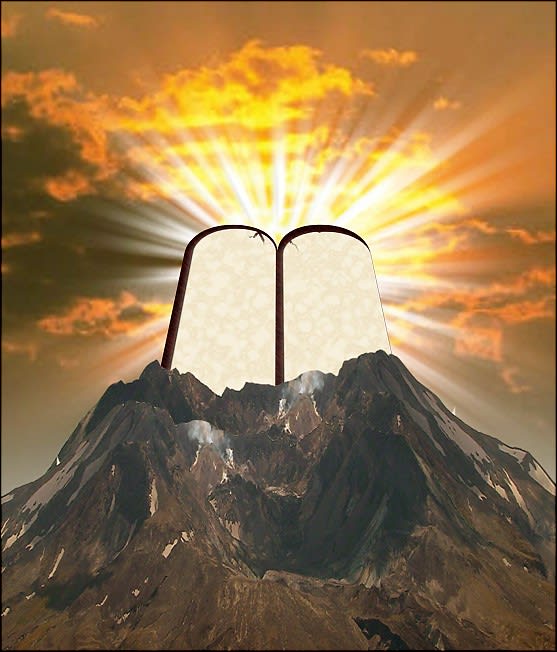

The pashtan (textual analyst of Torah) might balk. Is it really true that the Jews had no clue? Na’aseh v’nishma appears in chapter 24 while the Aseret HaDibrot (Ten Commandments) are in chapter 20, followed by the myriad, complex and detailed laws of Mishpatim; statutes that encompass major Talmudic tractates 2 and a veritable lifetime of learning. Thus, as Moshe ascends the mountain for a forty day rendezvous with the Almighty and Bnei Yisrael are “preparing” for the Sinai Revelation, surely they had more than a ta’am, a taste of the Torah’s massive scope?!

Rashi, [citing Rabbinic tradition], opts for ein mukdam u’meuchar batorah, i.e. we are not bound to chronology in Torah. Even as na’aseh v’nishma is presented following the Aseres HaDibros and Mishpatim, it actually takes place beforehand.

What’s in that Sefer Habris – the covenantal book Moshe read to Bnei Yisrael just prior to their exalted response? For Rashi, it is the narrative of human history; Creation through Exodus, spanning twenty six generations from Adam to Moshe and a smattering of a few mitzvos they received in Marah. Primarily, then it is a book of an inspirational history of Matriarch and Patriarchs who stood up for Divine morality and weathered great challenges in order to infuse the world with knowledge of Hashem. It is a powerful story for the heart.

For Rashi, then, the idealistic, gung-ho, na’aseh v’nishma remains in place.

Ramban, axiomatically rejects this approach. De facto, Torah is always in chronological order unless we find an explicit source to the contrary. 3 Na’aseh v’nishma took place after the Jews heard the Ten Commandments and had been exposed to the sundry details of Jewish jurisprudence. Indeed, this constituted the essence of the sefer habris – a book that challenges the mind to the max!

My first exposure to Ramban left me on a downer. If Bnei Yisrael knew what to expect, did na’aseh v’nishma mean as much? A reasoned rational decision diminishes the great Divine plunge and removes luster from a previously pristine na’aseh v’nishma.

But since that visceral response, I have changed my mind.

Ever notice at a wedding that are usually two distinct groups of guests: 1. Chosson-Kallah and their friends 2. Parents and their friends. Both smile, dance, laugh and enjoy. Perhaps one group is a bit more energetic and the other somewhat sedentary, but they are essentially united in mirth – or so it seems. Perhaps it’s a tad cynical, but maybe their reflective joyous states differ.

For the first group, there is an incredible purity and idealism associated with the wonder of marriage; let’s call it blessed naivete. Zeh hayom kivinu lo, this is the day and the moment we have pined for. The second group, we shall call them the veterans, also smile. It’s a different type of smile, one laced with a bit more experience. Yes, the second chevra are moved by the pristine and beautiful moment of love; they are also armed with the retrospective knowledge of the challenges, meanderings and vicissitudes of life. They smile as they remember their innocence and for but a moment, perhaps they have even regained it, but their grin might also be enhanced [just a tiny bit] by the delicious realization that the first group knows not a clue of what lies ahead.

What Ramban’s na’aseh v’nishma lacks in naivete and idealism it more than makes up in gravitas and experience. Bnei Yisrael’s rational knowledge could have been a hindrance to their acceptance of Torah. Their na’aseh v’nishma was not per se a Divine leap of faith as much as it was a leap of knowledge; they said na’aseh v’nishma with the realization that great challenges lie ahead. Perhaps, Ramban’s na’aseh v’nishma is like the couple that get married a little later in life, armed with more self knowledge and more real with their challenges.

Which is greater – To commit without knowing exactly what’s in store or to accept in spite of the immense clarity of the challenges that lay ahead? They are different avodahs (tasks). The first is emunah peshutah (simple, pristine faith) and the second emunah amukah (deep, rational faith). One challenges the heart, the other confronts the mind – both critical in the formation of a complete Jew.

FOOTNOTES:

1 The mountain over the head = the canopy. Cf. Ta’anis 29. Also Torah tzivah lanu morasha = me’orasa (betrothal)

2 Bava Kamma, Metzia, Basra, Sanhedrin, Makkos, etc.

3 cf. Bamidbar, 9:1 with Rashi

Rabbi Asher Brander is the Rabbi of the Westwood Kehilla, Founder/Dean of LINK (Los Angeles Intercommunity Kollel) and is a Rebbe at Yeshiva University High Schools of Los Angeles

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.