“And a New king Arose Over Egypt,

Who Did Not Know Yosef” (Shemot 1,8)

It is difficult to imagine any king in Egypt who reigned at that time not being aware of Yosef’s great accomplishments. After all, it was Yosef whose handling of the Crisis of the Famine had saved the country and preserved, and even strengthened, it would have seemed, the monarchy. After all, the Chumash says in Parshat Vayigash “And Yosef acquired all the land of Egypt for the Pharaoh, because each person had sold their field because the famine gripped them so tightly; And the whole land became the property of the Pharaoh.” (Bereshit 47,20)

It is difficult to imagine any king in Egypt who reigned at that time not being aware of Yosef’s great accomplishments. After all, it was Yosef whose handling of the Crisis of the Famine had saved the country and preserved, and even strengthened, it would have seemed, the monarchy. After all, the Chumash says in Parshat Vayigash “And Yosef acquired all the land of Egypt for the Pharaoh, because each person had sold their field because the famine gripped them so tightly; And the whole land became the property of the Pharaoh.” (Bereshit 47,20)

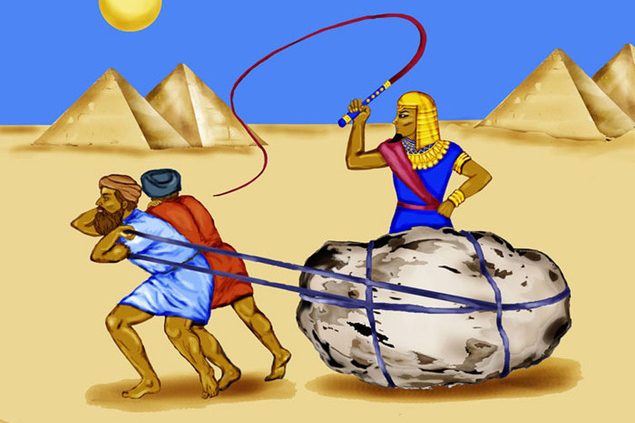

On the other hand, it is easy to see those very actions of Yosef which had so strengthened the Pharaoh, as generating a great deal of negative reaction among the Egyptian People, because all the activity described in the Chumash: the money transfer and the property transfer, the people transfer and the land transfer, which had reduced the entire Egyptian population to indentured servants to the Pharaoh, had taken place while the Jews, the family of Yosef, were thriving in Goshen. “And Yisrael dwelt in the Land of Egypt, in the Province of Goshen; And they took strong hold of it, and they increased and multiplied greatly.” (Ber. 47,27)

It is, I believe, a reasonable possibility that the “not knowing” of Yosef mentioned early in Shemot refers to a revolution against the policies of Yosef, not merely a theoretical clash of ideas, but a true revolution against measures which had reduced the population to a form of slavery, though they themselves had, albeit out of desperation, requested it; “And let us be slaves to the Pharaoh.” (Ber. 47,25).

The “King” referred to was originally a leader of the revolution, who undid the economic policies of Yosef, and sought to repay the debt of slavery to the family of the one who had arbitrarily, without ample justification, so they said, imposed slavery upon them. How quickly the transition from “Behold the nation of the Children of Israel; they have become greater and mightier than us; let us outsmart them…” (Shemot 1, 9-10) to “And Egypt imposed harsh labor upon the Children of Israel.” (Shemot 1, 13)

For the tiny grain of truth in their argument, perhaps, we are cautioned not to recite the whole Hallel on the last two days of Pesach, which commemorate the Miracle of the Splitting of the Red Sea. This miracle saved the Jewish People, but destroyed the Egyptian army. We are to empathize, and understand the application to the Egyptians of the words which the Midrash puts in the “Mouth,” so to speak, of G-d, “My creatures are drowning in the sea, and you want to praise me with song?” And we are also instructed to remember with a degree of gratitude, the initial welcome our father Yaakov, and his family, received from the Pharaoh, when “you were a stranger in his land,” despite the extremely harsh treatment we received at the end.

Thus, Yosef the “Righteous,” was a pivotal, and paradoxical hero of the Jewish People. Never understood, not by his brothers, and not by the Egyptians whom circumstances forced him to treat harshly, he was, in a sense, G-d’s instrument in bringing the Jewish People to Mitzrayim, and in their enslavement.

By his actions, he saved his family from the famine, but, as we have seen, those actions also may have, to a degree, caused their enslavement, thus representing his acceptance, for a time, of Yehudah’s suggestion for expiation of the crime of the brothers towards himself, “And therefore let us be slaves to my master. (Ber. 44,16)”

But he was able, perhaps, also to reduce the term of enslavement which G-d had foretold to Avraham. For G-d had said to Avraham, “Know with certainty that your offspring shall be aliens in a land not their own – and they will serve them, and they will oppress them – for four hundred years.” (Ber. 15,13) But in fact, we know that their period of enslavement was only two hundred ten years! RASHI asks and answers this question by changing the starting point to the birth of Yitzchak.

Perhaps another answer can be given: Yosef has the extremely complimentary adjective “HaTzaddik,” “The Righteous,” appended to his name, because of the super-human degree of self-control he exercised during his attempted seduction by the wife of Potiphar. The “gematria,” or the sum of the numerical equivalents of the Hebrew letters making up the word, “HaTzaddik,” is two hundred nine, which, when supplemented by the number one for the word itself, equals two hundred ten! The merit of his self-restraint was so great that he was able to reduce the period of enslavement of his People in the future, who, the Midrash says, would have “gone under” had they not been redeemed at that point, by one hundred ninety years.

But he also held the key to their permanent redemption, for he said to his brothers on his deathbed, “I am dying, but the l-rd ‘pakod yifkod etchem,’ ‘will surely remember you,’ and raise you out of this land, to the Land which He swore to Avraham, Yitzchak and Yaakov. (Ber. 50,24)” So that Moshe, when he went to the Liberation of Israel, used Yosef’s code word, “And he made the people believe, and they understood, ‘ki pakad Hashem’ et bnei Yisrael, ‘that G-d had remembered’ the Children of Israel, and that He had seen their anguish, and they prostrated themselves and they bowed. (Shemot 4,31)”

And, when the time came to actually leave the House of Bondage, Moshe occupies himself with retrieving Yosef’s remains, while the rest of the Jewish People are busy fulfilling G-d’s indication to Avraham “and afterwards they will leave with great wealth.” (Ber. 15,14) He understood that he was not the only human being who had acted as G-d’s messenger in achieving the Redemption of Israel. So that the Two Liberators could march out together, leading the Jewish People, “beyad ramah,” “with an outstretched arm.”