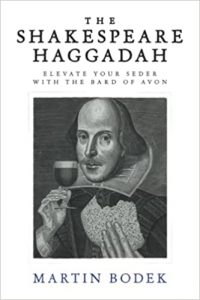

The Shakespeare Haggadah

The Shakespeare Haggadah

Martin Bodek

200 pages

Post Hill Press, 2022

A few years ago, I reviewed Martin Bodek’s first Haggadah, The Emoji Haggadah. Written completely (and I do mean “completely!”) in emojis, I found the book to be impressive in that he could actually accomplish such a feat, as well as a fun and challenging puzzle to be unraveled. It wasn’t much use as an actual Haggadah, though – at least not for anyone born in the 20th century. (I have no idea whether a 14- or 15-year-old could effortlessly translate emoji to English, let alone Hebrew!)

Since then, Bodek released two more Haggados – The Festivus Haggadah (based on the fictional holiday from the television show Seinfeld) and The Coronavirus Haggadah (based on some recent events about which you might have heard). I haven’t seen either of these but based on the author’s own words, they’re intended more for entertainment than for actual seder use.

In this, Bodek’s fourth Haggadah is different. Not only is The Shakespeare Haggadah entertaining, one can also use it to lead (or follow) one’s seder with pages in the traditional Hebrew facing those in English.

Let’s discuss the language. The Shakespeare Haggadah isn’t just a Haggadah written in Elizabethan English; it actually takes a deep dive into Shakespeare’s plays. And I don’t mean just Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet and the Scottish play (hameivin yavin), I mean Titus Andronicus, Cymbaline and Troilus and Cressida – you know, the stuff they never taught us in high school.

The English side is replete with quotes from, and references to, Shakespeare’s plays. For example, among the items on the seder plate we find “The bare-picked bone of majesty” (King John, Act 4, Scene 3), “Roasted egg in wrath and fire” (Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2) and “The enchanted herbs” (The Merchant of Venice, Act 5, Scene 1). Similarly, the four sons are described as “one [who he is] wise,” “one who hath kept an evil diet long,” “one who is as innocent as grace itself” and “one who doth not knoweth what’s best to asketh.” (I’ll let you look up those sources yourself.) The way that Bodek has found so much relevant imagery is at least as impressive as the effort involved in translating the Haggadah into emojis, perhaps moreso!

But that’s not all! While Bodek, true to form, goes all in on the Elizabethan English from the copyright notice to the back cover, there is one exception: the book includes humorous “stage directions” written in modern English. As something of a meta-joke, the stage directions are reverse-engineered into the Hebrew pages as a complement to the traditional text.

Not only that, the choice of font, at least so far as the English side is concerned, continues to support the book’s illusion of pedigree. Resembling something that might have rolled off of Benjamin Franklin’s printing press, the old-timey typeface conveys a message of antiquity without saying a word.

While Bodek takes these extra steps to simulate the feel of reading a Shakespearean play, he does stop short of employing iambic pentameter.

If there’s one quibble, it’s the authenticity of the grammar. For example, Bodek frequently employs “thee” (objective) where he should use “thou” (nominative), such as in the grammatically incorrect “Blessed art Thee.” Similarly, liberties are taken with the suffixes -eth and -est, which should only be used with third-person singular and second-person singular, respectively. However, if I might be permitted to paraphrase Shakespeare myself, “If it were so, it was not a grievous fault” (riffing on Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene 2). After all, there are plenty of books published in modern English that contain grammatical faux pas that nobody notices and about which nobody cares. (A personal bugaboo is “between you and I” but – fun fact – even Shakespeare himself turns that phrase in The Merchant of Venice.) So unless you’re a real nitpicky grammar type, you probably won’t notice, let alone care.

In case you missed it, I am a real nitpicky grammar type, but I still enjoyed this book. It’s absolutely delightful and I may actually use it at the seder this year rather than the Maxwell House Haggados that our ancestors used in the land of Egypt. At the very least, I will pass it around and encourage people to read some of the English sections aloud. It’s a must for Haggadah collectors and a treat for Shakespeare fans. Even if you fall into neither category, it’s a unique experience and a fun read.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.