A Meditation on Sin and Repentance

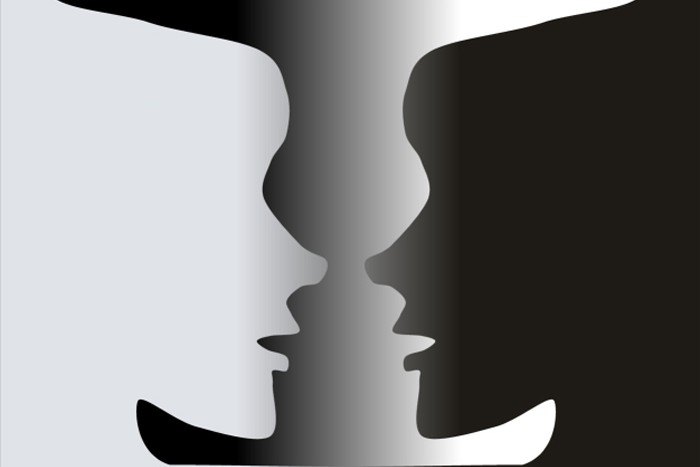

At the core of man is duality. Some might suggest contradiction. Regardless of how it is characterized, man’s essential duality creates tension in his life. For man is both corporal, like every other being that walks the face of the earth, and he is spiritual, imbued with the dignity and divinity of his Creator. At every instance of his life, man teeters and totters, seeking balance between the dual facets of his nature. At each step, he seeks to imbue the natural with the spiritual, lending grace to the most basic of tasks, and to lend humanity to the divine, bringing holiness within his grasp.

At the core of man is duality. Some might suggest contradiction. Regardless of how it is characterized, man’s essential duality creates tension in his life. For man is both corporal, like every other being that walks the face of the earth, and he is spiritual, imbued with the dignity and divinity of his Creator. At every instance of his life, man teeters and totters, seeking balance between the dual facets of his nature. At each step, he seeks to imbue the natural with the spiritual, lending grace to the most basic of tasks, and to lend humanity to the divine, bringing holiness within his grasp.

No moment is more rife with the tension of man’s duality than his confession on Yom Kippur. The process of repentance and its accompanying recitation of the confession – Viddui – highlights the contradiction of man’s nature. On the one hand, Viddui is a singular manifestation of courage, creativity and spiritual and psychological strength. On the other, it is a powerful statement of self-defeat, a pathetic recognition of human frailty, inferiority and unworthiness.

Sincere and authentic repentance depends upon the strength, ability and insight to accuse oneself not only of doing wrong but of possessing a nature that makes such failure inevitable. Viddui is an acknowledgment that one’s intentions and deeds are unworthy and tarnished, a shameful cry that “I have sinned.”

Repentance is a merciless and boundless expression of self-accusation. However, the irony – and some might suggest, the beauty – of this admission of necessary failure is wholly dependent on man’s unique superiority and spiritual greatness. Without such inherent holiness, self-accusation would be impossible. It is only when one is cognizant of freedom, that he can recognize guilt, fragility and temptation and then – and only then – contemplate genuine repentance.

The Viddui experience is meaningless without both aspects of man’s duality. His praise and shame are equal parts of the Viddui experience. Regret requires recognition. Yet, recognition is futile unless man simultaneously has faith in his own sacrality; in his creative abilities and talents, which ultimately allow him to repent, to change and to be renewed and reinvigorated.

Call it a fundamental irony, a fundamental contradiction or a duality, but the praise of man is one and the same as the enabler of his confession. One without the other has no meaning.

Rav Soloveitchik Z”L1 derived these two inseparable elements of the repentance experience from the Viddui recitation of the Jew who apportions his Ma’asrot during the fourth and seventh years of the Shemittah cycle. Such a Jew boasts that he has not violated not even one iota of the commandments; he has fulfilled the Mitzvah of Ma’assrot to the letter.

“According to all your Commandments which You have commanded me: I have not transgressed any of Your commandments, neither have I forgotten. I have harkened to the voice of the Lord my God, I have done according to all that You have commanded me.”

Such statement in praise of a man extolling his virtues as a God-fearing and obedient servant is categorized by the Sages as a “confession?!” How is it possible to ascribe “confession,” a word which conjures up images of weakness and helplessness, to a man elevated to the point of not having “transgressed any of Your commandments?” the Rav Z”L asked. But, that is precisely the point. Only a person proud enough to announce that he has done “all that You have commanded,” is also to be expected to humbly submit and admit that he has “not done according to all that You have commanded.

The one who possesses the insight and strength to do right is also expected to acknowledge that which is not right. The ability to recognize success is a prerequisite to admission of failure. Both emanate from the same source; both lead to mutually exclusive conclusions – the nullity of being and the greatness of being.

The nullity of being leads to the Yom Kippur confession. The greatness of being leads to the Ma’assrot confession. Both are rooted in humans, created from earth’s dust in the image of God.

Both forms of confession can at times be integrated. The greatness of being can indeed overshadow the nullity of being.

When the Klausenberg Rebbe Z”L addressed survivors from Hungary, Rumania, and Czechoslovakia in the Feldafing DP Camp on Kol Nidre night in 1945, the greatness of being overpowered the nullity of being, despite the dire circumstances and the historical context, which might have led a “rational” thinker to focus on the nullity of existence. Lieutenant Birnbaum2 reported that he “had never heard so powerful a speech and never will again. When he finished, more than two hours later, I was both emotionally drained and inspired for the best davening of my life.”

What did this great Rebbe who himself had lost his wife and eleven children to the Nazis say to those who could still see and smell the stench of the crematoria? How could he speak of confessions to those who had witnessed such depraved acts? How could he speak of such things in the presence of millions of fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, husbands, wives and children?

The Rebbe stood with his Machzor in hand, calmly flipping through its pages. Periodically he would ask rhetorically, “Wher haht das geshriben – who wrote this? Does this apply to us? Are we guilty of the sins enumerated here?”

One by one, he went through each of the sins listed in the Ashamnu (we have become guilty) prayer and then the Al Chait and concluded that those sins had little to do with those who survived the camps. He analyzed each of the possible transgressions one by one:

Ashamnu. “Have we sinned against Hashem or man? I don’t think so.”

Dibarnu dofi. “We spoke no slander. We didn’t speak at all. If we had any strength to speak, we saved it for the SS guards so that we could avoid punishment.”

Latznu. “But we were so serious in the camps. There was no scoffing; no such thing as smiling or making a joke.”

Moradnu. “Rebelled? Against whom should we have rebelled? Hashem? We weren’t able to rebel at all. If we had tried to rebel against the Nazis it would have been our last rebellion.”

And so, the Klausenberger concluded with the Ashamnu prayer and turned his attention to the more detailed Al Chait. Once again, he concluded with the pride of one whose greatness of being supersedes the nullity of being; that the recitation of sins enumerated in Al Chait hardly applied to the worshipers in Feldafig Block 5A.

Al Chait she’chatanu lifanecha b’ones uvreratzon – for the sins that we have sinned before You under duress and willingly – “We certainly did not observe the mitzvot in the camps because we were forced to.”

Bevili daas – for the sins that we have sinned without knowledge – “Our minds were in such a state that we did not have knowledge of anything.”

B’tipushus peh – for the sins that we have sinned with foolish speech – “That’s a gelechter (funny). Who spoke foolishly or lightheartedly in the situation we were in?”

B’Yetzher hara – for the sin that we have sinned with the evil urge – “To sin with the yetzer hara you must first have possessions of your physical sense of touch. We were skin and bones, incapable of touching. The only thing we could feel were the corpses we carried out every morning. We heard only one thing, the commands of our guards. We had ears for nothing else. Our eyes were only looking around to see whether our guards were watching when we wanted to take a rest. Otherwise we were as blind men seeing nothing. Smell – yes, we had a sense of smell. The unforgettable stench of death was constantly in our nostrils making us nauseous. Taste – the only taste we knew was the thin soup they gave us so we could have enough strength for another day’s work. On these, I forget, we did have the yetzer hara for food, for the slop that we saw thrown to the pigs. What the SS officers would not eat they threw to the pigs. How we envied the pigs.”

And so the Rebbe Z”L eliminated the Al Chaits one by one, emphasizing how all of these transgressions did not apply to his congregation.

In conclusion, he brought the cover of the Machzor to a close.

Seeing the Rebbe close the Machzor, Lieutenant Birnbaum was certain the Rebbe was finished. But then the Rebbe asked once again his original question, “Who wrote this Machzor? I don’t see anywhere the sins that apply to us, the sins of losing emunah and bitachon (faith and trust in G-d)!

“Where is the proof that we have sinned in this fashion? How many times did we recite Krias Shema on our wood slats at night and think to ourselves: Ribbono shel Olam, please take my neshama, so that I do not have to repeat once again in the morning. ‘I’m thankful before You who has returned my soul to me.’ I do not need my soul. You can keep it. How many of us went to sleep thinking that we couldn’t exist another day, with all bitachon lost? And yet when the dawn broke in the morning, we once again said Modeh Ani and thanked Hashem for having returned our souls.”

“None of us expected to survive. Every morning, we saw this one didn’t move and that one didn’t move, and as we carried the dead out we looked upon them with envy. Is that emunah in Hashem? Is that bitachon in Hashem?

“So, yes, we have sinned. We have sinned and now we must klop al Chait. We must pray to get back the emunah and bitachon that lay dormant these years in the camps. Now that we are free, Ribbono shel Olam, we beg You to forgive us. Forgive everyone here. Forgive every Jew in the world.”

Rav Soloveitchik Z”L taught that every confession expresses itself in the outcry: “I am black, and I am beautiful, Oh daughter of Jerusalem.” For, when we fail to see the “beauty” we cannot hope to discern the “blackness.”

Genuine repentance demands that the sinner view himself from the seemingly two antithetical viewpoints, the two fundamental truths of his being – from the nullity of being and the greatness of being.

The Klausenberger Rebbe Z”L clearly saw both.

May He grant us the strength, courage, humility and wisdom to see both as well.

Shanah Tovah.

Footnotes

1. In Shiurei Harav edited by Joseph Epstein, Ktav Publishing, 1994

2. Lieutenant Birnbaum-A soldier’s story by Meyer Birnbaum with Yonasan Rosenblum, Mesorah Publications, 1994

Rabbi Dr. Eliyahu Safran serves as OU Kosher’s Vice President – Communications & Marketing. His book: Meditations at Sixty- One Person, Under God, Indivisible KTAV 2008, was published last summer.