The Story of Purim

Introduction

Introduction

Purim is known as the Holiday of the “nes nistar,” the “hidden miracle.” This is because HaShem saved the Jewish People without splitting any seas, or making mountains dance and catch fire, as he had done with Mt. Sinai, when he gave His Torah to the Jewish People there some thirty three hundred years ago. In the miracle of Purim, nothing that strange happened.

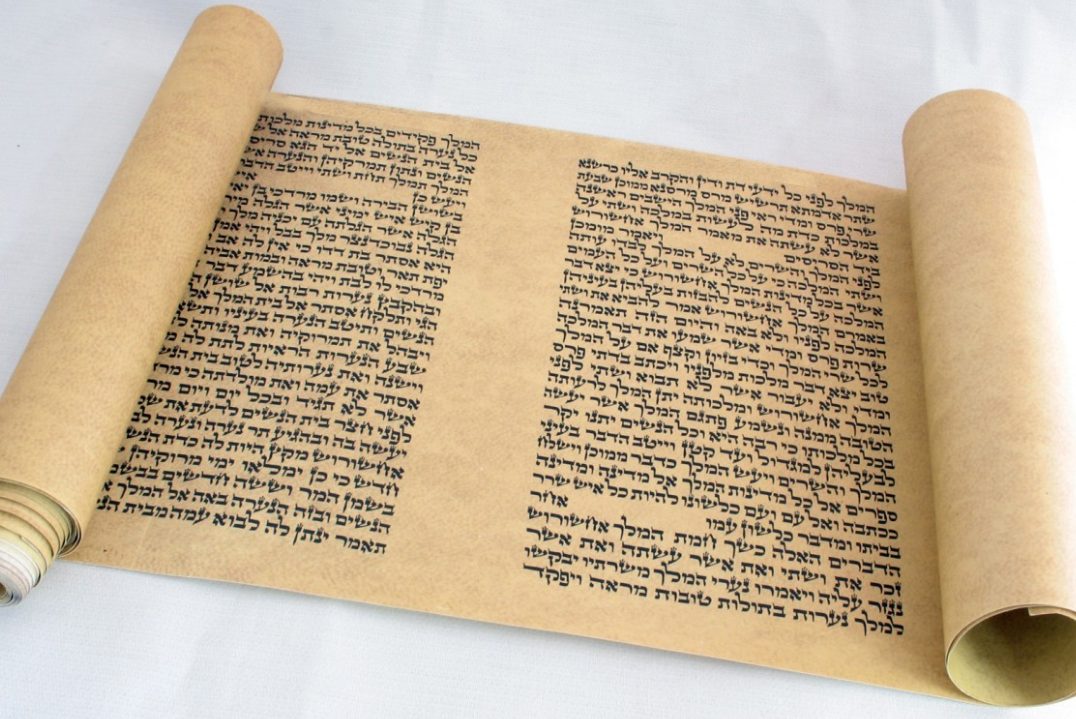

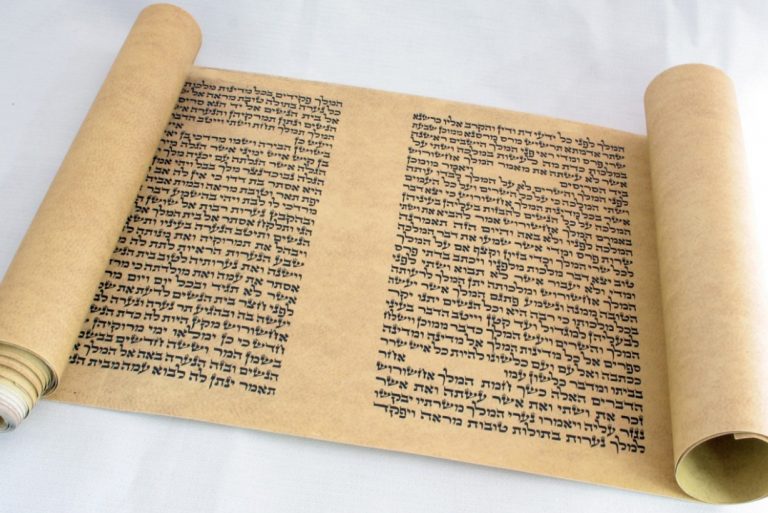

Megillah

It was rather the way that events were tied together – overheard conversations, the pride of a tyrant that “went before his fall,” the sleeplessness of a King, the watchfulness of the King of Kings, that allowed the People to be saved, once they had done “Teshuvah,” Repentance, for a sin only alluded to in Megilat Esther.

Megilat Esther is the story of men and women, some very righteous, some terribly wicked, and how they interacted – with the Holy One, the Producer and Director of the Play, Who miraculously allows freedom of choice, watching from behind the scenes.

The End of the Babylonian Empire

In the Book of Daniel, Chapter 5, we find the scene of the last Babylonian ruler, Belshazzar, the son of Nebuchadnezzar, at the center of a party. The purpose of the great feast is to celebrate the abandonment of the Jewish People by their G-d. For the Prophet Yirmiyahu had prophesied that the Jewish People would be in Exile in Babylonia for seventy years, following which they would be redeemed. Belshazzar had calculated the seventy years, he thought, and no redemption had come for the Jews. Hence he thought it safe to take out the vessels that were taken from the Temple by his father, and they could be used and abused by the party-goers.

Then a hand had appeared and had written upon a wall the enigmatic phrase “Mene Mene, Tekel Upharsin.” Not one of his magicians or advisors had been able to read, let alone decipher those words. But Belshazzar’s wife had reminded him of the presence in the palace of a Jew from the Captivity of Judea, Daniel, who was able to interpret things that were above the comprehension of other men. Daniel was summoned and told him that the words were a message from the L-rd that the time of the Kingdom of Babylonia had ended. And indeed, that night, there was an invasion by the Persians and Medes, and Belshazzar was slain. Persia and Media were the new ruling nations of the World, and Darius the Mede was the first King of the new Empire.

The Beginning of the Megilah – Another Feast!

The Megilah begins by informing us that its historical context is the Persia-Media of King Achashverosh, who then ruled over the Empire. That MegillahEmpire encompassed one hundred twenty seven states and provinces (definitely not to be confused with the one hundred twenty seven righteous years of our Mother, Sarah); in effect, the entire (more-or-less) civilized world at that time.

Achashverosh is making a feast for all of his Kingdom, and for the same reason that the unfortunate Belshazzar made one! Again, Achashverosh has done his homework, and is convinced that Yirmiyahu’s seventy years are by now certainly over (wrong again!).

Actually, there are two reasons for Achashverosh’s feast. The most important one is to celebrate the supposed abandonment of the Jewish People by their G-d.

The second reason for the feast has to do with the fact that he wants to keep his population, especially the most powerful members of it, including the army, its officers and all the princes and princesses, dukes and duchesses, etc., happy. For, the Midrash tells us, Achashverosh is not of “royal blood.” Rather, he has come to power through a revolution. Therefore, he is never totally sure of himself in his role as King. His wife, Vashti, the Queen, is however a genuine “blue-blood,” being from the House of Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, and World Conqueror, as she does not hesitate to remind her husband, as we shall see.

Also on the guest list are the Jewish People. Achashverosh goes all out to make them comfortable; he has “glatt kosher” meat, under impeccable “hashgacha,” perhaps under the “OU” of the time. The Jews, on the other hand, have weighed their options. A beautiful catering hall, great food, terrific smorgasbord, and the King’s probably correct in his calculations. They feel a little queasy about celebrating with vessels from the Temple not only on display, but in use. But the majority of them have come.

And it is their presence at a feast celebrating their abandonment and mocking their Temple that, according to the Midrash, has made them guilty of treason against G-d, and therefore candidates for destruction!

“Also Queen Vashti Made a Feast for the Women”

The Tale (Tail(?)) Continues

Not to be outdone, Queen Vashti made a feast for the women of the Kingdom. Her purpose was to show off her great beauty, since she had been one of the most beautiful women in the world. But HaShem spoiled her party. She developed a full-blown case of leprosy. Others say she actually grew a tail!

These blemishes were appropriate punishments for Vashti, for her abuse of her captive Jewish girls. She had made them work for her on Shabbat completely naked, thus greatly offending them from the point of view that they would have to violate the Shabbat, and also by preventing them from practicing the characteristic of “tzniut,” modesty, which was a major part of their life-style. So HaShem punished her “Midah K’neged Midah,” “Measure for Measure,” by not allowing her to make a display of her “pritzut,” her total immodesty.

“Bring Vashti the Queen,…, with (only) the Royal Crown”

Her predicament became worse. On the “seventh day,” the Shabbat, Achashverosh, now totally drunk, demanded that Vashti appear before him and his guests. Of course, in her present state, Vashti refused, not out of a sense of modesty, but out of a sense of embarrassment over her appearance. Not only did Vashti not come – she also sent the King an insult – “Who was he, just a commoner, to tell her royal self what to do?”

This had never happened before! No one, certainly not the queen, had ever been summoned to come before the King, and refused. What a humiliation! One of the King’s advisors, named “Memuchan” in the Megilah, but identified in the Midrash as none other than Haman, suggests that Vashti should be severely punished. Not only has she made a fool of the King before all his royal guests, but soon the story will spread across the Kingdom, that wives don’t have to obey their husbands any longer!

To prevent this scandal from becoming public knowledge, Vashti should be given a taste of the King’s “justice.” Never more should she be allowed to come before the King! And, in those days, that usually meant that poor Vashti would lose her head.

(We see that Haman already has his eye on the throne and is out to remove all obstacles, such as the queen, from his path.)

The King issued a royal proclamation to the effect that there would be no change in the relationship between husbands and wives as a result of the unfortunate and misguided behavior of Queen Vashti. Husbands would continue to “rule in their castles,” be they shoemakers or Kings, and wives would remain in their obedient status, OR ELSE!

The Contest for a New Queen

Enter Esther

It was not long after the unfortunate demise of Queen Vashti that Achashverosh felt lonely for a new queen. Of course his advisors were ready with a solution – to stage a contest – a combination of a “Miss Persia”-style beauty pageant, combined with a search for a girl with true royal qualities.

At this point, the Megilah introduces us to Mordechai, a descendant of Shaul, the first King of Israel, a member of the “Sanhedrin,” the Jewish Supreme Court, and a recent exile from Yerushalayim. He raised the young Esther, who had lost both her parents. Taking note of Esther’s great beauty and fearing that she would be snatched up in the contest of what was originally supposed only to include unmarried women, Mordechai married his young niece.

There was a frantic search throughout the Empire, from India to Ethiopia, for this gem of a girl who possessed both great beauty and royal qualities. Many candidates were quite interested and were brought to Shushan for their one-night tryout with the King. Each was given their choice of clothing, cosmetics, music, entertainment, you-name-it, but the King was still unsatisfied. When the search was enlarged to include married women, they came to Mordechai’s home, and were immediately struck by Esther’s beauty and character.

Mordechai realized that this strange occurrence must be an act of HaShem, to place a Jewess inside the palace, close to the King. He didn’t know yet from what direction the danger would be coming, but he felt confident that HaShem was creating the “refuah,” the healing, before administering the harmful blow. He spoke at great length with Esther about this thought, and she finally consented to go with the King’s men, although her first reaction was to refuse, and be killed.

Esther asked only for the minimum requirements, which were readily supplied her because everyone who saw her was taken by her charm. Achashverosh was delighted with her, and Esther was crowned the new Queen of Persia and Media, and a Feast was proclaimed in her honor.

Bigsan and Seresh, Some Bodyguards!

Life had returned to normal in the palace, but Mordechai was getting more and more anxious about Esther. It happened one day, when Mordechai was in the royal courtyard, which he had access to as one of the heads of the Jewish community, that he heard two voices. The voices were soft, but not soft enough, considering what they were talking about! These were two men of the King’s security staff, in highly trusted positions, plotting the assassination of the King!

They were a province at the far end of the Empire, Tarsis, where they spoke in a language which most people had never heard of, much less understood. That was why they were not nervous about being overheard. But Mordechai was a member of the “Sanhedrin,” each member of which was required to speak seventy languages, including the language of Tarsis. He heard the details of the plot, which involved poisoning the King in just a few days. He quickly requested a private audience with the Queen, Esther, and told her of the plot. The Queen told the King about the plot that night, in the name of Mordechai. The plotters were apprehended, hung from the gallows (trials were considered wasteful of tax-payers’ money in ancient Persia), and the details of the plot and its aftermath were recorded in the Chronicles of the King.

The Rise of Haman

Due to Haman’s usefulness in the matter of Vashti, and his general aggressive and persistent requests for promotion (and generally, making a nuisance of himself), Haman was given the promotion that he had been seeking. Thus, in the short-term, Haman could be considered fortunate; although, in the long-term, his head would be raised in the manner of the Chief Baker of the Pharaoh in Egypt as part of the celebration of the Birthday of the Pharaoh.

He was appointed to the second-most-powerful office in the land, assistant King, which he interpreted as equivalent to god, and everybody was ordered to bow down to him as he rode by in the streets of Shushan, or wherever Haman traveled in the great empire. But there was one dissident, who refused to bow down to Haman. That was Mordechai, who bowed to no one but HaShem.

“Guide for the Perplexed”

Perplexed by the behavior of this one bearded individual, who was steadfast in refusing to bow before him, Haman demanded that palace officials investigate the matter. These officials determined the family background of Mordechai and spoke at length with him, endeavoring to find out why he was disobeying this simple command of the King. But for Mordechai, it wasn’t even a question – in his Religion, Judaism, there was no provision for bowing before anyone or anything but HaShem, the true G-d.

When he received this information, Haman went from “perplexed” to “apoplectic;” for in his family tradition, there was little love for Jews. King Shaul had wiped out almost his entire nation at the command of HaShem, sparing only the King of Amalek, Agag, from whom Haman was a direct descendant. Of course, there had been good reason for that; namely, that his people represented, and taught, the ideal of “absolute evil,” and the possibility of frustrating G-d’s purpose in creating the human race, but Haman was proud of that! Who else could say that they represented absolute “anything,” except perhaps the Jews, whose ideal was absolute holiness and obedience to HaShem and His Torah.

Haman determined that he was going to return the “favor” to the Jews, and exterminate the entire nation, not just Mordechai, down to the last woman and child!

Chorus: (from a half-remembered children’s song about Purim)

“Oh, once there was a wicked, wicked man,

Hamentashen And Haman was his name, sir!

He would have murdered all the Jews,

Though they were not to blame, sir!”

“Oh today we’ll merry, merry be,

Oh today we’ll merry, merry be,

Oh today we’ll merry, merry be –

And ‘nasch’ some hamantaschen!”

The Persian State Lottery – the “Pur” (of “Purim”)

Haman, ever superstitious, decided to use a Lottery to determine the date of the “Great Execution.” And the Lot fell on the merry month (later, anyway) of Adar. He then approached the King with these diabolical words, “There is one nation scattered and separated among the nations in all the provinces of your Kingdom, and their laws are different from those of every other nation, and the King’s laws they do not observe, and it is not worthwhile for the King to leave them alone.”

“The Removal of the Ring”

Now that’s a very strange statement coming from the mouth of Haman, “It’s not worthwhile for the King to leave them alone”!? After all, why not leave them alone? Who were the Jews bothering?

In any case, Haman proceeded to offer ten thousand talents of silver from his own treasury to Achashverosh for the purpose of funding the operational aspects of his “Solution to the Jewish Problem.” By his next gesture, Achashverosh demonstrated that then, as now, “money talks.”

Achashverosh removed the signet ring from his finger, and gave it to Haman, making him the “Lord of the Ring.” With it, Haman could authorize “Royal Proclamations” as he pleased. Because this ring controlled millions of bloodthirsty Persian and Median swords, the truth is evident of the statement we find, “The removal of the ring of Achashverosh had more effect on Israel (in terms of moving them in the direction of “Teshuvah,” Repentance) than the sixty prophets who prophesied in the time of Eliyahu” (Eichah Rabati, 4:25). Although ironically, it was the disobeying of the prophecies that led to the removal of the ring.

The date is now set: the thirteenth of Adar. On that day, our haters wish to destroy the entire nation of Israel, G-d Forbid. At first, it boggles the mind. Even the Nazis, may their names be erased, needed several years to inflict the damage that they did to our People, and they used “High Technology.” How could an entire nation be destroyed in a single day?

But the answer is simple. The Nazis operated more-or-less out of the public eye. They didn’t publicize the concentration camps, the gas chambers, the crematoria. But in the case of Persia and Media, the entire population of the empire of Achashverosh was to be involved in the bloody work. And everywhere, the Jews were a minority, defenseless without the help of the One Above.

Chorus:

“Oh once there was a wicked, wicked man,

And Haman was his name, sir!

He would have murdered all the Jews,

Though they were not to blame, sir!”

“Oh today we’ll merry, merry be,

Oh today we’ll merry, merry be,

Oh today we’ll merry, merry be –

And ‘nasch’ some hamantaschen!”

Mordechai’s Request

Through his channels, Mordechai knew of what had happened in the palace, the agreement between Achashverosh and Haman about how to deal with the Jews. But he also knew something more important – which he had been told in a dream – that the Heavenly Court had ruled in favor of Haman. Because the Jewish People had derived enjoyment from the Feast of Achashverosh, and worshipped idols time after time, and would not learn the perilous nature of its ways.

He tore his garments and put on sackcloth and ashes, and went into deep mourning. He went into the heart of Shushan and cried out with a great and bitter cry. Esther heard about the mourning of Mordechai and of his greatly altered appearance, and anxiously sent word to find out what the problem was. Mordechai thought, “This must be why HaShem put Esther in the palace.” He informed Esther of the bad news and requested that she go immediately to the King and ask him to rescind the proclamation that spelled disaster for the Jews.

Esther responded initially that even she, the Queen, could not just walk into the chambers of the King uninvited. The Law of the Persian Court was that anyone who did so, for whom the King did not extend his golden scepter to him or her, had forfeited their life.

To which Mordechai responded with the immortal charge, “…Do not imagine to yourself that you will escape in the King’s house from your responsibility to the Jewish People. For if you remain silent at this time, relief and salvation will arise for the Jews from another place, but you and your father’s house will perish; and who knows whether it was not just for this purpose that you were elevated to the palace?”

Esther Rises to the Occasion

That was enough for Esther to hear. Now she and Mordechai would act as a team, and try to raise their fellow Jews to fast and do “Teshuvah,” Repentance, before HaShem. She said that she and her maidservants would fast for three days, and she asked Mordechai to organize a “Ta’anit Tzibbur,” a public fast, in her behalf, to invoke more “Rachamim,” from the Father of Mercy. “U-vechen, “And so, I shall come to the King, though it is not according to the law, and if I must perish, then I will perish.” (Esther 4:16)

The Golden Scepter

On the third day of her fast, Esther donned her royal robes; according to the Midrash, it was the Holy Spirit that clothed her. She stood facing the throne. “The ball is now in the court,” as they say, of Achashverosh. His is the next great decision. The Talmud in Masechet Megila discusses the personality of Achashverosh, as to the question, “Was he a wise King or was he a foolish King?” It seems clear from his next move that at least here he acted wisely. For otherwise, the story of Purim would be very different, and it would be clear to the Talmud that he was nothing but a wicked tyrant.

Achashverosh extended the golden scepter to Esther and she approached the throne. He asked her, “What is your request, Queen Esther? You may request until half of my Kingdom, and your request will be granted.”

What did Achashverosh mean by his enigmatic expression, “up until half of my Kingdom?” RASHI suggests two possibilities, beginning with the Midrashic. According to the Midrash, the reference is to “something that is in the middle and at the center of the Kingdom;” namely, the “Beit HaMikdash,” the Holy Temple. Achashverosh, according to this view, was refusing to grant permission for the Jewish People to rebuild the Temple, but there is a problem with this interpretation:

The King didn’t yet know that Esther was Jewish; therefore, why would he think that she was coming to request his permission for what was purely (not really, but according to his limited understanding) a Jewish interest?

The other interpretation is according to the plain meaning, the “P’shat,” of the text. That his response was the response of a King in love with his Queen, and indeed ready to grant her, in a revolutionary departure from male-dominated practices in ancient (and modern) Persia/Iran, up to half of his Kingdom, actually sharing the Kingdom with her.

Esther’s Request

Esther must have thought long and hard during the days of her fasting about what she would ask Achashverosh in order to accomplish her double objective of saving her People from the immediate danger, and to get rid of the danger that threatened them in the future as long as Haman and his family were alive.

She could not have helped but notice that Haman could scarcely conceal his tremendous ambition for the throne, and that he fancied himself a ladies’ man. She intended to use these two aspects of his personality against him.

She therefore answered the King, “My request is that the King and Haman join me in my chambers for a feast of wine.” As soon as she said this, she saw the early signs of jealousy and fear in Achashverosh’s eyes. “I also plan to reveal to you my nationality and royal origins at the feast of wine,” she continued. The smile of pleasure at hearing that his request to know the nationality of the Queen, and her royal origins, would finally be revealed, enabled him to partially conceal those negative emotions as they played across his face. His voice did not betray him either as he said, “Anything you wish, your Royal Highness.” When Esther had left, he commanded one of his lackeys, “Get Haman immediately and bring him to Esther’s feast.”

The first feast went well enough, but Esther didn’t feel quite ready yet to spring her trap. So that when the King asked her, “What is your request, Queen Esther, and what is your petition? I’ll give you up to half of my Kingdom,” Esther played for time, and asked that there be another feast.

Haman’s Transition

When Haman left Esther’s first feast, he was in a very upbeat mood. But he did a quick about-face. The Megilah says it this way, “And Haman went out on that day joyful and with a glad heart, but upon Haman’s seeing Mordechai at the King’s gate, that he did not rise nor stir before him, then Haman became filled with anger at Mordechai.” (Esther 5:9)

When Haman reached his home, in order to assure himself of his greatness, which Mordechai’s non-recognition seemed to open to question, he gathered his family and closest friends around him. He recited before them all the reasons that he was listed in the “Who’s Who of Persia-Media?” and his most recent accomplishment, that Esther had invited him, and only him, oh yes, the King was also invited, to a feast that she was making.

But Haman said that all his accomplishments and all his possessions were “gor-nischt,” as long as the Jew Mordechai didn’t show him respect! Then Zeresh, his “ezer k’negdo,” the woman who was supposed to be his helper, made a suggestion that seemed helpful at the time: “Let them construct a gallows, fifty “amot” (approximately 75-100 feet high, and that Haman should get up early in the morning, and suggest to the King that this upstart Mordechai be hung upon it. Once you do that, Zeresh concluded, you’ll be able to go to Esther’s feast in a happy mood (unless Zeresh herself, jealous of Esther, was trying to rid herself of Haman). In any case, Haman liked the idea and ordered the construction of the gallows be undertaken (oops! a bad word for Haman, in view of who would actually inaugurate the gallows into full operation, but that’s for the future), immediately.

The Turning Point

“On that night, the King’s sleep went a-wandering” (Esther 6:1), perhaps because of Esther’s unusual invitation of Haman to what he’d assumed would be a private get-together between himself and the Queen. He was afraid not only of losing Esther to Haman, but also of losing his head in a coup. Specifically, he was afraid that someone had once done him a favor, and he had not repaid his benefactor. So he called for the reading of the Chronicles of the Kingdom of Persia and Media.

The reading began with some items that didn’t seem relevant, such as the number of sweaters worn in the Kingdom during the three previous winters, but then came an item that made Achashverosh sit up with a start! Mordechai the Jew had reported a plot on the King’s life to Queen Esther, who had relayed the information to Achashverosh. The plotters had been summarily hung, but nothing at all had been done for Mordechai!

The King tried to think of an appropriate reward: perhaps a hundred maidens, or thirty thousand camels, but somehow nothing he could think of seemed appropriate for the pious Jew. He needed advice, and quickly. Hearing the steps of someone running, he called out, “Who’s in the courtyard?”

And, lo and behold, Haman “just happened” to be in the courtyard, rushing to the King to request permission to hang Mordechai, as the first victim of the new gallows that he had had constructed in his backyard next to the children’s swings. As Haman entered the throne-room, before he had a chance to pose his request, Achashverosh asked, “What should be done for the person whom the King wishes to honor?” (Esther 6:6)

Surprised by the query, Haman soon regained his composure, and formulated a response, based on the obvious assumption that the King meant him. After all, whom else could the King possibly wish to honor? So he let his fantasies run wild! He said, “For the man whom the King wishes to honor, let them bring royal attire which the King has worn, and a horse upon which the king has ridden, and the royal crown that was placed on the King’s head.” (Esther 6:7-8)

“And let the clothing and the horse be given into the hand of one of the King’s Princes, and let him clothe the man whom the king wishes to honor, and let him lead the fortunate person on the horse through the broad streets of the city, and let him proclaim before the honoree, ‘Thus shall be done for the man whom the King wishes to honor.’ “ (Esther, 6:9)

The First Fall

The King, well aware of Haman’s vaulting ambition and jealously suspicious of his intentions regarding Esther, and knowing quite well his hatred for Mordechai, now delivers the first blow to Haman as an unwitting “messenger” of HaShem. The King said to Haman, “Make haste, take the attire and the horse, as you have said, and do so to Mordechai the Jew who sits at the King’s gate; let nothing fall from all that you have said.” (Esther, 6:10)

With nearly complete humiliation, Haman gives that honor to Mordechai. Haman returns to his home in “mourning and great embarrassment” and receives some more uplifting advice from Zeresh, “If Mordechai, before you have begun to fall, is a Jew, know that you will not prevail against him, but you will surely continue to fall before him.” (Esther, 6:13) While they were still speaking, officers of the King arrived to take Haman, willy-nilly, to Esther’s feast.

Esther’s Second Feast

And so the King and Haman came to drink with Esther, the Queen. The King, by now quite impatient, and more than slightly inebriated, asked again, “…Queen Esther, what is your request? I will give you up to half the Kingdom!” (Esther, 7:1-2)

And now, Esther was ready to respond, “If I’ve found favor in your eyes,…, grant my life as my request, and my people as my petition. For we have been sold, myself and my people, to be destroyed, to be slain and to be annihilated; and if we had been sold into slavery, I would have remained silent, but the enemy is not concerned with the damage done to the King.” (Esther, 7:3-4)

Hearing this, Achashverosh went into a fury, and asked, “Who is this enemy, and where is he, whose heart has emboldened him to do this?” (Esther 7:5) And Esther pointed directly at Haman and said, “…this is the enemy, this wicked Haman!” (Esther, 7:5-6)

Chorus:

Oh, once there was a wicked, wicked man!

And Haman was his name, sir.

He would have murdered all the Jews!

Though they were not to blame, sir.

Oh today, we’ll merry, merry be!

Oh today, we’ll merry, merry be!

Oh today, we’ll merry, merry be!

And “nasch” some hamantaschen!

And the King rose in his fury, and stepped out into the palace garden, and Haman rose to beg for mercy from Queen Esther, but he slipped, or tripped or, according to the Midrash, was pushed by an angel, and fell onto Esther’s couch. The King, returning from the garden, took in this lovely scene of Haman sprawled on Esther’s couch, and said menacingly, “Do you dare force the Queen, with me in the house?” When those words came out of the King’s mouth, Haman realized that he was utterly lost, and his face went deathly white with terror!” (Esther, 7:7-8)

And now came the advice that fell upon Haman with the full force of poetic justice, from the mouth of Charvona, one of the King’s advisors, “Haman has said that he made a gallows in order to hang Mordechai. But the King has decided to honor Mordechai. Let us not disappoint the gallows – let Haman be hung from it.” (Esther 7:9-10)

The Ring Changes Hands Again

Now Esther begged Achashverosh to rescind the decree concerning the Jews, “for how can I bear to see the evil that will befall my nation, and how can I bear to see the annihilation of my people?” (Esther, 8:10) But Achashverosh answered that the decrees of the King of Persia and Media could not be rescinded. But he did agree to transfer to Esther and to Mordechai, for Esther had revealed her connection to Mordechai the Jew, the signet ring that was given to Haman, and for them to issue decrees that would in effect counteract the original decrees.

Thus, decrees went out to all the one hundred twenty seven states and provinces of the Kingdom of Achashverosh that were a mirror image of the original decrees, but with a role reversal. For now, the Jews throughout the Kingdom were legally empowered to “assemble and to stand up for their lives; to destroy, to slay, and to annihilate every force of any nation or province that would attack them, and to take booty as well, on one day, in all the provinces of the King Achashverosh, on the thirteenth of the twelfth month, which is the month of Adar.” (Esther, 8:11-12)

Mordechai now was raised by Achashverosh to the level that was formerly Haman’s. “And Mordechai went forth from before the King, in royal attire of blue wool and white…” (the same colors as the modern State of Israel) “…and a large gold crown and a cloak of fine linen and purple wool; and the City of Shushan shouted and rejoiced. For the Jews there was light and joy, and happiness and honor. And in every province, and in every city, wherever the King’s command and his law would reach, there was joy and happiness for the Jews, a feast and a holiday. And many of the people of the land were converting to Judaism, for fear of the Jews had fallen upon them.” (Esther, 8:15-17)

Thus the effect of the original Amalek, who is described in the Torah as “And he did not fear G-d,” (Devarim 25:18) nor the People of G-d, and that was his essence, and the lesson he taught the nations. That lesson was now reversed.

“And it was turned around”

“And on that thirteenth day of Adar, on the day that that the enemies of the Jews hoped to rule over them, it was turned around, that the Jews would rule – they over their foes.” (Esther 9:11)

The ten sons of Haman were hung on the same gallows as their father (Esther 9:7), and the Jews were triumphant in Shushan, the Capital City, and everywhere throughout the Kingdom. And everywhere they triumphed over theirmenemies and, although it was permitted, nowhere did they take from the spoils of war. (Esther, 9:10,14,16)

In the provinces, the battles took place on the thirteenth, and the victory celebrations took place on the fourteenth. In Shushan, the battle was a two-day affair, possibly because of the presence there of a Persian version of the “Republican Guard,” and the victory celebrations were on the fifteenth of Adar. Therefore, Purim in most places is celebrated on the fourteenth of Adar; in ancient walled cities, such as Jerusalem and Shushan (more specifically, those cities that had walls in the time of Yehoshua bin Nun), it is celebrated on the fifteenth of Adar.

Eternal Purim

So Mordechai and Esther moved to make Purim an eternal part of the Jewish calendar. Because the Jews had done “Teshuvah,” they had repented and “accepted again what they had begun to do” (Esther 9:23), they set themselves again on the proper course as HaShem’s emissaries and witnesses in the world. The holiday was called Purim, because “Pur” means “lottery,” and it was by a lottery that Haman determined the date to carry out his evil plan, and it was on that date that his plans were overturned.

Purim turned the month of Adar “from sorrow to joy, and from a time of mourning to a holiday” (Esther, 9:22). The new holiday was comprised of “days of ‘mishte v’simchah,’ ‘feasting and joy,’ ‘mishloach manot ish le-re’ehu,” sending portions of food from one to the other, and last and most important, “matanot la-evyonim,” presents of money to the poor, so that they too could enjoy a joyous Purim.

“The Jews confirmed and took upon themselves and upon their descendants, and upon all who would join them, that it should not be revoked, to keep these two days,…, every year. And these days should be mentioned and kept in every generation, by every family, in every province and city. And these days of Purim shall not pass from among the Jews, and their memory should not cease from their descendants.” (Esther, 9:27-28)