Yeshiva University Museum’s exhibition 500 Years of Treasures from Oxford includes an extraordinary array of manuscripts and printed books seen in America for the first time. These selections from the Corpus Christi College’s Special Collections, normally kept in a vault and rarely accessible except to researchers, chronicle Corpus Christi College’s pioneering role in the study of scripture, humanities and sciences over the course of five centuries.

The manuscripts and books date back as far as one thousand years. The Hebrew works contained within these “treasures” have been called the most important collection of Anglo-Jewish manuscripts in the world.

The manuscripts and books date back as far as one thousand years. The Hebrew works contained within these “treasures” have been called the most important collection of Anglo-Jewish manuscripts in the world.The collection of Hebrew manuscripts includes several volumes of books from the Tanach written in both Latin and Hebrew, designed for use by Christian scholars who wanted to study the Bible in its original language. These collaborations between Jewish and Christian scribes were created during the beginning of the 13th century, before the expulsion of Jews from England. Three centuries later, with the opening of Corpus Christi College in 1517, these volumes became the core library for students studying the three important Biblical languages: Latin, Greek, and the “third language”, Hebrew.

The collection also includes remarkable Hebrew manuscripts originally in use by Jewish communities in Europe, such as a nearly complete Rashi commentary on the Tanach. Rashi and Rambam are the best known Jewish scholars of the Middle Ages, if not of history. Due to the wondrous discovery of the Cairo Geniza, we are blessed to know of – and some of us to have seen – manuscripts written by Rambam’s own hand.

Not so with Rashi, as there are no known extant manuscripts that were personally written by him. We have to rely on copies, both handwritten and later printed, created by a chain of Jewish scribes, scholars, and printers over the past 900 years since Rashi’s death in 1106. Due to the frequency and methods with which Rashi’s work was copied, there developed many different versions of his commentaries, containing many possible “errors” of transmission. If one were to look for the most authentic version of his work, one must search back as close to Rashi’s lifetime as possible.

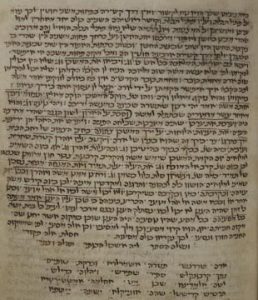

Manuscript 165 in the Corpus Christi collection is such a work. It is a nearly complete copy of Rashi’s commentary on the Tanach, likely produced in the country where Rashi himself lived (France), during the late 12th century. This would make this book the oldest extant Rashi manuscript, and hence, likely one of the most accurate. Furthermore, for those who associate Rashi the scholar with “Rashi script”, the font chosen by 16th century Hebrew printers to distinguish Rashi’s words from the Torah or Talmud text on the page, the Corpus Christi manuscript provides additional insight. If it was indeed written shortly after Rashi’s death, in the same part of the world where Rashi lived and taught so many students, perhaps one can imagine that Rashi’s own handwriting bore some resemblance to that which is visible in MS 165.

Manuscript 165 in the Corpus Christi collection is such a work. It is a nearly complete copy of Rashi’s commentary on the Tanach, likely produced in the country where Rashi himself lived (France), during the late 12th century. This would make this book the oldest extant Rashi manuscript, and hence, likely one of the most accurate. Furthermore, for those who associate Rashi the scholar with “Rashi script”, the font chosen by 16th century Hebrew printers to distinguish Rashi’s words from the Torah or Talmud text on the page, the Corpus Christi manuscript provides additional insight. If it was indeed written shortly after Rashi’s death, in the same part of the world where Rashi lived and taught so many students, perhaps one can imagine that Rashi’s own handwriting bore some resemblance to that which is visible in MS 165.Another fascinating Hebrew manuscript in the exhibition is a 12th century siddur (whose fully digitized contents can be viewed in the gallery) that belonged to a Jew in England. With prayers written in Ashkenazic script according to French custom, the siddur also contains the text of the Passover haggadah. Scholars studying this text have noted the differences in some of the prayers from versions recited today, notably the extended “Shfoch Chamatecha”. The hidden prize in this siddur, however, is the list of personal notes of the owner, contained within the fly leaves. The notes are written in Judeo-Arabic, and provide the details of money lent to various important Christians, some of whose names are known to scholars. This is the only extant evidence of Judeo-Arabic written in England during this time. It reveals the poignant story of nomadic Jewish life that finds this Sephardic businessman migrating up through the Iberian Peninsula, acquiring a siddur in France, and finding work in England.

In addition to the important collection of Hebrew manuscripts, 500 Years of Treasures from Oxford also presents dazzling illuminated texts, the early origins of English, French, and Italian Renaissance works, as well as early printed scientific books exploring the natural and medical worlds – including contemporary sketches of Galileo’s observations of the moon’s surface and a private letter written by Isaac Newton.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.