To briefly review, in Part I of this article we introduced the concept that the yearly roster of the special holy-days listed in Vayikra chapter 23 within Parshas Emor might serve as an ‘organizer’ for the kepitlach of Hallel. The seven special times of Emor are: (1) Shabbos; (2) Pesach; (3) Shavuos; (4) Rosh Hashanah; (5) Yom Kippur; (6) Sukkos; (7) Shemini Atzeres.

By focusing upon the words—reflected by their sheroshim—as well as the theme and the tone of each kepitil or section, we demonstrated a one-to-one correspondence between each kepitil or section of Hallel and each sequential holy-day listed in Emor. Specifically:

- 113, מִמִּזְרַח-שֶׁמֶשׁ עַד-מְבוֹאוֹ corresponded to the creation of the Sun, and along with other salient words and concepts, hearkened back to the week of Creation culminating in the first Shabbos

- 114, בְּצֵאת יִשְׂרָאֵל מִמִּצְרָיִם clearly referred to Pesach

- 115:1-11, לֹא לָנוּ יְ-הֹוָה לֹא לָנוּ כִּי לְשִׁמְךָ תֵּן כָּבוֹד, corresponded to Shavuos. Further, we outlined HaShem’s special and personal ‘ownership’ of that yom tov, suggesting that God anticipated its significance and in a sense ‘celebrated’ it even prior to Bri’as Ha’olam

- 115:12-18, יְ-הֹוָה זְכָרָנוּ יְבָרֵךְ , referred to Rosh Hashanah, יוֹם הַזִּכָּרוֹן , and hearkened back to the first Day of Judgment occurring on the 6th day of Creation

- 116:1-11 , אָהַבְתִּי כִּי-יִשְׁמַע יְ-הֹוָה אֶת-קוֹלִי תַּחֲנוּנָי , made for a very good fit summarizing the various activities which occupy the day of Yom Kippur

Up til now things have been pretty straightforward, but here is where it gets a little complicated. As we noted in Part I, the Chumash itself introduces the complexity. Let’s explain:

Note that the roster of the holidays in Parshas Emor is preceded by pesukim of introduction:

ב דַּבֵּר אֶל-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וְאָמַרְתָּ אֲלֵהֶם מוֹעֲדֵי יְ-הֹוָה אֲשֶׁר-תִּקְרְאוּ אֹתָם מִקְרָאֵי קֹדֶשׁ אֵלֶּה הֵם מוֹעֲדָי: ג שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים תֵּעָשֶׂה מְלָאכָה וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ כָּל-מְלָאכָה לֹא תַעֲשׂוּ שַׁבָּת הִוא לַי-הֹוָה בְּכֹל מוֹשְׁבֹתֵיכֶם: ד אֵלֶּה מוֹעֲדֵי יְ-הֹוָה מִקְרָאֵי קֹדֶשׁ אֲשֶׁר-תִּקְרְאוּ אֹתָם בְּמוֹעֲדָם: ה בַּחֹדֶשׁ הָרִאשׁוֹן בְּאַרְבָּעָה עָשָׂר לַחֹדֶשׁ…

Parenthetically, Shabbos seems to be in a category by itself, since unlike the rest of the holy-days, its sanctity is in fact NOT declared by Israel in the Sanhedrin, rather its sanctity is unique and distinct, and is relegated by God Himself. Regardless, note that the the entire listing follows the general introduction of מוֹעֲדֵי יְ‑הֹוָה מִקְרָאֵי קֹדֶש [twice] .

At the end of the entire listing, after the initial mention of Sukkos and Shemini Atzeres, we find quite a similar set of pesukim to bring closure to the entire topic of the holy-days. Even Shabbos is given separate mention, echoing the organization of the opening paragraph:

לג וַיְדַבֵּר יְ-הוָֹה אֶל-משֶׁה לֵּאמֹר: לד דַּבֵּר אֶל-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר יוֹם לַחֹדֶשׁ הַשְּׁבִיעִי הַזֶּה חַג הַסֻּכּוֹת שִׁבְעַת יָמִים לַי-הוָֹה: לה בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ כָּל-מְלֶאכֶת עֲבֹדָה לֹא תַעֲשׂוּ: לו שִׁבְעַת יָמִים תַּקְרִיבוּ אִשֶּׁה לַי‑הוָֹה בַּיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ יִהְיֶה לָכֶם וְהִקְרַבְתֶּם אִשֶּׁה לַי-הוָֹה עֲצֶרֶת הִוא כָּל-מְלֶאכֶת עֲבֹדָה לֹא תַעֲשׂוּ: לז אֵלֶּה מוֹעֲדֵי יְ-הֹוָה אֲשֶׁר-תִּקְרְאוּ אֹתָם מִקְרָאֵי קֹדֶשׁ לְהַקְרִיב אִשֶּׁה לַי-הֹוָה עֹלָה וּמִנְחָה זֶבַח וּנְסָכִים דְּבַר-יוֹם בְּיוֹמוֹ: לח מִלְּבַד שַׁבְּתֹת יְ-הוָֹה וּמִלְּבַד מַתְּנוֹתֵיכֶם וּמִלְּבַד כָּל-נִדְרֵיכֶם וּמִלְּבַד כָּל-נִדְבֹתֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר תִּתְּנוּ לַי-הוָֹה: …

This would seem to be the ideal stopping point for our holy-day roster. However, the Chumash does something unusual here—the paragraph continues with an additional discussion of Sukkos, highlighting additional aspects of the yom tov—almost as if there are two separate aspects of the Sukkos holiday, one of which is completely divorced from the rest of the special days of Emor [pasuk 38 is repeated to emphasize the absence of a parshia/paragraph break]!

… לח מִלְּבַד שַׁבְּתֹת יְ-הוָֹה וּמִלְּבַד מַתְּנוֹתֵיכֶם וּמִלְּבַד כָּל-נִדְרֵיכֶם וּמִלְּבַד כָּל-נִדְבֹתֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר תִּתְּנוּ לַי-הוָֹה: לט אַךְ בַּחֲמִשָּׁה עָשָׂר יוֹם לַחֹדֶשׁ הַשְּׁבִיעִי בְּאָסְפְּכֶם אֶת-תְּבוּאַת הָאָרֶץ תָּחֹגּוּ אֶת-חַג-יְ-הוָֹה שִׁבְעַת יָמִים בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן שַׁבָּתוֹן וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁמִינִי שַׁבָּתוֹן: מ וּלְקַחְתֶּם לָכֶם בַּיּוֹם הָרִאשׁוֹן פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר כַּפֹּת תְּמָרִים וַעֲנַף עֵץ-עָבֹת וְעַרְבֵי-נָחַל וּשְׂמַחְתֶּם לִפְנֵי יְ-הוָֹה אֱ-לֹהֵיכֶם שִׁבְעַת יָמִים: מא וְחַגֹּתֶם אֹתוֹ חַג לַי-הֹוָה שִׁבְעַת יָמִים בַּשָּׁנָה חֻקַּת עוֹלָם לְדֹרֹתֵיכֶם בַּחֹדֶשׁ הַשְּׁבִיעִי תָּחֹגּוּ אֹתוֹ: מב בַּסֻּכֹּת תֵּשְׁבוּ שִׁבְעַת יָמִים כָּל-הָאֶזְרָח בְּיִשְׂרָאֵל יֵשְׁבוּ בַּסֻּכֹּת: מג לְמַעַן יֵדְעוּ דֹרֹתֵיכֶם כִּי בַסֻּכּוֹת הוֹשַׁבְתִּי אֶת-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּהוֹצִיאִי אוֹתָם מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם אֲנִי יְ-הוָֹה אֱ-לֹהֵיכֶם: מד וַיְדַבֵּר משֶׁה אֶת-מֹעֲדֵי יְ‑הוָֹה אֶל-בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל:

Note which details of the yom tov are included in which section. The first section (23:34-~38) seems quite general and nondescript without any mention of what the holiday is all about: it delineates the date of a seven day festival for HaShem called Sukkos, specifies which day work is forbidden, and states that korbonos are brought all seven days of the holiday (which include the ‘Parei HaChag‘ on behalf of the nonJewish Nations, see below). Then, apparently finished with that yom tov, the Chumash moves on to list Shemini Atzeres. The second section (23:~38-43) fleshes out the celebration of the Sukkos with very specific and unique details: it relates it to the celebration of the fall harvest, rejoicing over the Four Species, and introduces the concept of dwelling in the sukkah each year in gratitude for how HaShem sustained our forebears [for forty years] after freeing them from Egypt. Thus, the first section summarizes the sanctity of the day itself (discussing matters and using language in common to the rest of the holy-days), while the second section is focused primarily upon the mitzvos which the individual members of Klal Yisrael must perform upon it, and highlights Israel’s special relationship to it. Interestingly, posukל”ח –which highlights the bringing of [previously] promised korbanos on Sukkos, the final regel of the entire year especially regarding this issue (considered by several opinions to be the deadline to avoid the issur of Baal T’acher, delaying in fulfilling one’s promise to bring a korban, discussed in the Gemarah in Rosh Hashanah 4b[1]) is placed right at the area of division between the 2 sections of Sukkos—so it is unclear which section it more properly belongs in (see footnote 3 below).

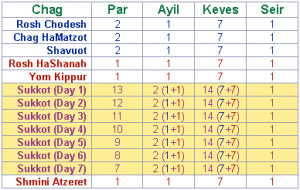

Moreover, take note of the uniqueness of the Sukkos mussafim vs the corresponding korbanos of the other 2 regalim, as well as those of the Yomim Nora’im, as detailed in Parshas Pinchas. (The following discussion is abstracted from “Parshat Pinchas – The Internal Structure of the Holiday Torah Reading” by Rabbi Menachem Leibtag. Table borrowed with his permission.)

Focusing upon the rams and sheep (Ayil and Keves within the chart) Sukkos clearly exhibits a ‘double dose’ of offerings compared with either the other regalim [in blue above] OR the Yimei HaDin, Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur [in red]. Rabbi Leibtag suggests that that may reflect a unique and dual character of Sukkos. It is in one sense a simple regel, part of the Pesach/Shavuos continuum. In a second sense the days of Sukkos are also Yimei HaDin, since the final G’mar of the Din that starts with Rosh Hashanah is not sealed until Hoshanah Rabbah [/Shemini Atzeres]. That is why the prayers for the yom tov include both Hallel (similar to Pesach/Shavuos) and Hoshanos (reflecting the process of Divine Judgment upon rain for the coming year—upon which all human well-being hinges!) [Please see Rabbi Leibtag’s treatment of the 70 bulls of Sukkos in the shiur above for a novel understanding of the total sum consistent with this approach, va’akmal].

The implications of the above analysis lead to a startling conclusion. Sukkos uniquely has important ramifications for all of mankind—for both the Umos Haolam, and for Am Yisrael. For Am Yisrael it indeed has a dual character: it is a time of National thanksgiving (on both an historical and agricultural level) AND of National Divine Judgment; for the other Nations there is NO component of celebratory thanksgiving, but there is most certainly a component of Divine Judgment upon rain—indeed reflected by the 70 bulls of the holiday—offered on behalf of the 70 Nations.

Thus, it is possible that in our Hallel, we indeed take cognizance of that dual nature in our prayers, just as we did in the Mikdash by offering the 70 bulls, on behalf of the other Nations. In other words, perhaps the duplicative treatment of Sukkos at the end of the Parshas Emor holy-day listing reflects the dual nature of the z’man seen in the mussafim of Pinchas—celebratory thanksgiving AND Din for Bnei Yisrael, and Divine Din alone for the Umos Haolam:

סוכות לבני ישראל: תהלים פרק קטז: י”ב-י”ט

יב מָה-אָשִׁיב לַי-הֹוָה כָּל-תַּגְמוּלוֹהִי עָלָי: יג כּוֹס-יְשׁוּעוֹת אֶשָּׂא וּבְשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה אֶקְרָא: יד נְדָרַי לַי-הֹוָה אֲשַׁלֵּם נֶגְדָה-נָּא לְכָל-עַמּוֹ: טו יָקָר בְּעֵינֵי יְ-הֹוָה הַמָּוְתָה לַחֲסִידָיו: טז אָנָּה יְ-הֹוָה כִּי-אֲנִי עַבְדֶּךָ אֲנִי עַבְדְּךָ בֶּן-אֲמָתֶךָ פִּתַּחְתָּ לְמוֹסֵרָי: יז לְךָ-אֶזְבַּח זֶבַח תּוֹדָה וּבְשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה אֶקְרָא: יח נְדָרַי לַי-הֹוָה אֲשַׁלֵּם נֶגְדָה-נָּא לְכָל-עַמּוֹ: יט בְּחַצְרוֹת בֵּית יְ-הֹוָה בְּתוֹכֵכִי יְרוּשָׁלָם הַלְלוּיָ-הּ:

Note the dual nature of the above section with regard to somber, din-like topics and joyous celebratory topics. On the one hand there are aspects reflecting judgment:

- teshuvah (מָה-אָשִׁיב לַי-הֹוָה)

- death (יָקָר בְּעֵינֵי יְ-הֹוָה הַמָּוְתָה לַחֲסִידָיו)

- restrictive bonds of a slave-like servant (אָנָּה יְ-הֹוָה כִּי-אֲנִי עַבְדֶּךָ אֲנִי עַבְדְּךָ בֶּן-אֲמָתֶךָ פִּתַּחְתָּ לְמוֹסֵרָי).

At the other extreme there are celebratory aspects:

- Hashem’s bounty (כָּל-תַּגְמוּלוֹהִי עָלָי), perhaps reflective of the final fruit harvest, and indirectly referring to the mitzvah of lulav and esrog

- salvation (כּוֹס-יְשׁוּעוֹת) perhaps reflective of the Final Salvation in the Y’mos Hamoshiach, consonant with the idea that Sukkos is identified by Chaza’l as the holiday of L’asid Lavo

- release from the restrictions of slavery (פִּתַּחְתָּ לְמוֹסֵרָי )

- Thanksgiving offerings (לְךָ-אֶזְבַּח זֶבַח תּוֹדָה)

- dwelling within the courtyards of the house of God (בְּחַצְרוֹת בֵּית יְ-הֹוָה), not only a reference to the aliyas haregel of Sukkos (בְּתוֹכֵכִי יְרוּשָׁלָם), but perhaps also a metaphor for the mitzvah of dwelling in the sukkah

Heavily laced throughout the section are references to nedarim—which the Gemarah understands are one’s previous nedarim to bring korbanos[2]. As stated above several opinions hold that those must be brought by Sukkos to avoid Baal T’acher—perhaps a mixture of both din and celebration! Those references sync quite nicely with the dividing posuk between the two Sukkos sections in Emor, the posuk from which the Gemarah in Meseches Rosh Hashanah 4b derives the Baal T’acher deadline[3]:

לח מִלְּבַד שַׁבְּתֹת יְ-הוָֹה וּמִלְּבַד מַתְּנוֹתֵיכֶם וּמִלְּבַד כָּל-נִדְרֵיכֶם וּמִלְּבַד כָּל-נִדְבֹתֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר תִּתְּנוּ לַי-הוָֹה:

Thus, we may conclude that the end of 116 is the section of Sukkos, as experienced by Klal Yisrael.

סוכות לעומות העולם: תהלים פרק קיז

א הַלְלוּ אֶת-יְ-הֹוָה כָּל-גּוֹיִם שַׁבְּחוּהוּ כָּל-הָאֻמִּים: ב כִּי גָבַר עָלֵינוּ חַסְדּוֹ וֶאֱמֶת-יְ-הֹוָה לְעוֹלָם הַלְלוּיָ-הּ:

Clearly, the emphasis here is on the nonJewish Nations, and on HaShem’s midah of Gevurah (כִּי גָבַר), reflective of Judgment in a Kabalistic sense. Note the contrast between כָּל-גּוֹיִם in this kepitil and כָל‑עַמּוֹ in the last one[4]! Ironic that the kepitil which focuses upon the nonJewish world in Hallel—is comprised of only 2 small pesukim! And even there, WE—HaShem’s Chosen Nation– make an appearance, insofar that God is גָבַר עָלֵינוּ–overwhelms US with kindness. Consonant with our involvement here is the gematria of the first word, הַלְלוּ –seventy-one; ie the 70 nations, plus Israel, the nation who will be leading them in praise of God in Messianic times. Thus, we may conclude that 117 is the kepitil of Sukkos as experienced by the nonJewish Nations, especially in the time of L’asid Lavo. In this regard, Note the Haftoros of 1st Day Sukkos from Zechariah 14, and of Shabbos Chol Hamo’ed Sukkos from Yechezkhel 38-39—both narratives of the apocalyptic future war of Gog and Magog!

שמיני עצרת: תהלים פרק קיח

א הוֹדוּ לַי-הֹוָה כִּי-טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: ב יֹאמַר-נָא יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: ג יֹאמְרוּ נָא בֵּית-אַהֲרֹן כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: ד יֹאמְרוּ נָא יִרְאֵי יְ-הֹוָה כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: ה מִן-הַמֵּצַר קָרָאתִי יָּ-הּ עָנָנִי בַּמֶּרְחָב יָ-הּ: ו יְ-הֹוָה לִי לֹא אִירָא מַה-יַּעֲשֶׂה לִי אָדָם: ז יְ-הֹוָה לִי בְּעֹזְרָי וַאֲנִי אֶרְאֶה בְשֹׂנְאָי: ח טוֹב לַחֲסוֹת בַּי-הֹוָה מִבְּטֹחַ בָּאָדָם: ט טוֹב לַחֲסוֹת בַּי‑הֹוָה מִבְּטֹחַ בִּנְדִיבִים: י כָּל-גּוֹיִם סְבָבוּנִי בְּשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה כִּי אֲמִילַם: יא סַבּוּנִי גַם-סְבָבוּנִי בְּשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה כִּי אֲמִילַם: יב סַבּוּנִי כִדְבֹרִים דֹּעֲכוּ כְּאֵשׁ קוֹצִים בְּשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה כִּי אֲמִילַם: יג דָּחֹה דְחִיתַנִי לִנְפֹּל וַי-הֹוָה עֲזָרָנִי: יד עָזִּי וְזִמְרָת יָ-הּ וַיְהִי-לִי לִישׁוּעָה: טו קוֹל רִנָּה וִישׁוּעָה בְּאָהֳלֵי צַדִּיקִים יְמִין יְ-הֹוָה עֹשָׂה חָיִל: טז יְמִין יְ-הֹוָה רוֹמֵמָה יְמִין יְ-הֹוָה עֹשָׂה חָיִל: יז לֹא-אָמוּת כִּי-אֶחְיֶה וַאֲסַפֵּר מַעֲשֵׂי יָ-הּ: יח יַסֹּר יִסְּרַנִּי יָּ-הּ וְלַמָּוֶת לֹא נְתָנָנִי: יט פִּתְחוּ-לִי שַׁעֲרֵי-צֶדֶק אָבֹא-בָם אוֹדֶה יָ-הּ: כ זֶה-הַשַּׁעַר לַי-הֹוָה צַדִּיקִים יָבֹאוּ בוֹ: כא אוֹדְךָ כִּי עֲנִיתָנִי וַתְּהִי-לִי לִישׁוּעָה: כב אֶבֶן מָאֲסוּ הַבּוֹנִים הָיְתָה לְרֹאשׁ פִּנָּה: כג מֵאֵת יְ-הֹוָה הָיְתָה זֹּאת הִיא נִפְלָאת בְּעֵינֵינוּ: כד זֶה-הַיּוֹם עָשָׂה יְ-הֹוָה נָגִילָה וְנִשְׂמְחָה בוֹ: כה אָנָּא יְ‑הֹוָה הוֹשִׁיעָה נָּא אָנָּא יְ-הֹוָה הַצְלִיחָה נָּא: כו בָּרוּךְ הַבָּא בְּשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה בֵּרַכְנוּכֶם מִבֵּית יְ-הֹוָה: כז אֵ-ל יְ-הֹוָה וַיָּאֶר לָנוּ אִסְרוּ-חַג בַּעֲבֹתִים עַד קַרְנוֹת הַמִּזְבֵּחַ: כח אֵ-לִי אַתָּה וְאוֹדֶךָּ אֱ-לֹהַי אֲרוֹמְמֶךָּ: כט הוֹדוּ לַי-הֹוָה כִּי-טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ:

Last but not least, we have 118, the kepitil devoted more exclusively to K’nesses Yisrael, and the holiday of Shemini Atzeres. Yet even within this kepitil, we continue themes that have emerged within the last 2 sections, celebration mixed with Din, and tension between Israel and the Umos Haolam. Notice ‘celebration’ words such as

הוֹדוּ, טוֹב, לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ, לַחֲסוֹת בַּי-הֹוָה, קוֹל רִנָּה: זֶה-הַיּוֹם עָשָׂה יְ-הֹוָה נָגִילָה וְנִשְׂמְחָה בוֹ:

vs ‘din‘ words such as

מִן-הַמֵּצַר קָרָאתִי יָּ-הּ, לֹא אִירָא, לֹא-אָמוּת כִּי-אֶחְיֶה וַאֲסַפֵּר מַעֲשֵׂי יָ-הּ, יַסֹּר יִסְּרַנִּי יָּ-הּ וְלַמָּוֶת לֹא נְתָנָנִי

and the tension and contrast present between Jew and nonJew. eg

י כָּל-גּוֹיִם סְבָבוּנִי בְּשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה כִּי אֲמִילַם: …יב סַבּוּנִי כִדְבֹרִים דֹּעֲכוּ כְּאֵשׁ קוֹצִים בְּשֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה כִּי אֲמִילַם:

So what’s going on?

Very simply, Shemini Atzeres represents truly Messianic times AFTER the preceding battle of Gog and Magog, which occurs during the preceding chevlei Moshiach. Therefore it celebrates Yisrael’s victory over the Umos Haolam. In the aftermath of that victory we can truly say with full heart, “הוֹדוּ לַי-הֹוָה כִּי-טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ”!

And the overt connection to Shemini Atzeres? Well, notice the central lines of:

כה אָנָּא יְ-הֹוָה הוֹשִׁיעָה נָּא אָנָּא יְ-הֹוָה הַצְלִיחָה נָּא:

And what is it that we say at the start of every single hakafah on Shemini Atzeres/Simchas Torah??

Hmmm. Oh… yeah.

At the same time, consider the beautiful and moving midrash of ‘kashah olai p’ridaschem‘[5]. The single unique bull-offering of Shemini Atzeres is contrasted with the 70 bulls of the preceding Sukkos—representing the intimate and unique relationship that the king’s son enjoys with his father, at the expense of all the other nations.

But don’t forget whose table the young prince is eating at.

It’s the king’s table, not the son’s. The king’s. And on Shemini Atzeres our Heavenly Father invites US, His ‘son’, “בְּנִי בְכֹרִי יִשְׂרָאֵל[6]“, to dine with Him, at HIS table.

Like Shavuos, Shemini Atzeres is the King’s Day. Not ours. As the kepitil itself states:

כג מֵאֵת יְ-הֹוָה הָיְתָה זֹּאת הִיא נִפְלָאת בְּעֵינֵינוּ: כד זֶה-הַיּוֹם עָשָׂה יְ-הֹוָה נָגִילָה וְנִשְׂמְחָה בוֹ:

Moreover, a further connection to Shavuos can be seen in the parallel structure of pesukim 2-4, at the beginning of 118, vs pesukim 9-11 at the very end of the first section of 115. It seems almost as if 118 picks up exactly where the the section on Shavuos within 115 leaves off, as seen in the table below:

| Beginning of 118 (Shemini Atzeres) | End of 1st section of 115 (Shavuos) |

| ב יֹאמַר-נָא יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: | ט יִשְׂרָאֵל בְּטַח בַּי-הֹוָה עֶזְרָם וּמָגִנָּם הוּא: |

| ג יֹאמְרוּ נָא בֵּית–אַהֲרֹן כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: | י בֵּית אַהֲרֹן בִּטְחוּ בַי-הֹוָה עֶזְרָם וּמָגִנָּם הוּא: |

| ד יֹאמְרוּ נָא יִרְאֵי יְ-הֹוָה כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: | יא יִרְאֵי יְ-הֹוָה בִּטְחוּ בַיהֹוָה עֶזְרָם וּמָגִנָּם הוּא: |

Note the obvious parallelism between the 3 segments of Bnei Yisrael in both kepitlach, further attesting to a special relationship between these 2 kepitlach— and by extension, between Shavuos and Shemini Atzeres—both days that we have postulated more intimately belong to the King[7]!

There is however a slight but significant difference in emphasis between the sections in Hallel reflecting Shavuos and Shemini Atzeres. On Shavuos, it is our privilege and responsibility to give glory to God; it is indeed לֹא לָנוּ. On Shemini Atzeres, it is God’s pleasure—to honor us, through His dinner invitation. Even though both days are uniquely God’s, it is axiomatic in the nature of our loving relationship that it be—reciprocal. And our final response, the ‘sof davar hakol nishma’[8]? הוֹדוּ לַי-הֹוָה כִּי-טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ… for it is indeed HaShem’s Day.

So that brings us to the end of Hallel, and to the end of the Emor holy-days. And looking at the words and themes, the parallels to Parshas Emor appear pretty good. BUT if you’ve been paying attention, you’ve perceived a glaring problem that you’ve been clamoring to ask!

For in the listing of those holy-days in Emor, we do NOT say Hallel in almost half of the list—not on Shabbos, nor Rosh Hashanah, nor Yom Kippur. What gives? Where is the logic of using a list to organize a prayer—which is not said on nearly half the holidays on the list??!

Well, you are not the first to ask that question. Indirectly, the Gemarah does, in Meseches Eruchin, 10b[9]! Answers the Gemarah, that we would indeed say Hallel on those days, absent a few ‘technicalities’–Shabbos is not referred to as a “Mo’ed” in the Chumash [an ‘appointed time’ appointed and set by Israel through the agency of the Sanhedrin] and hence is excluded from Hallel’s recitation; and on the awesome Days of Judgment it is not humanly possible to recite unrestrained praise of God, at the time when the Books of Life and Death are opened for God’s scrutiny[10].

Clearly from the Gemarah’s question, in the absence of those two factors, we would indeed be obligated to say Hallel on all seven holy-days listed in Emor! Logic triumphs after all…

Yet, the Gemarah’s answer raises another question: if fear of Heavenly Judgment precludes singing HaShem’s praises, then how is it that we do say Hallel on Sukkos/Shemini Atzeres? As we noted above, those days clearly also have an integral component of Din?

I’d like to suggest the following approach. It seems to me that the individual Din of the Yomim Noraim has a very different character than the National Din of L’asid Lavo. In Messianic times, the struggle, the legal battle requiring a G’mar Din if you will, is between Bnei Yisrael and the Umos Haolam.

The Gemarah at the beginning of Avodah Zarah provides the specifics of that [future] court case. After multiple arguments from the other Nations are rebuffed, they finally lodge a claim against the Jews of Divine favoritism: after all, we, the Jews, get 613 chances to prove ourselves while they, the Nochrim, just get a measly seven. So they ask for a mitzvah of their own to prove their mettle. Significantly, God gives them the mitzvah of dwelling in a sukkah—A logical choice, for as mentioned above, the nonJewish Nations already have a relationship to the holiday, through their judgment on water, and the 70 bulls brought on their behalf.

But then HaShem does an amazing thing, apparently ‘stacking the deck’ against them. He unleashes the blazing sun, making the sukkah uninhabitable. So they all leave in disgust.

But the Gemarah persists, asking at the top of Avodah Zarah 3b: What’s the point? Even were they Jewish, they should leave under such circumstances: the discomfort of the experience entirely abrogates the commandment, through the halachah of Mitzta’eir[11]. So everyone, Jew and Nocri alike, are patur min hamitzvah. No point in hangin’ around if the mitzvah isn’t there! Why should the other nations be faulted?

But there’s a telling detail that speaks volumes and reveals the lie to their argument.

Although the Gemarah leaves it unspoken, the Jew leaves sadly, unable to celebrate the mitzvah joyously with HaShem, due to circumstance. The Gemarah doesn’t have to say it. That’s what Jews do.

The Nochri storms out in exasperation, kicking the structure as he leaves:

Stoooopid sukkah!!

There is, after all, a very definite point. Sure, the Nochri has a relationship to Sukkos. But his relationship is strictly one of Judgment. He has no relationship whatsoever with the joyous aspects. For him those are as alien as the surface of the moon. God never freed HIS forebears from Egypt and housed them in sukkos! So sitting in the sukkah for a nonJew? A meaningless exercise. That is the point.

HaShem does NOT acquiesce to the other Nations’ request to be tested; He fully understands that such is fruitless. Rather He uses their mitzvah request simply to stage a demonstration so that everyone can finally understand the sad but harsh truth of their own reality:

The Umos Haolam simply don’t have what it takes to be the Chosen Nation of God.

Never did.

Never will.

That’s our place. And our job. Always was.

Indeed, the whole court case is a sham, and—the verdict? A foregone conclusion. It was never in any doubt at all.

So yes, there is an aspect of ‘National Din’ to Sukkos and Shemini Atzeres. But for the Jewish Nation it has a very different character than the individual Din of Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur, The outcome of the Yomim Nora’im din is indeed unknown, terrifyingly one’s entire fate hangs in the balance. Who can sing God’s praises with a full heart under such circumstances?

But the National Din of L’asid Lavo? The only uncertainty there is when the final judgment will come—sadly it appears it will be delayed until we finally show we unquestionably deserve it. As for the verdict itself, there is no doubt whatsoever. In the battle between us and the Umos Haolam—we win. Hands down. It’s a done deal, an open secret.

And God has already ‘leaked’ that verdict to us. So there IS no dread of judgment.

There can be no greater simchah than that, and Hallel is entirely appropriate on those days!

So the next time you say Hallel—think about the totality of the yomim tovim.

Consider how God— Master of the Universe— gives us a whole year full of wonderful holy-days, days in which He rejoices together with us.

And more.

Consider how God —אָבִינוּ שֶׁבַּשָׂמַיִם — has His own holy-days— yet He exclusively invites us to celebrate together with Him.

The two of us are inseparable.

Always were. Always will be.

And let your heart sing.

POSTSCRIPT

When this article was originally conceived and written, it was essentially all conjectural, advanced as hypothesis. No attempt was made to provide support from within Chazal or rabbinic sources for an idea which to me seemed to be novel. That was not by choice; I searched diligently for corroboration, but found nothing convincing.

In the interim, I stumbled across an impeccable source in Parshas Emor which I believe provides strong support for the central thesis—to wit, the Baal haTurim, a rishon. If indeed you harbor some healthy skepticism regarding the validity of our central thesis—read on, in Part III of The Organization of Hallel and Parshas Emor!

Composed largely on the 5th of Sh’vat 5777, the 19th yahrtzeit of my mother, Bede Yaffe ע”ה, Beila d’Raizia bas Baruch HaLevi

A lesson that she lived and taught to me

[1] Actually a 5-opinion machlokes in a braisa—with 2 different opinions citing Sukkos as the deadline in different fashions:

[באחד בניסן ראש השנה למלכים] ולרגלים:

רגלים באחד בניסן הוא? בחמשה עשר בניסן הוא! אמר רב חסדא רגל שבו ראש השנה לרגלים … רבי שמעון אומר שלשה רגלים כסדרן וחג המצות תחלה …רבי אלעזר ברבי שמעון אומר כיון שעבר עליהן חג הסוכות עובר עליהן בבל תאחר

[2] See Meseches Rosh Hashanah 4b, regarding discussion noted earlier.

[3] The specifics of this point are a little tricky and esoteric. By our division criterion, perforce, Section 1 of Sukkos (23:33-~38) must refer to the ‘nonJewish’ Sukkos experience, since clearly Section 2 (23:39-43) describes mitzvos which are unique to Bnei Yisrael, most especially the mitzvah of yeshivas Sukkah, as discussed below. However, if the ‘divider’ between the 2 sections occurs (as is most logical) at the אַךְ at the beginning of posuk 39, then the korbanos mentioned in the Chumash—including the references to זֶבַח in posuk 37 and כָּל-נִדְרֵיכֶם in posuk 38—must be grouped together with ‘nonJewish’ Sukkos. Yet in Hallel these references are found in 116, in the section devoted to ‘Jewish’ Sukkos: יד נְדָרַי לַי-הֹוָה אֲשַׁלֵּם … יז לְךָ-אֶזְבַּח זֶבַח תּוֹדָה… יח נְדָרַי לַי-הֹוָה אֲשַׁלֵּם . However, this difficulty is resolved IF the divider is placed in the middle of posuk 37 after אֵלֶּה מוֹעֲדֵי יְ-הֹוָה אֲשֶׁר-תִּקְרְאוּ אֹתָם מִקְרָאֵי קֹדֶשׁ, although l’chatchilah that would not seem to be its most logical location. (Why Hallel reverses the order of the 2 aspects of Sukkos is not addressed here at all, but see also footnote #5 for a possible contrary interpretation.)

[4] See Rashi on Bamidbar 11:1 :

ויהי העם כמתאננים. (ספרי) אין העם אלא רשעים וכן הוא אומר (שמות יז) מה אעשה לעם הזה. ואומר (ירמיה יג) העם הרע הזה. וכשהם כשרים קרואים עמי שנאמר (שמות ה) שלח עמי. (מיכה ו) עמי מה עשיתי לך:

[5] From Rashi Vayikra 23:36 and Bamidbar 29:36. The actual Tanchuma is as follows:

מדרש תנחומא פנחס סימן טז

אמרו ישראל לפני הקדוש ברוך הוא, רבונו של עולם, הרי אנו מקריבים שבעים פרים לשבעים אומות, לפיכך היו צריכין אף הם להיות אוהבין אותנו. ולא דיים שאין אוהבין אותנו, אלא שונאין אותנו, שנאמר, תחת אהבתי ישטנוני (תהלי’ ק”ט:ד). לפיכך אמר להם הקדוש ברוך הוא, כל שבעת ימי החג שהייתם מקריבים לפני קרבנות, על אומות העולם הייתם מקריבים שבעים פרים. אבל עכשיו, הקריבו על עצמכם, שביום השמיני עצרת תהיה לכם והקרבתם עולה אשה ריח ניחוח לה’ פר אחד איל אחד. משל למלך שעשה סעודה שבעה ימים, וזמן כל בני המדינה בשבעת ימי המשתה. כיון שעברו שבעת ימי המשתה, אמר לאוהבו, כבר יצאנו ידי חובותינו מכל בני המדינה. נגלגל אני ואתה במה שתמצא, בליטרא של בשר או ליטרא של דג או ירק. כך הקדוש ברוך הוא אמר לישראל, כל קרבנות שהקרבתם בשבעת ימי החג, על אומות העולם הייתם מקריבים. אבל ביום השמיני, נגלגל אני ואתם במה שאתם מוצאין, בפר אחד ואיל אחד:

This Tanchuma raises an interesting possibility. In quoting Kepitil 109, “תחת אהבתי ישטנוני” perhaps it is implying that the nonJewish Sukkos experience is found in 116, which starts with אהבתי, contrary to our hypothesis. How might that work out?

[6] Sh’mos 4:22

[7] Note also the exact same parallel with pesukim 12-13 of 115, at the beginning of the section we connected to Rosh Hashanah! Thus Shavuos not only connects to the beginning of the Judgment interval (ie Rosh Hashanah) but also all the way through—to the very end of the Judgment interval on Shemini Atzeres!

Perhaps the more fundamental message is that once we have accepted the Law at Sinai, and have accepted God and His Torah, that establishes a much more intense and intimate relationship, and ‘invites’ God’s more personal scrutiny and judgment of us. Hence the segue directly from Z’man Matan Toraseinu to the whole interval of the Yimei HaDin.

[8] Koheles 12:13

[9] The Gemarah’s actual question has no bearing on Parshas Emor, rather it questions why we do not recite Whole Hallel on those days from an entirely different context, relevant to practices within the Beis Hamikdash .

[10] However it is worth conjecture that perhaps Chaza’l provide an alternative response to the Gemarah’s question. For they assigned Sefer Yonah as the Haftorah for Yom Kippur Minchah . Note Yonah’s ‘Yom Kippur prayer’ from the belly of the Dag in 2:3-10, with special attention to the bolded words:

ב וַיִּתְפַּלֵּל יוֹנָה אֶל-יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהָיו מִמְּעֵי הַדָּגָה: ג וַיֹּאמֶר קָרָאתִי מִצָּרָה לִי אֶל-יְ-הֹוָה וַיַּעֲנֵנִי מִבֶּטֶן שְׁאוֹל שִׁוַּעְתִּי שָׁמַעְתָּ קוֹלִי: ד וַתַּשְׁלִיכֵנִי מְצוּלָה בִּלְבַב יַמִּים וְנָהָר יְסֹבְבֵנִי כָּל-מִשְׁבָּרֶיךָ וְגַלֶּיךָ עָלַי עָבָרוּ: ה וַאֲנִי אָמַרְתִּי נִגְרַשְׁתִּי מִנֶּגֶד עֵינֶיךָ אַךְ אוֹסִיף לְהַבִּיט אֶל-הֵיכַל קָדְשֶׁךָ: ו אֲפָפוּנִי מַיִם עַד-נֶפֶשׁ תְּהוֹם יְסֹבְבֵנִי סוּף חָבוּשׁ לְרֹאשִׁי: ז לְקִצְבֵי הָרִים יָרַדְתִּי הָאָרֶץ בְּרִחֶיהָ בַעֲדִי לְעוֹלָם וַתַּעַל מִשַּׁחַת חַיַּי יְ-הֹוָה אֱ-לֹהָי: ח בְּהִתְעַטֵּף עָלַי נַפְשִׁי אֶת-יְ-הֹוָה זָכָרְתִּי וַתָּבוֹא אֵלֶיךָ תְּפִלָּתִי אֶל-הֵיכַל קָדְשֶׁךָ: ט מְשַׁמְּרִים הַבְלֵי-שָׁוְא חַסְדָּם יַעֲזֹבוּ: י וַאֲנִי בְּקוֹל תּוֹדָה אֶזְבְּחָה-לָּךְ אֲשֶׁר נָדַרְתִּי אֲשַׁלֵּמָה יְשׁוּעָתָה לַי-הֹוָה: יא וַיֹּאמֶר יְ-הֹוָה לַדָּג וַיָּקֵא אֶת-יוֹנָה אֶל- הַיַּבָּשָׁה:

אֲפָפוּנִי is the giveaway, appearing only 4 times in all of Tana’ch! Clearly much of this prayer is taken from Tehilim, and specifically from 116, the kepitil which contains the section we postulate refers to Yom Kippur! So in a sense we ARE reciting the relevant part of Hallel on Yom Kippur! Parenthetically, it’s worth noticing some of the NON-bolded words from Yonah’s tefillah which appear elsewhere in Hallel!

Similar strategies might be employed for Shabbos and Rosh Hashanah. Regarding Shabbos, we have mentioned in Part I footnote 4 the thematic similarities between 113 and 19 (found in Shabbos Pesukei d’Zimra). A much more powerful Hallel ‘substitute’ is found in 135-136 within Shabbos Pesukei d’Zimra:

שבת פסוקי דזמרה – תהלים פרק קלה-קלו הלל

א הַלְלוּיָ-הּ הַלְלוּ אֶת-שֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה הַלְלוּ עַבְדֵי יְ-הֹוָה: קיג:א הַלְלוּיָ-הּ הַלְלוּ עַבְדֵי יְ-הֹוָה הַלְלוּ אֶת-שֵׁם יְ-הֹוָה:

ב שֶׁעֹמְדִים בְּבֵית יְ-הֹוָה בְּחַצְרוֹת בֵּית אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ: קטז:יט בְּחַצְרוֹת בֵּית יְ-הֹוָה בְּתוֹכֵכִי יְרוּשָׁלָם הַלְלוּיָ-הּ:

ו כֹּל אֲשֶׁר-חָפֵץ יְ-הֹוָה עָשָׂה בַּשָּׁמַיִם וּבָאָרֶץ בַּיַּמִּים וְכָל-תְּהֹמוֹת: קטו:ג וֵא‑לֹהֵינוּ בַשָּׁמָיִם כֹּל אֲשֶׁר-חָפֵץ עָשָׂה:

טו עֲצַבֵּי הַגּוֹיִם כֶּסֶף וְזָהָב מַעֲשֵׂה יְדֵי אָדָם: טז פֶּה-לָהֶם… וגו’ קטו:ד עֲצַבֵּיהֶם כֶּסֶף וְזָהָב מַעֲשֵׂה יְדֵי אָדָם: ה פֶּה לָהֶם… וגו’

יח כְּמוֹהֶם יִהְיוּ עֹשֵׂיהֶם כֹּל אֲשֶׁר-בֹּטֵחַ בָּהֶם: קטו:ח כְּמוֹהֶם יִהְיוּ עֹשֵׂיהֶם כֹּל אֲשֶׁר-בֹּטֵחַ בָּהֶם:

יט בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל בָּרְכוּ אֶת-יְ-הֹוָה בֵּית אַהֲרֹן בָּרְכוּ אֶת-יְ-הֹוָה:… וגו’ קטו:יב יְ-הֹוָה זְכָרָנוּ יְבָרֵךְ יְבָרֵךְ אֶת-בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל יְבָרֵךְ אֶת-בֵּית אַהֲרֹן:..וגו’

קלו:א הוֹדוּ לַי-הֹוָה כִּי-טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ: קיח:א/כט הוֹדוּ לַי-הֹוָה כִּי-טוֹב כִּי לְעוֹלָם חַסְדּוֹ:

How about Rosh Hashanah? Please share your ideas!

שו”ע או”ח סימן תרמ סעיף ד

מצטער פטור מן הסוכה, הוא ולא משמשיו (אבל בלילה ראשונה אפי’ מצטער חייב לאכול שם כזית) (כל בו) ; איזהו מצטער , זה שאינו יכול לישן בסוכה מפני הרוח, או מפני הזבובים והפרעושים וכיוצא בהם, או מפני הריח; ודוקא שבא לו הצער במקרה, אחר שעשה שם הסוכה, אבל אין לו לעשות סוכתו לכתחלה במקום הריח או הרוח ולומר: מצטער אני. הגה: ואם עשאה מתחלה במקום שמצטער באכילה או בשתייה או בשינה, או שא”א לו לעשות אחד מהם בסוכה מחמת דמתיירא מלסטים או גנבים כשהוא בסוכה, אינו יוצא באותה סוכה כלל, אפי’ בדברים שלא מצטער בהם, דלא הויא כעין דירה שיוכל לעשות שם כל צרכיו (מרדכי פרק הישן).