Although the mitzva of teshuva (repentance) is of a universal nature, and therefore not limited to any specific time period, the ten days from Rosh Hashanah until Yom Kippur are singled out as “days of repentance.” In what way are these days unique with respect to teshuva?

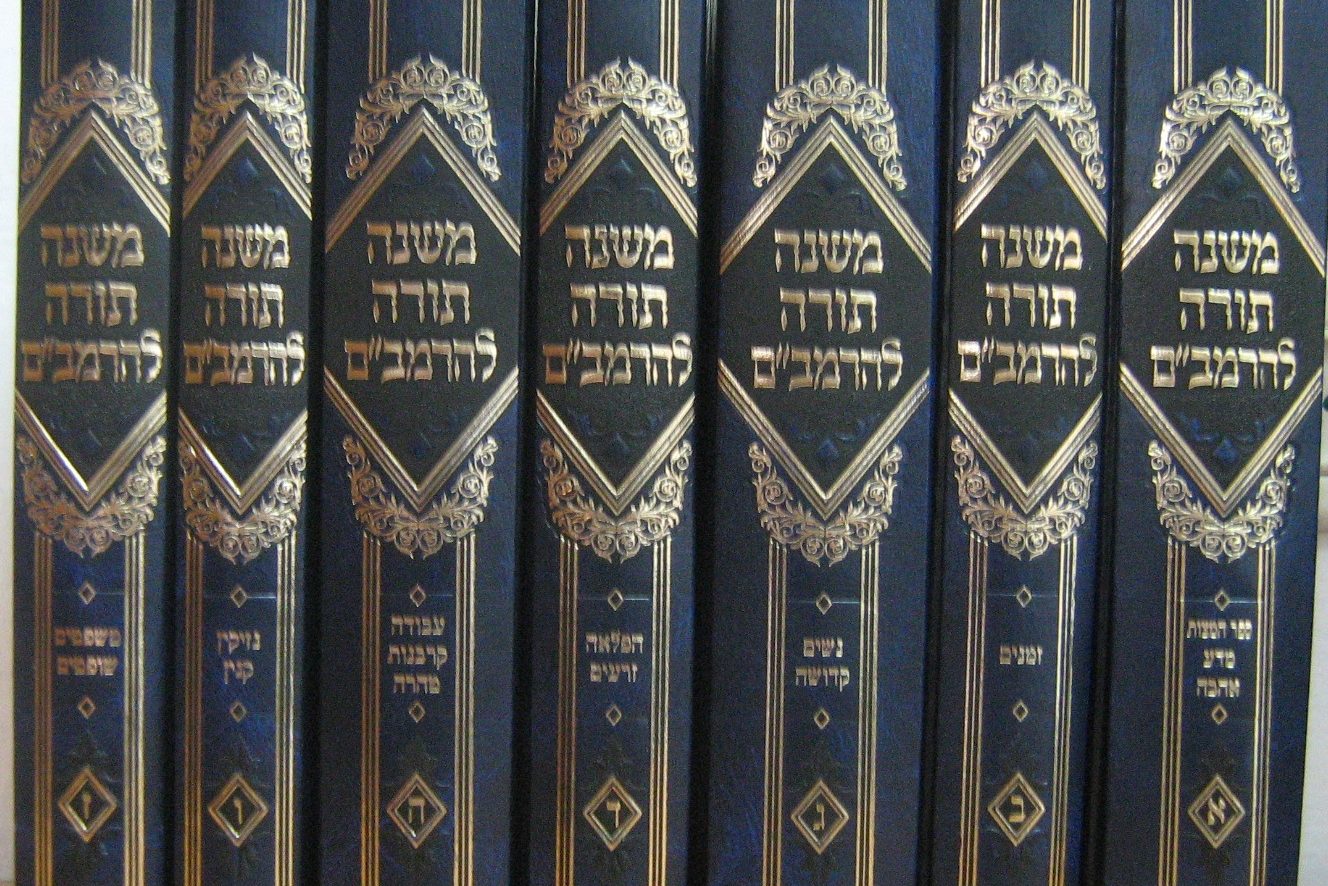

The Rambam in Hilchot Teshuva focuses his discussion on the general mitzva of repentance. Nevertheless, he relates to Asseret Yemei Teshuva in two separate contexts. In chapter 2 (halakha 6), the Rambam writes:

“Although teshuva and pleading are always effective, during the ten days from Rosh Hashana until Yom Kippur they are especially potent and are immediately accepted, as it says, ‘Search for Hashem when He is present.'”

In chapter 3 (halakha 4) the Rambam states: “Although blowing the shofar on Rosh Hashana is a divine decree, it contains a hidden message, namely: ‘Slumberers, awake from your sleep … inspect your actions and repent’… For this reason it is the custom of the House of Israel to increase the amount and level of charity and good deeds and involvement in mitzvot from Rosh Hashana until Yom Kippur, beyond that of the rest of the year. And it is customary to arise at night during these ten days to pray in synagogues … until daybreak.”

These halakhot in the Rambam are perplexing insofar as he separated these two halakhot. Why did the Rambam not simply proceed after stating that teshuva is especially effective during Asseret Yemei Teshuva (Ch. 2), and continue that the shofar contains a hidden message which relates specifically to this time frame (Ch. 3)? After noting the unique quality of these ten days, in which Hashem is present and our teshuva is immediately accepted (Ch. 2), there is an almost natural progression to the custom to increase the amount of good deeds and to recite selichot (Ch. 3). From the order of these halakhot, one gets the clear impression that the Rambam intentionally separated these two accounts of “Asseret Yemei Teshuva.” According to him, the two are unrelated, and refer to independent aspects of the connection between the ten days and repentance.

The answer, I believe, is related to the two independent obligations of teshuva delineated by Rav Soloveitchik zt”l. The first is the requirement to repent from a specific sin. In this case, it is the awareness of sin which generates the obligation of teshuva. This mitzva is described by the Rambam in the heading of Hilkhot Teshuva:

“The laws of teshuva [contain] one positive commandment, that a sinner should return from his iniquity to the presence of Hashem and confess.”

This mitzva is derived from the verse in Bamidbar (5:6-7), “A man or woman who shall commit any sin … they shall then confess the sin which they have committed …”

There is, however, an additional mitzva of teshuva, which applies even in situations where one is unaware of having committed a sin. Despite the absence of awareness, an obligation of teshuva can be generated by suffering. This mitzva is derived from an independent source: “And if you go to war in your land against an enemy who oppresses you, then you shall blow an alarm with your trumpets” (Bamidbar 10:9). This verse is discussed by the Rambam in the heading of Hilkhot Ta’aniyot, where he describe s the mitzva as one of petitioning to Hashem in times of distress and not merely sounding the trumpets: “The laws of fasts [contain] one positive biblical commandment, [namely,] to cry before Hashem in times of great communal distress … and this is a method of teshuva …” Fasting is merely a rabbinic expression of this biblical obligation (see 1:4). Furthermore, the Rambam notes that this relates not only to the community as a whole, but to individuals in times of adversity as well (1:9).

While with regard to the first type of teshuva, the specific sin is acknowledged, with regard to the second it is unknown. Therefore, the teshuva generated by calamity demands not confession but soul-searching. First the offense must be discovered, and only then is repentance possible. (See Rav Soloveitchik’s essay “Kol Dodi Dofek,” footnote 3.)

Let us now take a closer look at the context of the two halakhot we started with. The halakha which relates to the unique quality ensuring immediate acceptance of teshuva during Asseret Yemei Teshuva is found in the second chapter. This chapter begins with a description of complete teshuva, as opposed to teshuva which is wanting. The distinction revolves around the ability of the “ba’al teshuva” to control his desire and overcome his inclination to sin. The entire discussion clearly relates to a person acutely aware of a specific transgression. This individual finds himself in a state of conflict, struggling to conquer his unholy passion which led him to sin. Hence, the second chapter continues the theme of the first, and discusses teshuva which is generated by a specific sin. Within this context, the Rambam introduces Asseret Yemei Teshuva as containing a unique quality which helps to ensure victory in this monumental contest. “Dirshu Hashem be-himatz’o” – seek out Hashem when He is present. During these ten days Hashem is present, as it were, assisting man in his struggle.

In the third chapter, the Rambam abandons the discussion of man confronting a specific transgression, and begins a discourse on the assessment of man’s overall standing. Who is a “tzaddik,” a “rasha,” a “beinoni” (righteous, evil, and middling person)? He then proceeds to apply similar criteria with respect to states, and indeed to the entire world. In the third halakha, the Rambam writes: “Just as man’s deeds and sins are assessed when he dies, so too on every year they are weighed on Rosh Hashanah. Whoever is found to be a ‘tzaddik’ is sealed for life. Whoever is discovered to be a ‘rasha’ is sealed for death. The ‘beinoni’ waits until Yom Kippur. If he repents, he is sealed for life, and if not, he is sealed for death.”

Within this context, the Rambam notes the hidden message of the shofar: “Slumberers, awake from your sleep … inspect your actions and repent …” And at this point, he introduces once again the Asseret Yemei Teshuva: “For this reason it is the custom of the House of Israel to increase the amount and level of charity and good deeds and involvement in mitzvot from Rosh Hashana until Yom Kippur, beyond that of the rest of the year. And it is customary to arise at night during these ten days to pray in synagogues … until daybreak.”

By now it should be clear that the message of the shofar is inapplicable to the second chapter. The shofar is not sounded to aid the sinner in his epic struggle against a specific transgression. Rather, it sounds the alarm to awaken the slumberers who are not even aware of the negative turn that they have taken in life. It comes to warn everyone that the day of judgment has arrived, in which man must account for his actions; his deeds are being weighed and his life assessed. The shofar here plays a similar role to the trumpets sounded in times of crisis, urging man to search his soul and inspect his life. The focus here is not on the first type of teshuva, where man is acutely aware of his sin. Rather, the reference is to the second type of teshuva, in which man is called upon to probe his innermost self. The obligation of teshuva is generated not by an awareness of a specific sin, but by Rosh Hashana as the “Day of Judgment.”

From this perspective, the Asseret Yemei Teshuva are days on which we are called upon to awake and mend the entire direction of our lives. Accordingly, the custom developed to increase the amount and level and good deeds during this period. We wake up at night and recite selichot and petition to Hashem, similar to fast days. And the ten day period is spent in soul-searching, “cheshbon ha-nefesh.”

Thus, we enter Yom Kippur, which is the culmination of Asseret Yemei Teshuva. Optimally, we have fulfilled both obligations connected with teshuva – the one generated by the judgment, as well as that generated by sin. We have been awakened in order to improve the direction of our lives, and we have been afforded the opportunity of overcoming our passions and lusts, which hold us prisoner during the course of the year. May we all be blessed with a “gemar chatima tovah.”