And when Haman saw that Mordechai bowed not down, nor prostrated himself before him, then Haman was full of wrath. But it seemed contemptible in his eyes to lay hands on Mordechai alone; for they had made known to him the people of Mordechai. And Haman sought to destroy all the Jews that were throughout the whole kingdom of Achashverosh, even the people of Mordechai. (Megilat Esther 3:5-6)

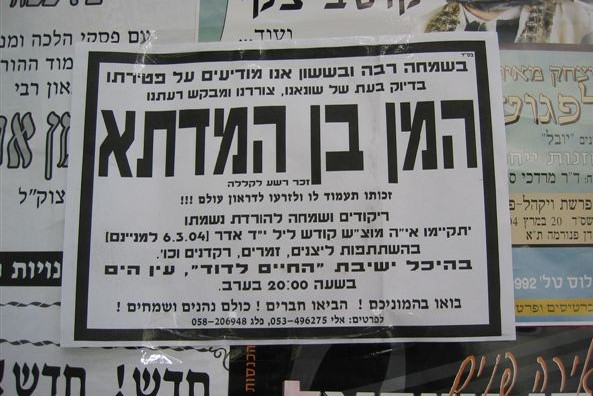

- The confrontation between Haman and Mordechai

Megilat Esther focuses on two aspects of Haman’s character. It explains the strategy he employed in order to manipulate Achashverosh. The Megilah also explores the nature of Haman’s wickedness. It delves into the source of his pathological fixation upon Mordechai and the Jewish people. However, the Megilah’s treatment of this issue is not manifestly expressed in its passages. Instead, careful consideration of two incidents is required for the Megilah’s message to emerge.

Haman seems to acquire his hatred for the Jewish people soon after his appointment as Achashverosh’s vizier. The Megilah explains that with this appointment came a directive that all members of the court and subjects of the king pay homage to Haman by kneeling and prostrating themselves before him. This directive was obeyed by the king’s servants and subjects. Mordechai, alone, refused to obey the royal directive and pay homage to the king’s vizier.

Apparently, Mordechai’s behavior did not immediately disturb Haman. It seems that initially he was not even aware of Mordechai’s refusal to follow the king’s edict. However, among those who observed Mordechai’s behavior, his refusal to kneel and prostrate himself before Haman was sensational. These observers understood from Mordechai that his actions expressed his convictions as a Jew. They made Haman aware of Mordechai’s behavior. They wanted to precipitate a conflict between Haman and Mordechai and see who would triumph. The Megilah explains that at this point Haman first took notice of Mordechai and discovered that the report brought to him was accurate. Indeed, Mordechai would not kneel or prostrate himself before him.

Haman was consumed with anger. His anger was provoked by Mordechai but it extended to all Jews. Haman decided that he would seek the destruction of all Jews in the kingdom.

Two aspects of Haman’s reaction to Mordechai require further consideration. First, the Megilah explains that when Haman became aware of Mordechai’s resistance he was filled with anger. Haman enjoyed virtually universal recognition. One single individual – Mordechai – refused to efface himself. Mordechai’s lonely protest was so insignificant that Haman did not even notice it until instigators brought it to his attention. Why was Haman so infuriated by Mordechai’s actions? Second, the Megilah describes Mordechai as an outlier even among Jews. Apparently, other Jews obeyed the king’s directive. Why did Haman decide to destroy all of the Jews because of Mordechai’s behavior?

And Haman recounted unto them the glory of his riches, and the multitude of his children, and everything as to how the king had promoted him, and how he had advanced him above the princes and servants of the king. Haman said moreover: Yea, Esther the queen did let any man come in with the king to the banquet that she had prepared but myself; and tomorrow also am I invited by her together with the king. Yet, all this avails me nothing, so long as I see Mordechai the Jew sitting at the king’s gate. (Megilat Esther 5:11-13)

- Mordechai’s profound effect on Haman

In order to answer these questions, another incident should be considered. As the story of the Megilah progresses, Haman persuades Achashverosh to allow him to issue a decree promoting the annihilation of the kingdom’s Jews. Mordechai appeals to Esther the queen to intercede with Achashverosh and ask that he revoke the decree. Esther decides against directly appealing to Achashverosh. Instead, she invites the king and Haman to a party she has prepared exclusively for them. This party does not provide Esther with an opportunity to appeal to Achashverosh. Esther invites Haman and Achashverosh to second exclusive party the following night.

Upon leaving the queen’s residence, Haman encounters Mordechai. Again, Haman’s nemesis refuses to pay him homage. Haman in enraged. He returns to his home and gathers his closest confidants and his wife. He delivers an address. He begins by describing his fame and wealth. He boasts of his many sons. He proudly notes that even the queen acknowledges his singular position in the kingdom. She has twice included him alone in intimate parties she has made for the king. Then, Haman makes an amazing statement. He declares that all his accomplishments, his wealth, and his glory are rendered meaningless by Mordechai’s defiance.

How can this be explained? Why did Mordechai’s behavior have such a powerful effect on Haman? How is it possible that all of Haman’s accomplishments were rendered meaningless by the defiance of this one lonely Jew?

The answer to all of these questions is provided by a comment of our Sages. The Sages are discussing Mordechai’s reason for not obeying the king’s directive to pay homage to Haman. They explain that Mordechai refused to obey the directive because Haman had made himself into a deity.[1]

The actual narrative of the Megilah does not seem to support the conclusion that Haman ascribed supernatural powers or omnipotence to himself. The Sages are not necessarily suggesting that the Megilah omitted this important element of the narrative. Instead, perhaps the Sages are suggesting that Haman was enamored with his perception of his own greatness. He believed himself to be singular, powerful, and brilliant. He perceived himself as the master of fate and destiny and as the potentate who either ruled or manipulated all others. He deserved the acknowledgement of lesser human beings and their adulation.[2]

Of course, this outlook is an absurd presumption for any human being. We are all frail creatures. We cannot control nature or protect ourselves from its extremes. A single sick cell within our complex bodies can multiply unchecked and bring us to an untimely end. Our power and our influence over our destiny are illusionary. At times we may entertain an illusion of greatness, but a sudden change in our finances, the illness of a friend or family member brings reality home to us.

Because the discordance between reality and Haman’s fantasy was so extreme he was required to resort to extreme measures to maintain his illusion. His energy was devoted to supporting his fantasy and suppressing any evidence that contradicted his illusion of greatness. We can imagine Haman’s thinking. If others experienced sudden financial ruin, it was because they were not as wise as he. If others were confronted by children or wives who rebelled against their authority, it was because they did not wield their authority as effectively as he. If others were struck by illness or even death, it was because they lacked his physical vigor.

Now, Haman’s reaction to Mordechai has a context and is understandable.

Mordechai was a lone, humble, exiled Jew. He was not a notable significant personage. In fact, before it was brought to his attention, Haman had no reason to monitor or even notice Mordechai’s behavior. However, once brought to his attention, Mordechai’s insignificance made his resistance an even greater affront and threat to Haman. That a simple, powerless, single, exiled Jew could resist his power and authority, was a complete contradiction to Haman’s illusion of greatness. It was impossible for Haman to reconcile Mordechai’s brave resistance with his all-consuming fantasy of power and grandeur. The Megilah beautifully captures all this in its description of Haman’s conversation with his wife and closest confidants. He enumerates his accomplishments. He presents the impressive evidence of his greatness. Then, he declares that all of this is rendered meaningless and worthless by Mordechai’s resistance. How did Mordechai acquire such powerful sway over Haman? Ironically, Mordechai’s humble status and his insignificance gave him this power. His resistance undermined all of Haman’s efforts to create and maintain his fantasy of human greatness. If this insignificant Jew could not be controlled and subdued, Haman’s claims to greatness would be proven to be nothing more than an illusionary pretense.

However, Haman recognized that Mordechai was the product of a worldview. Although the other Jews of Shushan may not have shared Mordechai’s bravery, Haman realized that the Torah was the source of Mordechai’s worldview and resistance. According to this worldview, no human being is all-powerful. The success of every human endeavor depends on the benevolence of a Creator who is truly omnipotent. Man is actually a weak and fragile creature dependent upon the kindness bestowed upon him by his true heavenly master. This day Mordechai stood alone in his courageous disobedience. However, as long as the people of the Torah existed, new “Mordechais” would emerge. Haman knew that the threat to his fantasy was not only Mordechai. The true danger was presented by the Torah and those who studied and adhered to its lessons. This meant that the Jewish people must be destroyed with Mordechai.

And Haman said unto King Achashverosh: There is a certain people scattered abroad and dispersed among the peoples in all the provinces of your kingdom; and their laws are diverse from those of every people; neither do they keep the king’s laws. Therefore, it profits not the king to suffer them. (Megilat Esther 3:8)

- Haman’s manipulation of Achashverosh

Haman’s fantasy of greatness was not contradicted by his subservience to the king. Haman realized that the king had ultimate authority. However, he was confident in his ability to manipulate Achashverosh to achieve his own ends. His success in convincing Achashverosh to kill his own loyal subjects confirmed to Haman that he was the true power in the kingdom. How was Haman able to so effectively control his king? What was his strategy?

The Megilah provides an indication of his methods in its introduction of Haman. It explains that Haman’s appointment as vizier followed the events described in the prior chapter. The final episode in the prior chapter was the plot by two of the king’s entourage to assassinate him. The Megilah explains that their plot was uncovered by Mordechai, reported to the king, and they were executed. Apparently, this episode led to the appointment of Haman.

The opening passages of the Megilah describe two elaborate celebrations that Achashverosh convened to commemorate his consolidation of control over his kingdom. Our Sages explain that Achashverosh did not inherit his throne. He seized it.[3] The plot against him by members of his own entourage suggested some members of the court continued to oppose him. Haman’s appointment followed Achashverosh’s narrow escape from assassination. This indicates that Achashverosh’s appointment of Haman was at least partially motivated by concern over his personal security and the stability of his control over his kingdom.

Haman recognized Achashverosh’s preoccupation with his personal security and his fear that rebellion might erupt at any moment. He used these fears to manipulate his king. He described the Jews as an ethnically discrete people that held itself apart from the rest of the population. He also noted that the Jews lived throughout the kingdom. Haman understood that Achashverosh would perceive the Jews – described in this way – as a perfect fifth column. Their separateness would suggest to a paranoid Achashverosh that their loyalty should not be assumed. Their dispersion throughout the kingdom would suggest to him that they were potentially the basis for a widespread network of resistance to his authority. Achashverosh would conclude that the Jews posed an ongoing threat to his security. He would eagerly hand them over to Haman for extermination.[4]

In short, Haman was a perceptive interpreter of Achashverosh’s needs, desires, and fears. He understood how to utilize his insight into Achashverosh to pursue his own personal agenda. He combined this understanding with a capacity to package his own objectives in a form that would appeal to his king’s fears and insecurities. Perhaps, these characteristics of Haman are the basis of the contention of the Sages that Haman and Memuchan were a single character.[5]

And Memuchan answered before the king and the princes: Vashti the queen has not done wrong to the king only, but also to all the princes, and to all the peoples, who are in all the provinces of the king Achashverosh. For this deed of the queen will come abroad unto all women, to make their husbands contemptible in their eyes, when it will be said: The king Achashverosh commanded Vashti the queen to be brought in before him, but she came not.

And this day will the princesses of Persia and Media who have heard of the deed of the queen say the like unto all the king’s princes. So will there arise enough contempt and wrath. (Megilat Esther 1:16-18)

- Memuchan is Haman

Memuchan appears earlier in the Megilah than Haman. In this earlier episode, Queen Vashti was summoned by a drunken Achashverosh to display herself before the commoners of Shushan. Our Sages explain that Vashti was the scion of the royal family and refused to be made into a spectacle for the entertainment of the boorish king and his commoner companions. Achashverosh understood Vashti’s response as a rebuke, a reminder of his humble origins, and as an expression of the queen’s pretensions of superiority. He responded with intense anger.[6] Yet, he saw no means by which he could punish the queen. Apparently, he did not feel he could enter into a confrontation with a member of the royal family.

Memuchan provided Achashverosh with a solution. He suggested that Achashverosh recast his conflict with Vashti. He should portray Vashti as a social radical promoting a dangerous attack on conventional family values – as a subversive social revolutionary determined to undermine the authority of husbands in their own homes. Thus recast, the conflict could be addressed. The king would play the role of champion of traditional values. He would be free to act against Vashti and punish her as he pleased.

Memuchan understood his master’s true desires. He recognized that Achashverosh was not interested in his counselors’ advice regarding how to best respond to Vashti’s challenge to his authority. Achashverosh knew how he wanted to respond. He wished to severely punish his queen. Memuchan perceived that Achashverosh was seeking a means by which to exact his vengeance. Also, Memuchan demonstrated a remarkable capacity to package Achashverosh’s destruction of Vashti as a moral imperative. He transformed an act of personal vengeance into a courageous defense of fundamental social values. Both of these traits are identical to the talents demonstrated by Haman. Perhaps, these similarities suggested to the Sages that Haman and Memuchan were a single character.

________________________________________-

[1] Midrash Rabba, Esther 7:8.

[2] See Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, Days of Deliverance, pp. 35-37.

[3] Rabbeinu Shlomo ben Yitzchak (Rashi), Commentary on Megilat Esther 1:1.

[4] Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, Days of Deliverance, pp. 81-85.

[5] Masechet Megilah 12b.

[6] Masechet Megilah 12b.