You and I know what it’s like, because we’re both human: the sense of innocence, and of having been wronged. The keen desire to craft some put-down that will diminish the other person as he has diminished us, to put him back down and ourselves back up; to restore our dignity as it must be restored, as we deserve to have it restored. The rising indignation; the festering of our wound in silence; the self-righteousness that builds up within. The suppression of our cutting retort, or, alternatively, just really letting this person have what’s coming to him.

How good it feels to be so strong…until our conscience speaks up. Then we must defend ourselves. There’s guilt, or embarrassment, or shame over how we’ve behaved, and all the external consequences that are already out of our hands: the reactions of those upon whom we’ve vented our spleen. If we love them, it’s hard to bear the distance that has suddenly opened up a chasm between us.

Then there’s the loss of self-respect, which always, without fail, results from any loss of self-control.

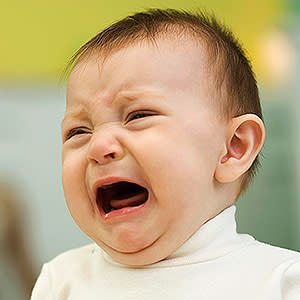

It’s that ancient infant within us, our anger, in all its many manifestations as they vary from individual to individual. And as on so many other occasions, it has gotten the better of us once again. Anyone who has ever had parents, or children, or friends and relatives and neighbors, or co-workers, bosses, employees…in other words, as anyone who has ever been a human being knows, life unceasingly provides very good reasons to get angry, and the reason for this is obvious: the world has a way of not coinciding with our wishes. Therefore, when crossing paths with anyone or anything on the planet, including ourselves, there’s a good chance we’ll experience some frustration of our will.

How should this reality of life be dealt with? Sometimes, it seems the only answer is to make people and things do what you want. One’s children often fall into this category. Most of us, however, eventually discover that in spite of its strong appeal, this solution leaves something to be desired — mainly, that it doesn’t work.

I will never forget my own moment of realization in this regard. One day early on in my motherhood, sinking down onto the couch after an afternoon spent yelling at my innocent little kids, something dawned upon me: it’s hard work, getting angry. And in the next few moments, two new ideas hit me:

- Being forced to do anything runs against the grain of human nature, even if the person in question is only two-and-a-half.

- If I find myself trying to control any other human being, that’s a reliable sign that I’ve lost control of myself.

These realizations touched me so profoundly that my anger vanished into thin air and I remained imperturbable for the rest of that day. But when, by the following afternoon, I was once again tired and bored and feeling isolated, I had to start all over again from scratch. Like most abrupt awakenings, this one may have had a significant impact upon my general level of understanding, but its effect on my behavior was transient.

We may be appalled by the destructiveness of our anger on ourselves and on those who are important to us. We may understand very well that old saying, anger is like acid, it destroys the vessel that contains it. We can even have tasted the bitter truth in the double meaning of that word mad. Losing one’s temper is akin to losing one’s mind. But the middah of anger can only be changed by conscious long-term effort to control one’s speech, until self-restraint becomes habitual. To achieve that goal, what is required, above all, is a modification of our basic beliefs about life itself.

* * *

Rosh Hashanah is the one day of the year dedicated to the principle that G-d is King of the universe. The holiday’s chief goal is that by the end of the day, we will not only have tasted a number of apples dipped in honey but will also have arrived at the recognition, on some level, of the fact that Hashem is truly – that means actually – the source of all events. G-d is here, as I type. G-d is with you as you read, as your eyes take in these words. The sounds you hear out the window, the memory in your mind of what happened this morning, the fragment of memory that appears instantaneously in your utterly miraculous computer of a mind when you see the phrases: the house I grew up in, or 1975, or white curtains, or Afghanistan. Your breath, the one you’ve just taken, and the one you’re about to take. The child in Botswana crying for his mother and the Israeli government that’s about to collapse, the birth at this moment of a star seventy million light years away…An underlying recognition of the totality of the Creator’s presence is the necessary foundation for whatever truthful self-examination we engage in during the Ten Days of Repentance, because if we carry within us an awareness that G-d is the Source at the center of all phenomena, those that loom large and those that appear trivial, those that are earth-shaking and those that seem unimportant, then everything’s cast in a different light.

When such an awareness prevails, we’re less inclined to get mad at the children for fighting during dinner, or to retaliate at so-and-so for her snide remark, or to get upset when stuck in a traffic jam.

Although anger can quite literally destroy us, it isn’t an enemy to be crushed and banished. It’s an intrinsic facet of our personalities. It’s purposefully programmed into us and it need not, cannot be denied. It can provide us with superb insight into our own usually hidden selves. What is it that irritates, annoys, infuriates us? The more developed our capacity to identify truthfully what’s really bothering us, and to recognize that the real object of our anger always lies within, not in anyone else or any external phenomenon, then the better our chances of becoming our own masters. Anger, which can work so powerfully against our happiness, is the very tool we’ve been given to get a handle on our invisible, elusive inner selves. What aggravates me? What inflames me? The more truthful our answers, the brighter the illumination of what makes us tick. It’s precisely in the struggle to get control over that in ourselves which seems uncontrollable, that we have a chance of becoming who we are meant to be. Rav Moshe Feinstein was once asked how he could possibly stay as calm as he did in the face of intense provocation. “Do you think I was always like this?” Rav Feinstein replied. “By nature, I have a fierce temper, but I have worked to overcome it.”

It’s uncontrolled anger that brings murder and war to mankind, anger that dissolves marriages and makes for unhappy childhoods; anger, in general, that drains life of its joy and shatters a person’s self-respect. If someone were to wave a magic wand and offer to free us of this internal scourge once and for all, who among us wouldn’t jump at the chance? But by the same token, who among us finds anger easy to let go? As attractive a proposition as it may seem on paper, letting go of it feels like a sacrifice. It’s very difficult to relinquish the belief that we know what’s happening, and why, and that if I’m suffering, then something or someone is responsible for it.

The world is larger than I think, and the causes behind all things infinitely more mysterious than my mind can grasp. May we look fearlessly into the mirror, and open our hearts to a world we can’t control.

This piece is excerpted from “A Gift Passed Along” and reprinted with the author’s permission.

Sarah Shapiro’s most recent books are “A Gift Passed Along,” and “The Mother in Our Lives” She writes for a number of publications in Israel and the United States, and teaches writing in Jerusalem, where she lives with her family.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.