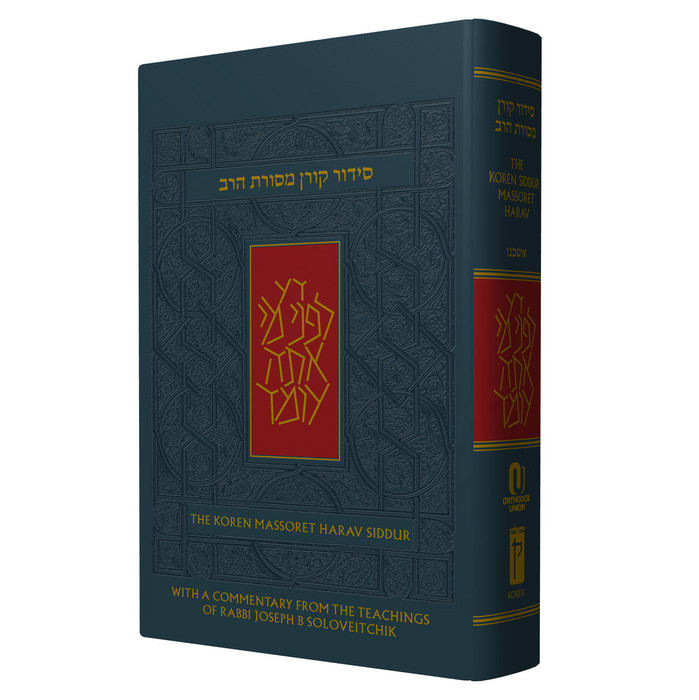

Students of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik (the Rav), satisfied users of the Koren Sacks Siddur and anyone looking to gain insight into the meaning of Jewish prayer will rejoice at the upcoming publication of the Koren Mesorat HaRav Siddur: The Berman Edition. This complete Hebrew-English siddur follows the commentary style made popular in the Machzor Mesorat HaRav for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, presenting the Rav’s exceptional insights on tefilla as adapted from his writings, public lectures, and classes. The Rav’s brilliant commentary is complemented by an elegant presentation of the tefillot in the renowned tradition of Koren Publishers Jeruslaem, together with an eloquent English translation of the tefillot and an introduction to the work of the Rav by the esteemed Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. Edited by Dr. Arnold Lustiger and co-published by OU Press and Koren Publishers Jerusalem, this new siddur will become a staple for students of tefilla and devotees of the Rav.

After the phenomenal success of the Koren Sacks Siddur, also co-published by OU Press and Koren Publishers Jerusalem, why is there any need for another siddur? If the Koren Sacks Siddur is the siddur for a new generation¸ is the Koren Mesorat HaRav Siddur the siddur for an old generation? The answer is simple—the two siddurim are complementary. The Koren Sacks Siddur is a usable and inspirational siddur with the commentary of Rabbi Sacks and the Koren Mesorat HaRav Siddur presents the penetrating depth of the Rav in an equally usable and inspirational format. Every synagogue and home should have both siddurim, offering users the opportunity to gain from both commentaries.

Here are some highlights of the Koren Mesorat HaRav Siddur:

- Commentary – Hundreds of insights collected from the Rav’s writings, recorded lectures and students’ notes, some appearing in print here for the first time

- Hanhagot – Lists and explanations of the Rav’s practices during prayer

- Translation – Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ acclaimed translation of the Siddur

- Typesetting – Koren’s clear and aesthetically pleasing fonts and intuitive layout

- Introduction – Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ new introduction to the Rav’s thought

- Paper – Special Bible Paper that is thin but strong.

Coming Winter 2010. More information available at www.OUPress.org

Excerpt from Commentary

Amida – In the Amida, man approaches God, pleads with Him and engages Him in dialogue. Human beings have many deficiencies, wants and aspirations; as a result, they knock on the gates of Heaven and present themselves before God, asking that He listen to their requests. God has singled out man by giving him the right to approach Him in this way.

Yet, the very institution of prayer is enigmatic. How can man possibly knock on God’s door, as it were? Who is man to appear before the Universal King and list his petty, insignificant needs? Would we dare act in this way before a king of flesh and blood? We cannot proceed unless we address this paradox. The first paragraph of the Amida confronts this daunting challenge.

But another obstacle is in our path at the very outset of our endeavor. On his own, it is impossible for man to comprehend his needs and formulate them in a lucid prayer. His mouth is inarticulate, his tongue falters. He requires Divine assistance not only for his sustenance, but also to recognize his deficiencies and to arrange his words. Man is dependent on God not only to fulfill his needs, but even to recognize and express them. And so, the Amida opens with the introductory phrase, “ה’ שפתי תפתח – O Lord, open my lips.” We cannot contemplate prayer unless we seek God’s assistance in formulating our entreaties.

We are abject, but beseeching God’s assistance in articulating our thoughts and words is not sufficient. Protocol must be observed. Mortal man, puny and insignificant, must first ask permission before engaging in a dialogue with the Infinite. Man needs a license, a matir. This critical element in the drama of prayer is provided by the first paragraph of the Amida. Containing no mention of our petty needs or mundane concerns, it is a blessing of the Almighty and an acknowledgement of His grandeur – an introduction which serves as the matter, the humble request for license which allows us to proceed to the gates of prayer.

The formulation of the berakha in the initial paragraph of the Amida, “בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹקֵינוּ וֵאלֹקֵי אֲבוֹתֵינוּ — Blessed are You, Hashem, our God and the God of our forefathers,” is strikingly unique. The typical introductory statement in a berakaha does not refer to our forefathers but contains the words “מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, King of the universe.” These words are omitted here, for how can temporal, flesh and blood man purport to approach the Eternal and Infinite King of the universe for fulfillment of his personal needs? Invoking the King of the universe in the beginning of the Amida would negate our very ability to approach God in prayer. Instead of “מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, King of the universe,” we invoke “אלֹקֵי אֲבוֹתֵינוּ, God of our forefathers.” If we are able to engage in prayer at all, it is only through the precedent of our forefathers who, as stated by the Gemara in Berakhot (26b), established the very institution of prayer.

Relying on the precedent of our forefathers in our initial approach to God is essential, but more is required of us. The Gemara in Berakhot (32b) states that one must glorify God prior to making requests of Him, a lesson learned from Moses as he entreated God to allow him entry into Israel (Deuteronomy 3:24). Yet, here we face a paradox similar to that presented above: how can lowly man purport to praise the Infinite God? Any possible description in man’s vocabulary would be woefully inadequate. Here too, precedent comes to our aid, and we limit our praise to the terse formula, “הָקֵל הַגָּדוֹל הַגִּבּוֹר וְהַנּוֹרָא, The great, mighty and awesome God.” Our praise takes this form because Moses himself used precisely these terms when praising God (Deuteronomy 10:17). Once again, without historical precedent, we would be unable to engage in such praise.

By the end of the first paragraph of the Amida, armed with the precedent of the Patriarchs’ prayer and Moses’ praise, the Jew can summon the courage to address God as “King.” The appellation “King” which was omitted from the initial part of the berakha appears at the end of the berakha in the phrase, “מֶלֶךְ עוֹזֵר וּמוֹשִׁיעַ וּמָגֵן, King, Helper, Savior, Shield.” Rather than describing a sovereign King who is distant and unapproachable, the emphasis here is on a King who is close and concerned, who has the desire and ability to help us and grant salvation.

More information is available at www.OUPress.org

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.