An Interview with Ruchama King Feuerman

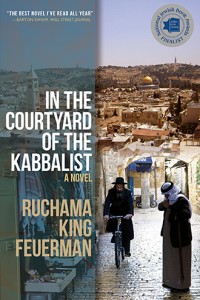

Ruchama King Feuerman is the author of In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist, which was published by the New York Review of Books to critical acclaim. She lives in Passaic, NJ, with her husband, Simon Yisrael Feuerman, a psychotherapist and essayist, and their four children. Her first novel, Seven Blessings, was partially inspired by the year she spent living in the house of a matchmaker in Israel. Feuerman moved to Israel when she was 17 and returned to America ten years later to earn a Masters in Fine Art at Brooklyn College. The beguiling In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist tells the story of Isaac Markowitz, an eczema-riddled, middle-aged haberdasher, and his friendship with Mustafa, an Arab who works as a janitor on the Temple Mount. Together they uncover a plot to destroy the Jewish history of the land of Israel.

Ruchama King Feuerman is the author of In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist, which was published by the New York Review of Books to critical acclaim. She lives in Passaic, NJ, with her husband, Simon Yisrael Feuerman, a psychotherapist and essayist, and their four children. Her first novel, Seven Blessings, was partially inspired by the year she spent living in the house of a matchmaker in Israel. Feuerman moved to Israel when she was 17 and returned to America ten years later to earn a Masters in Fine Art at Brooklyn College. The beguiling In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist tells the story of Isaac Markowitz, an eczema-riddled, middle-aged haberdasher, and his friendship with Mustafa, an Arab who works as a janitor on the Temple Mount. Together they uncover a plot to destroy the Jewish history of the land of Israel.

Q: Was it difficult leaving Israel?

A: I remember my last day there, I felt like my stomach was getting ripped out of me. I’ll put it this way: In Israel whenever I got in someone’s daled amos, their four cubits of space, I could almost hear a song under the breath. There was this uplift, this musicality that was thrumming through Israeli life. When I came to America it felt a lot saner but there was just so much less beauty. I didn’t feel that underlying spiritual bass rhythm.

Q: Both your main characters seem flawed. What is it that attracted you to write about them?

A: I think that, if I’m honest, I’m very attracted to writing about failed men. Men who are on the verge; Isaac is the almost person: he almost became a rabbi; he almost married the woman of his dreams; he almost started a yeshiva. [I’m interested in] people who strive but are not quite there. People who are successful don’t always strike me as interesting. They’re not in a state of yearning because often a person who is successful has already arrived, at least in his or her own mind, and so they’re just boring to me, fairly or not.

That’s why I’m also attracted to singles, especially older singles. They’re in limbo, not there yet, whatever ‘there’ means. With a younger man, if the woman he’s dating doesn’t seem compatible, he can always change the channel; go out with someone else. But when you’re older you can’t so easily keep telling yourself: wrong person, wrong person. You have to start looking within. In general, I find the motif of matchmaking irresistible. It’s so much more than guy meets girl, especially when it’s overlaid within a frum framework. It’s lineage meets lineage, destiny meets destiny. So much depth and drama are staked on these outcomes.

The biographical antecedents to these characters are probably my father. He was talented in all these areas: composing songs, painting, writing, dance, storytelling, a great conversationalist, but he was somebody who was an assistant in a blueprinting shop. My father’s lack of success weighed heavily on me as a child and it pained me. That’s something that’s imprinted itself on me in the men I write about. In a funny way Mustafa and the Isaac character are twins of my father. Of course I had no idea of these layers when I wrote the book. If I had, I probably would’ve dropped it cold. I do find it takes me a couple of years to really understand why I wrote a book and what it’s really about.

Q: How has the reaction been to the novel in Jewish circles?

A: I get a real kick that Jews of such different stripes are gravitating toward the book — say, a rebbe in a Yeshiva on the one hand, or an ultra Reconstructionist synagogue on the other that decided to adopt the book for its One Book, One Community Read. A rabbi from my seminary days noted how impressed he was that I was able to show romance in such a clean way. And yet, even though there is no kissing or anything, the tone of it makes it an adult book. I always say, read it first, and then decide if you can share it with your kid.

Sometimes I get people who are annoyed at me for having depicted a sympathetic Arab character. Then there are people who think I depicted Arab society way too harshly. I’ve been trying to develop hippo skin, to not get undone by the praise or the nitpicky complaints, like the Hasidic woman who said, ‘Why did you have to make the Hassidic teen’s face purple with acne?’ She was joking, I think.

Q: You’re Orthodox and a good writer, given the state of fiction in Jewish bookstores that seems to be a dearth of good Orthodox writing.

A: What’s happening in the Yeshivish world of writing is actually exciting. You know how in the yeshivas, they throw so many boys at the Gemara text, a few stars are bound to emerge? Same here. Walk into any Jewish book store and you’ll see tons of novels, serials, short story collections that speak to a Yeshivish reality. A few are really wonderful. My beef is it’s not happening in the Modern Orthodox world, not by a long shot. Walk into any Jewish book store and you’ll see. Or actually you won’t see fiction written from a Modern Orthodox or Centrist perspective. If you do, it’s either coming from Israel or written from a sour perspective; you don’t find the authentic fiction that reflects the richness of a modern Orthodox life, with its beauty and blemishes. I think in the yeshivish world you have a captive audience: they’re not likely to read anything else out there so you’ve got a cottage industry of people wanting to read about themselves. Modern Orthodox aren’t as limited. The whole world is their library. That’s great, on the one hand. But so few will bother to write fiction.

I’m upset that Jewish Action does not publish fiction. If not them, then who will? They should run contests with real monetary incentive. Believe me, the writers who supposedly don’t exist will come out of the woodwork. Because If we don’t encourage [writing], you’re going to keep on getting sour work written by defectors or those written by people who mainly want to expose the hypocrisy of the system. What is the Modern Orthodox kid going to be reading on Shabbat? He’s not going to be reading about a kollel life or the drama of a Lakewood shidduch gone awry. It’s simple. If you don’t create literature about your own world you’re not serious about preserving that world.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.