We all want to change our bad habits into good and productive behaviors. Whether we are dealing with habits that affect our health, fitness, weight loss, or other poor habits, all of us want to reduce negatives and increase positives. But if you’ve attempted to change long-ingrained habits before, you know how utterly impossible it can seem at times. If you have tried to stop smoking, lose weight permanently, spend less time on your computer or mobile device, stop biting your nails or any other bad habit, you know that it is literally Kryias Yam Suf—practically impossible. Yet, there are those who succeed. If 5% of people who lose weight really keep it off, what is their secret? It might take many attempts, but people DO quit smoking. We need to look at what it is that is going on in our brains when things become ingrained behaviors and how we can undo years of poor behaviors.

The phone in my office rang yesterday with someone asking about information about our 10 week program. After I told this lady about how it works and I explained how we combine dietetics and exercise with behavioral change, she asked me about people who are addicted to specific foods. She mentioned that she is hooked on sugar and carbs and that is her main problem. She wanted to know if we had experience with situations like hers. I mentioned to her that we really need to take a close look at what is really going on. Is this truly food addiction or is it emotional eating like cravings or desires? Maybe it is just a mindfulness issue?

We like to place blame for our behaviors on outside factors. Your spouse should not have brought your favorite chocolate chip cookies into the house. You walked into the store and the cigarettes were prominently displayed behind the register, so you purchased them. “I can’t help it, I grew up this way”. But all of this comes down to the mechanisms through which the brain creates a behavior. This is something very complex but let’s take a look at a simplified explanation of what happens in the brain when it forms a habit.

Let’s make a change

Let’s say you decided after the Yomim Tovim that your goal this year was to lose 15 Kilo. You made up your mind that you were going to join a gym and work out there 4 times a week and walk outdoors another 3 times a week. Also, you would eat three times a day have 2 small snacks and not skip breakfast. Instead of going to sleep at midnight every night, you would turn in by 10:30. These are all great habits with admirable intentions. But if you keep the typical pattern, by 6 weeks later, you wouldn’t have been to the gym in 2 weeks, you’d be skipping breakfast and overeating at dinner, and you would be lucky to get to bed by 1 a.m. This pattern is all too familiar.

The problem lies in the processing systems of the brain and in the tug of war between two major systems that need to work together: the new brain and the old brain. The new brain is associated with the outer region of the brain (cerebral cortex) and the prefrontal cortex. Often termed as the conscious, rational part of the brain, the new brain helps us think critically, plan our next steps and learn behaviors (Miller & Cohen 2001).

The old brain is associated with the inner regions of the brain known as the limbic system and the basal ganglia. They are associated with emotional processing. The basal ganglia are responsible for remembering whether a behavior created a positive or negative response, which helps in determining whether we perform the behavior again or avoid it altogether.

The basal ganglia also stores behaviors. For example, it initially takes a lot of brainpower to learn how to drive a car with a manual gear. But as the behavior becomes learned, the basal ganglia store the response and we can drive a stick shift without having to consciously think about it, which allows us to divert our brain energy to other tasks. This is how the brain saves valuable energy (Yin & Knowlton 2006).

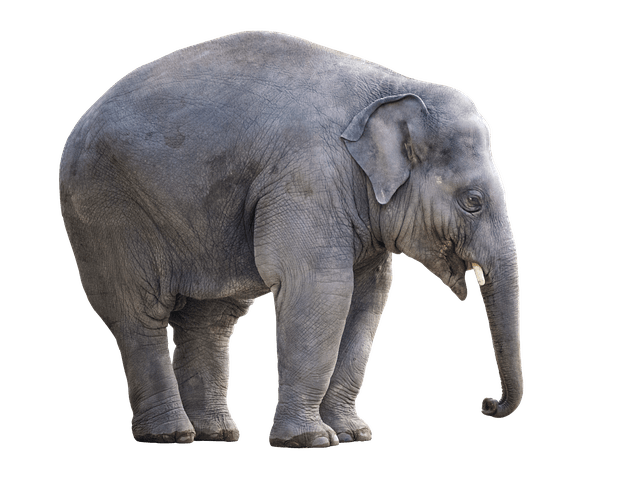

The Elephant

In his book about happiness, Jonathon Haidt uses the analogy of the old brain being a large, emotional elephant, and the new brain being the elephant’s rational rider (Haidt 2006). Picture the rider holding the elephant’s reins. As you probably know very well from experience, the “elephant” can override the “rider” any time it disagrees with him. For example, the elephant will fling itself into oncoming traffic to protect its calf. The rider might rationally recognize that jumping into traffic could lead to his death, but of course he has no say in the matter considering the size discrepancy between him and the elephant.

When it comes to making resolutions in order to change habits, the new brain plans out an exciting journey for creating a new you, and your old brain is willing to go along. But as you initiate the new behaviors, the old brain quickly realizes how cumbersome the process is, especially when the reward is minimal or nonexistent at the outset. For example, after your first workout, you’re sore for 3 days. The basal ganglia (old brain) stores the behavior as having a negative outcome, even though the prefrontal cortex (new brain) knows that soreness is part of the journey. The elephant overrides the rider, and soon you’re sleeping an extra hour instead of exercising. The two sides of your brain are not battling one against the other. Should I get up and go to the gym (the rider) or should I sleep later instead (the elephant). The elephant, or the part of your brain that store the old, ingrained habits almost always wins.

In order to win the battle

It’s not a matter of a 12 week program or 21 days to change one habit. The time it takes to change habits is very individual. Studies have shown that it can take some people up to 2 months or even more just to work on one behavior. In our clinic, even though we hear about ambitious goals, like losing a great deal of weight or getting off various medications, we have to reduce this into smaller and more realistic goals. For instance, losing a kilo at a time, adding 5 more minutes to the daily walk, putting in a couple minutes of muscle building exercise besides aerobics, or eliminating a poor food choices. Establishing milestones helps one manage expectations, which increases the likelihood that a new and better habit will form.

Another area we work on is motivation. Your doctor might have told you that if you don’t lose 9 or 10 kilograms, he will have to medicate you and that these medications might have undesirable side effects. That motivation might work well initially, but motivators that bring results are more intrinsic, or natural. Scare tactics are more extrinsic; that is something coming from outside. Losing weight may be intrinsically important to someone because they gain a sense of accomplishment, feel more self-confident, enhance their career, or find a shidduch. Intrinsic motivators are long-lasting compared with extrinsic factors.

Finally it is important to be goal-oriented. Select two to three goal-oriented habits and decide what to work on first. While it might seem appealing to engage in multiple habits at one time, focusing on one simple habit at a time may lead to greater behavior change (Gardner, Lally & Wardle 2012). For example, if you want to lose weight, these are all good things to do:

1. Walk and track 10,000 steps per day. There is evidence that regular, “incidental” physical activity is effective for weight loss and overall health.

2. Drink 2 cups of water before every meal. Not only can this help with satiety, but water is calorie-free, and proper hydration may aid in fat loss and contribute to overall well-being.

3. Get to bed earlier (pick a specific time) every night. A good night’s sleep supports the body’s ability to lose weight.

Pick one and work on it, then the next and then the next.

Seeing a dietician or personal trainer will certainly help you with your eating and exercise. It will give you great knowledge toward being healthy. But creating new behaviors based on that information is the key to long term success with any habit you want to change, and it will “add hours to your day, days to your year and years to your life.”

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.