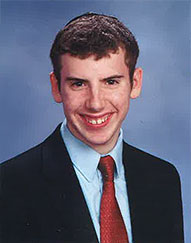

Meet Eli Gorelik, the twenty-three-year-old gabbai whom Tifereth Israel’s 200-member congregation has come to respect and rely upon. He’s likely one of the youngest gabbaim in the world.

He’s also probably the only one with autism.

“He has his routines,” says Yosef Avrahami, another gabbai (there are five in total) at the Passaic, New Jersey shul and a member there for close to four decades.

Eli developed normally for the first two years of his life; at fourteen months, he was walking and talking and freely interacting with those around him. Then things began to change.

“He wasn’t interested in other people,” Jacki says. “He was in his own world.” His preschool teacher reported that during circle time Eli would turn to face outside the circle. Eventually, he was diagnosed with autism.

Autism is the most common condition in a group of developmental disorders known as the autism spectrum disorders, and is characterized by varying degrees of impairment in sensory processing, speech and language development, social interaction and communication skills. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that one out of 160 children in the country currently has autism.

Typical of children with autism, Eli demonstrated markedly rigid behavior. “If I didn’t have a bagel and cheese ready for him when he came home from preschool, he’d ‘lose it,’” says Jacki. “I couldn’t take him anywhere; he would fixate on the movement of the escalator or run back repeatedly to push the elevator buttons so he could watch the doors open and close.” The Goreliks’ other children noticed their brother was different. “It was tough [for them]; he was doing inappropriate things, like talking to himself, and he had problems communicating with others,” says Rabbi David Gorelik, Eli’s father, a rabbinic coordinator at the Orthodox Union (OU). “Once my older son asked why Hashem made Eli the way He did,” says Rabbi Gorelik. “I told him: ‘Hashem wanted us to do chesed for Eli.’”

The Goreliks enrolled Eli in a special program for children with developmental disabilities, where his responsiveness improved. “His world capacity is limited,” says Rabbi Gorelik. “Whereas you and I can talk about things outside of our experience, his interest lies solely in his own world.”

There’s No Place Like . . . Shul

When Eli was five, his father began taking him to Tifereth Israel, and shul quickly became the center of his world. “He loved it,” says Rabbi Gorelik. “He would sit through the rabbi’s sermon without making a sound.” Eli chose to occupy the chair on the pulpit, next to the rabbi. “Every time the rabbi finished his sermon, he’d run to shake his hand and say, ‘yasher koach!’” says Rabbi Gorelik. A shul member expressed his chagrin that “a child with autism [gives] the rabbi a yasher koach, when none of the others at the dais do,’” relates Rabbi Gorelik. “From then on, [everyone] began offering the rabbi yasher koach.”

As a young child, Eli would sit in his seat without participating in the service, his eyes following the rabbi’s every move. Over time, he became more involved. “Suddenly, I heard him saying Shema along with me,” says Rabbi Solomon Weinberger, who served as rabbi of the shul for more than four decades and is currently the rabbi emeritus. “And when I stood up for Shemoneh Esrei, he got up and stood next to me and bowed every time I bowed and shuckled [swayed] with me.”

Eli promptly picked up every word of the Shabbat davening. He even recited Kaddish Derabbanan with Rabbi Weinberger. “I had the only kid in town who was saying Kaddish for his parents while they were still alive,” jokes Eli’s mom. “It never fazed the rabbi; he has such love for every individual, and Eli grabbed onto it.”

“He seemed to gravitate to me and I enjoyed his friendship,” says Rabbi Weinberger. “The very fact that he was able to [come to] the pulpit and to stand next to the rabbi gave him a sense of importance, a feeling that he is wanted and cherished.”

When Eli turned eight, his parents informed him that it was time for him to sit with the rest of the congregation. Along with maturity came a sense of responsibility; he slowly began taking on the duties of a gabbai. One Shabbat around ten years ago, Avrahami says, when he approached the bimah, Eli started following him and participating in the preparation for the Torah reading. He’s been doing so ever since.

Eli’s mother attributes his high level of comfort with davening to Rabbi Weinberger’s magnanimity and the openness of congregants who followed the rabbi’s lead. Harry Fruhman, a former member of Tifereth Israel, made an immediate and meaningful connection with his young shul mate. It didn’t hurt that he was the congregation’s “candy man.” As Eli started coming to him for some goodies, Fruhman urged him to sit beside him; that ultimately became Eli’s official seat. “I would take his hand and use his finger to point to the places in the siddur to daven,” he says. Eli kept returning, and not always for the candy. “I’d offer him a lollipop,” says Fruhman. “He’d say ‘no’ and stick his finger out for me to show him where to daven. At Keriat haTorah, no matter where he was [in the sanctuary], he’d come running to me [so I could move] his finger to the place in the parashah.”

Over the years, Eli’s role in the shul has expanded—he is now also the official proofreader of the shul calendar. “He’s always been intrigued by calendars and has the eye to notice inconsistencies,” says his father. “On [last year’s] Rosh Hashanah schedule, he found a number of mistakes. He pointed out to me that Minchah should have been listed as 7:00 rather than 7:20. He also noticed that the hashkamah minyan wasn’t mentioned.” Now, each month, the shul sends Eli a draft of the calendar to proofread.

When Eli’s not in Passaic for Shabbat, he’s at a Yachad/National Jewish Council for Disabilities (NJCD) Shabbaton offering his inimitable help. Yachad/NJCD is the OU’s program dedicated to enhancing life for individuals with disabilities. “A lot of details, planning and strategizing go into a Yachad Shabbaton; it is possible to forget something,” says Naftali Herrmann, director of community outreach and engagement at Yachad. “The staff is comforted by the thought that if we forgot anything . . . Eli’ll be the first to realize it and let us know.”

“[At the Shabbatonim,] he was always the first one at Shacharit every morning,” says Herrmann. “If I came to shul late, he would point to his watch to let me know.”

Fruhman also notes the importance attending services holds for Eli. “One should never underestimate how meaningful davening is to children with special needs,” he says. “You might not think they are internalizing—unequivocally, they are.”

Rabbi Aaron Cohen, the current rabbi of Tifereth Israel, concurs. “When Eli gets an aliyah it gives him an [obvious] sense of pride,” he says. “His very strong connection to Torah and mitzvot makes an impact on the congregants.” And he makes sure Eli is cognizant of it. “It’s important that the rav has a personal relationship with children with special needs to demonstrate to them that they really matter and that they are an integral part of the shul,” he says. “When Eli is away for Shabbos, we’ll let him know we missed him.”

“[Eli] does the maximum to participate and has developed friendships with many congregants,” says Rabbi Cohen. “This sets the tone in the shul, showing that we care about each person.”

The community has also benefited from actively reaching out and embracing Eli. “He has taught us all humility, empathy, patience and [about having] a sense of humor,” says Jacki. “A child with special needs shows you what’s important, and what is not; he shows you how to extend yourself in order to understand and appreciate the value and blessing of every human being.”

When it comes to integrating individuals with special needs, Tifereth Israel’s congregation is a true model. “They’ve known Eli now for [more than] thirteen years,” says Jacki. “It’s rewarding to see how he’s developed and to watch him running out of the house and down the street to get to shul.”

Eli makes a point to leave home extra early, eager to take his rightful place in the congregation. For that, his family feels immeasurable hakarat hatov. “I thank my fellow congregants and both rabbis for having been so good to him; they’ve accepted him and treat him like anybody else. They look at him as another shul member.”

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.