Pepsi. Cheerios. Verizon. Apple. Google. Mustang. Tropicana.

Have you ever wondered how brand names come to be? I imagine that hours, days, weeks or even months are dedicated to choosing a winning one. Is the decision made by a committee? Perhaps, but at its root, that decision stems from a stroke of inspiration, even a stroke of genius, in the mind of one person: the person who offered that brand name for consideration.

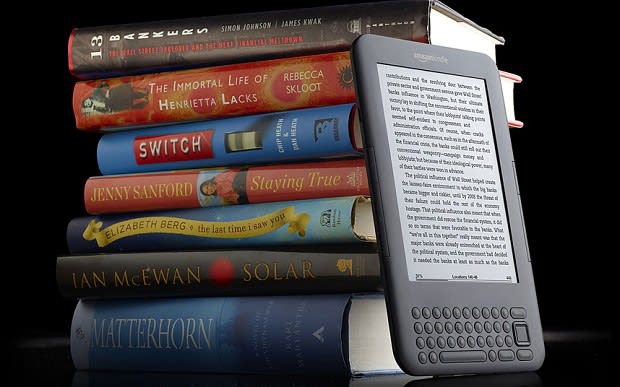

A cutting-edge electronic device has caught my eye and captured my imagination. But what fascinates me is not only the device itself, but the brand name by which it is known.

The product is an electronic book reader, and it is a marvel. Eight inches tall, five inches wide and no thicker than a pencil (just over 1/3 of an inch), it has the potential to contain over 1,500 books.

Stacked together, those books could weigh upwards of two thousand pounds. The electronic book reader weighs 10.2 ounces.

And did I mention that, in most cases, it can read your book to you?

Prior to its release, acquiring books entailed a time-consuming trip to one, and conceivably many, book stores — or at least an online shopping spree, followed by a waiting period until those books arrived at one’s doorstep. The technology associated with this product delivers a book to the electronic reader wirelessly, no matter where it is, in less than 60 seconds.

Downright amazing. But what really takes my breath away is the name that Amazon.com has bestowed upon its electronic book reader: the Kindle. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary offers definitions of kindle that evoke layer upon layer of reverence for the magic of reading:

transitive verb:

to start (a fire) burning : to light : to stir up : to arouse : to bring into being : to start : to cause to glow : to illuminate

intransitive verb:

to catch fire : to flare up : to become animated : to become illuminated

The significance of this device’s brand name is as inspired as it is profound: At a time when the thrill of reading has been anesthetized by the lure of television, DVDs and video games, the only antidote is to light a fire within us, to arouse interest within us, to implant a glow within us for the joy of books.

Which brings me to my father, of blessed memory, and the sheer joy he derived from books, the Good Book in particular. Were he with us today, he would examine this newfangled invention through a decidedly Jewish lens. If I close my eyes, I can hear his voice and see the twinkle in his eyes as he’d invoke his favorite joke, “The Elephant and the Jewish Question”:

Four doctoral students — a German, a Frenchman, a Russian and a Jew — took a seminar requiring a paper about elephants. The German wrote about authority in elephant society. The Frenchman wrote about the love life of the elephant. The Russian wrote about sharing among elephants. And the Jew wrote about the elephant and the Jewish question.

Like my father and the Jewish doctoral student, a Chasidic master living at the turn of the 20th century looked at the world around him with an eye to Jewish life. One day, a disciple approached him and asked, “Rebbe, every time I turn around, I hear about new, modern devices in the world. Tell me, please, are they good or bad for us?”

“What kind of devices?” asked the Rebbe.

“Let me see. There’s the telegraph, there’s the telephone, and there’s the locomotive.”

The Rebbe replied, “All of them can be good if we learn the right lessons from them. From the telegraph, we learn to measure our words; if used indiscriminately, we will have to pay dearly. From the telephone, we learn that whatever you say here is heard there. From the locomotive, we learn that every second counts, and if we don’t use each one wisely, we may not reach our destination in life.”

So, what can we learn from the Kindle? Like the telegraph, telephone and locomotive, it offers us lessons – as I see it, at least three of them – for living life meaningfully.

Function: The Kindle’s inner workings remain a mystery for most of us, but when viewed from the outside, it functions seamlessly. A keystroke, and something appears where before there was nothing. Similarly, the inner workings of our planet are shrouded in mystery. And yet, year in and year out, we on the outside see flowers, fruits, vegetables and grain emerge from it. But there’s a catch: If no one strikes a key, nothing will appear on the Kindle’s surface, and if no one lifts a finger, the Earth’s surface will be barren. As the great commentator Rashi elucidates, when the Torah concludes its narrative of the world’s creation with the words, “And God blessed the seventh day, and hallowed it; because on it He rested from all His work which God created to do” (Genesis 2:3), the seemingly superfluous verb “to do” alludes to humanity’s responsibility to interact with and tend God’s world.

And can’t the same be said for our soul? Its inner workings are ineffable. Its potential is limitless. But left fallow, it will flounder.

Content: Imagine receiving a Kindle as a gift from your father. Now picture three separate scenarios:

Scenario #1: Several months later, he asks you if you like it. You hesitate to answer. How can you tell him that it’s been sitting in its box, unused, devoid of content?

Scenario #2: Several months later, he sees you using it. You see him beaming with delight — until he notices that you’re reading some insipid, platitude- or gossip-filled book.

Scenario #3: Several months later, you take him out to dinner for the express purpose of thanking him for his gift and the meaningful, scintillating material to which it has introduced you.

The spiritual parallel is obvious. Granted the gift of life, what do we fill it with? Nothing? Junk? Or purpose?

Name: The way I see it, the people charged with selecting the Kindle’s name could have called it “Fireworks” or “Spotlight” or “Starburst.” But they didn’t. Shunning fanfare and bravado, they opted for understatement. To coax an honored but faltering pastime back to life, it pays to be gentle. Start with an ember. As it glows, it will grow.

To coax an honored but faltering legacy back to life, it pays to be gentle — and patient. We are its heirs, and no matter where we stand on the spiritual continuum, we deserve nothing less. If each of us starts with an ember, we will illuminate the world.

Chava Willig Levy is a New York-based writer, editor and lecturer who zips around in a motorized wheelchair and communicates about the quality and meaning of life. Currently writing her memoir, A Life Not With Standing, she is available for speaking engagements and can be reached via her web site: www.chavawilliglevy.com.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.