On Shabbat, Parashat Balak, July 20, Jews all over the world will be one step closer to completing the thirteenth cycle of the Babylonian Talmud by completing tractate Erchin in the Daf Yomi cycle. We are all familiar with Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who initiated this worldwide phenomenon–but does anyone ever think of Daniel Bomberg, the Christian who literally put the “daf” in Daf Yomi?

Rabbi Shapiro’s brainchild was born in 1923, a time much like our own. As powerful political, social and economic forces exerted a centrifugal force on the Jews of that era, Rabbi Shapiro understood that the shared study of the Talmud, a core Jewish text, was a powerful way of bringing the fractured Jewish people together under the umbrella of our long intellectual and spiritual tradition. Since then, his innovative program, as boldly ambitious as it was elegantly simple, has united Talmud enthusiasts from Lakewood to London, from Hebron to Hong Kong–literally anywhere in the world, one can find a class that is literally keeping Jews around the world on the same Talmudic page, every single day. Rabbi Shapiro’s brilliant idea, however, could not have occurred without the signal contribution of one Daniel Bomberg.

Born in Antwerp in the late 1400s to a middle-class family of printers, Bomberg received a decent liberal arts education that even included a smattering of Hebrew. This served him in good stead when he went to make his fortune in the bustling metropolis of renaissance Venice, home to a mercantile Jewish population that was recently restricted to the Ghetto.

Printing was in its infancy, but Jews were among the early adopters of this disruptive new technology. The Soncino family were producing beautiful editions of individual Talmudic tractates, confident that the lower production costs of printed Judaica would place books in the reach of average families. Known for their scholarship, the Soncinos took great pains to produce works of lasting quality—but they simply couldn’t print their tractates fast enough to meet the demand.

This is where Bomberg saw his opportunity. Assembling a group of Jewish scholars, beginning with Jews who had converted to Christianity, Bomberg rapidly churned out printed versions of Jewish classics such as the encyclopedic Mikra’ot Gedolot edition of the Torah. The early editions were plagued with errors, and many readers resented the use of apostates in their preparation, but Bomberg had accurately judged the market: the people of the Book wanted lots more books, especially the Talmud, and the demand far outpaced the leisurely supply of the Soncino family of printers.

Bomberg soon replaced his early staff of Jewish Christians with well-regarded Rabbinic scholars straight out of the ghetto. As a Christian, he was also able to negotiate favorable terms for his business, including the right for minimal Church censorship, arguing that ancient texts required preservation in their original state. He even secured rare privileges for his Jewish staff, such as an exemption from the requirement to wear the humiliating Jewish hat.

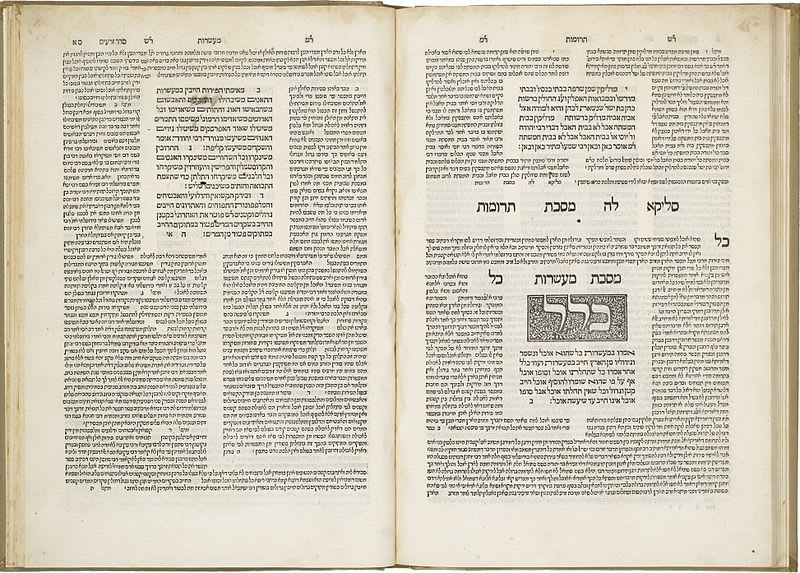

In a spurt of remarkable productivity, the Bomberg printing house produced a fantastic number of Hebrew books, including the first full printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud. He shamelessly copied the Soncino design, with the commentary of Rashi on the side closest to the spine and Tosafot on the outside of the page, and added many innovations of his own, including one especially important change: page numbers.

Yes, page numbers. As text-oriented as Jews are, we simply never got around to inventing basic pagination (we also lagged behind in punctuation, and as anyone who struggled to learn modern Hebrew knows, we weren’t so hot at vowels, either). Looking at the rapidly evolving conventions of 15th-century printing, Bomberg added a letter “bet” to the first page of text in Tractate Berakhot of his second edition of the Talmud—and the Daf was born.

Since then, much rabbinic and scholarly ink has been spilled in vain, struggling to understand why he didn’t begin with “aleph,” the first letter of the alphabet. The simple explanation is that Bomberg considered the title page as the first folio, or page one.

Although it seems obvious in retrospect, Bomberg’s brilliant introduction of page numbers ultimately set the standard for every single Daf in virtually every single printed edition of Talmud for the next half-millennium. If a given word is on a Bomberg page, it should be on the same page in every future Talmud. Future printers adopted this standardized allocation of precise passages to every page, and there was no messing with Bomberg: even the great contemporary scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz was roundly excoriated in certain circles for altering the traditional page layout in his award-winning edition of the Talmud.

Yet by standardizing the Daf, Bomberg made possible the notion of an international, coordinated study of the Talmud. Rabbi Shapiro literally couldn’t have done it without him.

There’s one basic takeaway message to this story: when tens of thousands of Jews crowd together in January 2020 to celebrate another cycle of Daf Yomi—last cycle, nearly 100,000 Talmudists packed Met Life stadium, and this cycle will likely be bigger—we should recall not only the phenomenal dedication of the Daf Yomi students and teachers, and not only the inspirational message of unity through study proposed by Rabbi Shapiro’s vision, but maybe we should give some credit to the blessing of a philosemitic Christian from Antwerp, Daniel Bomberg.

Dr. Henry Abramson serves as a Dean of Touro College. He is the author of the Jewish History in Daf Yomi podcast, part of the OU Daf Yomi Initiative.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.