Purim has four main Mitzvot:

- The Reading of the Megillah (Mikra Megillah)

- The Festive Purim Meal (Seudat Purim)

- Sending Gifts (Mishloach Manot)

- Gifts to the poor (Matanot l’Evyonim)

As for prayer adaptations, the Torah portion of ‘and Amalek came’ is read Purim morning, and Al-Hanisim is added to the Shmoneh Esray (Silent Prayer) and Birkat HaMazon (Grace after Meals). Hallel is not, however, said on Purim; the Megillah reading being regarded as the Hallel of the day.

Eulogies and fasting are prohibited on Purim, and in a leap year, they are prohibited in the first Adar as well. A mourner likewise does not practice mourning publicly on Purim. He does not sit on the ground nor remove his shoes, and observes the private aspects of mourning, as is the case on Shabbat.

It is legally permissible to work on Purim, but is nevertheless not considered proper. The Sages have said: ‘Whoever works on the day of Purim does not see any sign of blessing (through his work).’ The type of work that is referred to is work which results in profit. Work involving a Mitzvah, however, or work for the sake of Purim, is fully permitted.

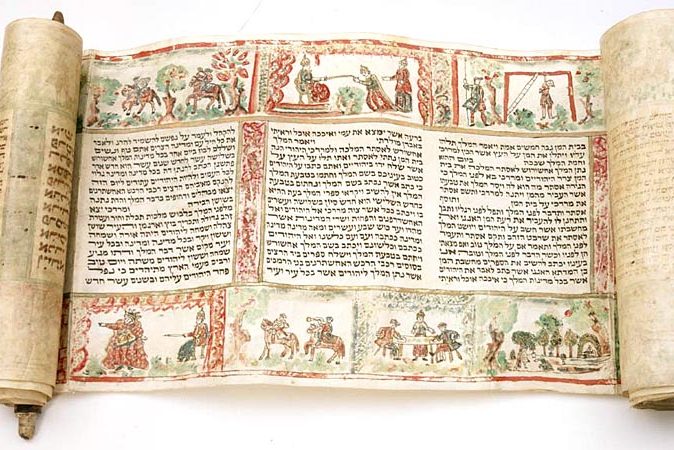

The Reading Of The Megillah

One is required to read the Megillah at night, and then again during the day. The Megillah may be read all night till the coming of dawn. By day, the Megillah may likewise be read from sunrise till sunset. However, if one has read the Megillah even before sunrise, but at least after dawn, he has fulfilled his obligation to read the Megillah. Both men and women are obligated to read the Megillah (or hear it read).

The most preferred manner of fulfilling the Mitzvah is to read the Megillah publicly, and in the Synagogue. Even if there are many people in one’s company, he should not read the Megillah at home, but should rather go to the Synagogue, since, ‘In a multitude there is Majesty;’ and the miracle is made known more widely.

Positive Torah commandments are all deferred for the sake of hearing the Megillah. Even the study of the Torah is suspended for the Megillah Reading. The only Mitzvah which is not deferred by the Reading of the Megillah, is the Mitzvah of providing burial for a dead person, when there is no one else available to do so.

If one hears the Megillah read, he fulfills the obligation as if he were to read it himself; provided that the Reader is himself obligated to perform Mitzvot. It is, however, necessary to hear every single word, for if one has not heard the entire Megillah, he has not fulfilled his obligation.

It is proper for every person to hold a Megillah on parchment before him and to read along in a whisper, as he hears the Reader. If a scroll is not available, then a person should use a printed Megillah.

The Reader pauses when he reaches each of the four ‘verses-of-redemption’ which are found in the Megillah. As he pauses, the congregation reads each verse aloud, and the Reader then repeats it from his Megillah since those who fulfill the obligation of reading the Megillah by hearing it read, are required to hear the entire Megillah read. The following are the four ‘verses-of-redemption:’ ‘There was a Jew in Shushan…’ ‘And Mordechai went forth from before the King in royal garments…’ ‘Unto the Jews there was light…’ ‘For Mordechai, the Jew, was second to the King. . .’ The purpose of this custom is to keep the children from slumber so that the great miracle performed for Israel in the days of Mordechai and Esther, might enter their hearts.

The passage, ‘That night the sleep of the King was disturbed,’ is customarily read aloud; that is, more loudly, and with a variation in the melody, because therein the salvation of the Jews begins to be revealed.

The names of the ten sons of Haman together with the four preceding words [‘500 men and’], and the word ‘ten’ which follows, are all read in one breath: thereby indicating that they were all slain and hung together. The 500 men mentioned with them, consisted of ten groups – each under the command of one of Haman’s sons – who were charged with executing their wishes. If the Reader fails to hold his breath for the duration of the entire passage, he nevertheless fulfills the obligation of the Megillah Reading.

The Brachot of the Megillah

The reader of the Megillah recites three brachot prior to the reading, and one afterwards, and he should intend to fulfill the obligation of the congregation. The congregation answers ‘Amen,’ and they should likewise intend to fulfill the Mitzvah. They do not say ‘Baruch Hu u’varuch Shemo’ – in order not to interrupt in the middle of the brachah. Before the Megillah-Reading three brachot are said:

- ‘Who sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us concerning the Reading of the Megillah…’

- ‘Who made miracles for our fathers in those days at this time…’

- ‘Who kept us alive and sustained us…’

Afterwards, one bracha is said: ‘Who waged our quarrels…’ Two concluding passages follow, as indicated in the ‘Siddur.’ The second of these contains the word: ‘Cursed be Haman and blessed be Mordechai . . . and also Charvonah shall be remembered for good.’ The prayer is an allusion to the Sages’ injunction to utter words of curse against Haman, and of blessing upon Mordechai and Charvonah. The first of the two concluding passages ‘Asher heni’ is not said after the Megillah-Reading by day.

The brachot preceding the Megillah-Reading are said before the reading of the Megillah by day as well; except that in saying ‘Shehecheyanu,’ [‘Who kept us alive’], the Reader should intend to apply his ‘brachah’ to the other Mitzvot of the day – the Purim Feast, the Sending of Gifts, the Giving of Gifts to the Poor.

If one reads the Megillah alone, he recites the ‘brachot’ which precede it, but not the one which follows. If one has already fulfilled the obligation of reading the Megillah, and he wishes to read it a second time publicly for the sake of others, he recites all the ‘brachot’ beginning and end. If one reads the Megillah for another individual, he recites only the first brachot. And if the individual knows the brachot well, he says them himself.

Before the brachah which follows the Megillah Reading, the Megillah is rolled together since it is not respectful to keep the Megillah open after the reading. Before the Reading, the Megillah was folded in the form of a letter, because it is referred to as an ‘Iggeret,’ a letter. When the Megillah is read before women, the first brachah is changed. Since women are obligated only to hear the Megillah read, but not to read it themselves, the word ‘lishmoa’ (to hear) is used, instead of ‘al mikra Megillah’ [‘over the Reading of the Megillah’]. In Sephardic communities, there was an earlier “Pesak” by the Ben Ish Chai, that the Megillah is read for women without a “Berachah.” However, there has been a more recent “Pesak” by Rav Ovadiah Yosef, that the Megillah is read for women with the same “Berachah” – “al Mikra Megillah,” that is recited when the Megillah is read for men. Sephardic communities are divided as to which “Pesak” they follow.

The Festive Purim Meal (Seudat Purim)

It is a Mitzvah to have a sumptuous meal on Purim, including meat and wine.

This meal is held during the day. If one holds it at night, he fails to fulfill his obligation. Nevertheless, after the reading of the Megillah on the night of the 14th [in ‘unwalled cities’], or on the night of the 15th after the Megillah Reading [in ‘walled cities’], one’s meal should be somewhat more festive than usual. One should wear festival clothing and rejoice.

The main Purim meal is held Purim afternoon and is preceded by Minchah. The meal is extended into the night. Most of the meal should, however, be during the day.

When Purim falls on Erev Shabbat, the meal is held early, and is concluded sufficiently before Shabbat for one to be able to partake of the Shabbat meal with a good appetite. Some follow the practice of extending their meal till Shabbat arrives. They then place a Shabbat tablecloth on the table, recite Kiddush, and continue their meal.

The Custom to drink during the Festive meal

The miracle of Purim occurred through wine. Vashti was removed from her throne because of a wine-feast and Esther replaced her. The downfall of Haman was brought about through the wine feasting which Esther held. And through the repentance of the Jews, they expiated their sin in having drunk wine at the feast of Achashverosh

Our Sages of blessed memory, therefore, prescribed the drinking of wine on Purim, and they said: ‘A person is obligated to drink on Purim till he no longer knows the difference between ‘Cursed-is-Haman,’ and ‘Blessed-is-Mordechai.’This does not mean, however, excessive drinking of wine so that one might come to levity thereby; or that he might forget the required brachot or prayer. It is sufficient to drink a little more than is his usual habit, and to take a nap. He thereby fulfills the precept of the Sages: For one who sleeps does not know the difference between a curse and blessing Another explanation of the Purim drinking requirement.

The reason for holding the Purim feast towards evening rather than in the morning, as is the case with other ‘Seudot Mitzvah’, obligatory feasts, Shabbat or Yom Tov, on Shabbat or Yom Tov is that people are busy sending gifts to their friends during the morning hours.

The Gaon of Vilna gave an explanation which is alluded to in the Megillah: The Purim feast is held in memory of the feast held by Esther for Achashverosh and Haman. She held her feast the third day of the fast, two hours before the advent of night. All Israel fasted the full three days and three nights. Esther alone did not fast the entire third day because of the feast. And this matter is alluded to in Esther’s words to Mordechai: ‘And I and my maidens will also fast thus.’ The Hebrew equivalent for ‘thus’ is ‘ken,’ and the numerical value of the two letters which comprise the word ‘ken,’ is seventy. That is to say – ‘I will fast only seventy hours, whereas all Israel are to fast seventy-two hours.’

The Significance of the Purim Feast

The Purim Feast is especially significant in that it elevates the soul as it provides pleasure to the body. It is thus stated in the Zohar that on Purim one may accomplish through bodily pleasure, what he can accomplish on Yom Kippur through bodily affliction.

The people of Israel are invested with bodily holiness as well as with spiritual holiness. And it is proper for their physical actions to be sanctified always, and to be done for the sake of G-d alone. As long, however, as Amalek exists, he corrupts the purity of Israel’s actions. When Amalek’s power is weakened and he is subjugated, the physical actions of Israel are again purified.

Priorities

‘Although it is a Rabbinic precept to eat more fully on Purim, it is preferable for one to extend charity to the poor. For there is no greater joy than to rejoice the hearts of the poor, the orphaned, the widowed, and strangers. And one who rejoices the hearts of these unfortunates is likened to the Divine Presence. As it is said (of God) : (He) ‘enlivens the spirit of the lowly, and restores the heart of the downtrodden’ (Rambam, Hilchot Megillah Chapter 2).

Mishloach Manot (The Sending of Gifts to One Another)

It is obligatory to send a gift which consists of at least two ‘portions’ to another person. Both men and women are included in this Mitzvah.

Only what is edible or drinkable without further cooking or preparation, is considered a ‘portion.’ One may therefore send cooked meats or fish, pastry goods, fruit, sweets, wine and other beverages. And it is the more praiseworthy to send portions to as many friends as possible. Even better, however, is to give more gifts to the poor than to friends.

One of the most popular food items that has been used for this Mitzvah isthe Hamentash, a calorific (fattening) concoction consisting of dough shaped into the form of a triangle [with just two possibilities allowed – exactly sixty degrees in each angle or an isosceles right triangle – just kidding!], with filling of various kinds.

Even a poor person is required to fulfill the Mitzvah of ‘Mishloach Manot.’ If one is unable to do so directly, he may exchange his own food for that of his friend; both of whom would thus fulfill their obligations.

The Mitzvah of Mishloach Manot may not be fulfilled with money, clothing and the like, but only with foods or beverages.

It is proper to send portions sufficient to convey regard for the recipient. One should not send an item so minute as to be worthless in the eyes of the poor.

If at all possible, these ‘portions’ should be sent by messengers, rather than to be delivered personally. And though it is said of all other mitzvot: ‘It is more of a Mitzvah if done personally, than if done through a messenger,’ this Mitzvah is different. Since the term, ‘Mishloach Manot’ (the sending of portions), is the term used in the ‘Megillah’ the proper procedure for fulfilling the Mitzvah, is to do so by messenger. Nevertheless, if one delivers his Mishloach Manot personally, he still fulfills his obligation.

The Mitzvah of Mishloach Manot should be performed by day.

A mourner is free of the obligation, but some hold that it rests even upon him, except that one in mourning should not send gifts which would be a source of rejoicing.

The Mitzvah of Mishloach Manot and the giving of gifts to the poor, during the days of Purim, are prescribed in order to recall the brotherly love which Mordechai and Esther awoke among all Jews. When there is inner unity among Jews, even the wrongdoers among them become righteous.

Gifts to the Poor (Matanot l’Evyonim)

“Acharon, Acharon Chaviv!”

The Last mentioned is the most beloved!

In the Megillah (9:22), where the Mitzvot of Purim are listed, this one is listed last. However, as mentioned above in connection with the “Seudah,” the Festive Meal, of Purim, providing monetary support for the poor is probably the most important of all the Mitzvot of Purim. Yet it tends to be minimized. Proper observance of Purim would require the spending of at least as much on this Mitzvah of Purim as on any of its other Mitzvot.

There is a prophetic precept to give at least two gifts to two poor people on Purim; that is, one gift to each. And even a poor person who himself has to ask for Charity, is required to do so. This obligation is fulfilled through any type of gift; whether of money, of food or drink, or even of clothing. One should, however, try to give a substantial gift. For if one gives a gift of money it should be sufficient for the recipient to buy bread weighing at least three eggs. At the very least, however, one must give a pruta or its equivalent value to each of two poor persons.

These gifts should be given by day. It is proper to give the gifts to the poor after the Reading-of-the-Megillah. If one sets aside a tithe, ten percent, from his income for Charity, these gifts should not be included in that amount. If, however, he gives some slight sum from his own funds and wants to add his tithe, he may do so.

If one has set aside money for gifts to the poor on Purim, he may not change their intended purpose and give them to another Charity.

A person cannot free himself, through his gifts to the poor on Purim, from the general obligation of ‘Tzedakah’ (Charity) which the Torah places upon him. And even a poor person is obligated to fulfill the Mitzvah at least once a year, aside from what he gives to the poor on Purim.

The gifts should be given in sufficient time for the poor to utilize them during Purim – and for their Purim meals. The poor person may do as he wishes with the gifts, however.

The special gifts for the poor which one is required to give for Purim, should not be given earlier, lest the poor partake of them before Purim; in which case the giver will not have fulfilled his obligation (though in any event the general Mitzvah of Tzedakah would apply before Purim.)

One is not strict with the poor on Purim in determining whether they are needy or not. Whoever puts out his hand is to be given a gift. If one fails to find poor persons in his place, he sets the intended gifts aside till he encounters poor people. Women are also obligated to give gifts to the poor on Purim.