On the second night of Pesach (Passover), we start counting seven weeks of the omer (referring to a barley offering that was brought in the Temple). Seven weeks is forty-nine days; the fiftieth day is the holiday of Shavuos (or Shavuot, for those who speak according to the Sephardic pronunciation) - on the 5th of Sivan until sundown of the 7th of Sivan (June 1-3, 2025). Since the word “Shavuos” means “weeks,” the holiday is known in English as the “Feast of Weeks.” (If you look in some old-timey siddurim, you may see it referred to as “Pentecost,” from the Greek word meaning “fifty.”)

What does Shavuos commemorate?

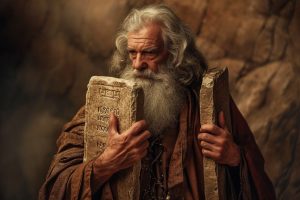

The Jews left Egypt on the fifteenth day of the Hebrew month of Nisan. Seven weeks later, they stood at the foot of Mount Sinai and received the Torah. Shavuos commemorates the revelation at Sinai and the giving of the Torah.

When is Shavuos celebrated?

The date of Shavuos is the sixth day of the month of Sivan. However, unlike other holidays, that date is not explicit in the Torah. Rather, it is calculated by counting from Pesach. According to our standardized Hebrew calendar, Shavuos always falls on 6 Sivan, but in Temple times, when months were determined by witness observation of the moon, it could have fallen a day earlier or later.

Outside of Israel, Shavuos is observed for two days, the sixth and seventh of Sivan. This corresponds to late May or early June on the secular calendar.

How is Shavuos observed?

Unlike the holidays of Pesach and Succos, the Torah does not prescribe any unique mitzvos for Shavuos. On the surface, it’s “just” a “regular” holiday with Sabbath-like restrictions on labor (except for the usual holiday leniencies regarding food preparation and carrying necessary items outside of an eiruv). There are, however, a number of interesting and beautiful practices that are special to Shavuos. These include:

Eating Dairy

There is a widespread custom to eat dairy on Shavuos. There are many explanations for this custom, whose exact origins are lost to history. Perhaps the best-known explanation for the practice is that when the Torah was given, the Jews became obligated in keeping the mitzvos, including the laws of kashrus. Since the Jews hadn’t been keeping kosher prior to that point, their utensils all needed to be kashered (“kosherized”) and they weren’t yet proficient in the intricacies of shechitah (ritual slaughter). Accordingly, preparing meat meals to be eaten on the first Shavuos was impractical. The Jews at Sinai ate dairy, and we emulate them in commemoration (Mishnah Brurah 494:12).

The custom to eat dairy on Shavuos doesn’t completely jibe with the general mitzvah to eat meat on Shabbos and holidays. Accordingly, people address the discrepancy in a number of different ways, such as by eating a dairy kiddush after Shacharis, followed by a meat meal. Others start the meal with dairy, then wash their hands, cleanse their mouths, and eat meat. There are other practices as well.

Staying Up All Night Learning Torah

The contemporary custom to stay up all night learning Torah is attributed to Rav Yosef Karo, the 16th-century codifier of the Shulchan Aruch, though its roots are much older. The Zohar speaks of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who lived in the second century, staying up all night. The ultimate basis for the practice is a Midrash in Shir HaShirim Rabbah to the effect that on the morning when God was to give them the Torah, the Jews slept in, demonstrating a lack of enthusiasm. Throughout the generations, we rectify this national flaw through the many enthusiastic volunteers who spend the entire night engaged in study to show their love of God and their appreciation for the gift of His Torah.

The Arizal, a famous Medieval Kabbalist, organized a selection of Biblical and Talmudic passages into a text called the Tikkun Leil Shavuot (“Order for the Night of Shavuot”). Nowadays, instead of most people go to their synagogues to hear speakers, or to study in small groups or in pairs. Staying up on Shavuot night is not an obligation. It is a voluntary practice, much to be praised, but it’s not for everyone. (So don’t beat yourself up if your constitution doesn’t allow you to pull an all-nighter.) Learn more about the Shavuos all-nighter here.

Reading the Book of Ruth

The Biblical book of Ruth is one of the Chameish Megillos (Five Scrolls) that are read in the synagogue on various holidays. (The most well-known is that we read the book of Esther on Purim.) As mentioned, Shavuos is the anniversary of when the Jews accepted the Torah at Mount Sinai. The book of Ruth tells the story of a woman from the nation of Moab who accepted the Torah, converted to Judaism, and went on to become the ancestor of the kings of the Davidic dynasty. (Additionally, Shavuos is the birthday of Ruth’s descendant, King David.) As if this weren’t enough, the story of Ruth takes place during the barley harvest, which is the time of year when Shavuos occurs. (Another name for Shavuos is chag hakatzir – “the harvest festival.”)

The Biblical book of Ruth is one of the Chameish Megillos (Five Scrolls) that are read in the synagogue on various holidays. (The most well-known is that we read the book of Esther on Purim.) As mentioned, Shavuos is the anniversary of when the Jews accepted the Torah at Mount Sinai. The book of Ruth tells the story of a woman from the nation of Moab who accepted the Torah, converted to Judaism, and went on to become the ancestor of the kings of the Davidic dynasty. (Additionally, Shavuos is the birthday of Ruth’s descendant, King David.) As if this weren’t enough, the story of Ruth takes place during the barley harvest, which is the time of year when Shavuos occurs. (Another name for Shavuos is chag hakatzir – “the harvest festival.”)

Fun fact: The Torah contains 613 mitzvos, which are incumbent upon Jews. Non-Jews are only obligated in the seven universal (Noachide) laws. The numerical value of Ruth’s name is 606 – the number of mitzvos she accepted through her conversion!

Decorating the Synagogue

There is a widespread practice to decorate our synagogues with flowers and other forms of greenery for Shavuos. As with other Shavuos customs, there are a number of explanations for this ancient practice. Perhaps the most famous is based on a Midrash that Mount Sinai bloomed when the Torah was given. This is inferred from the fact that the Jews were warned not to let their animals graze opposite the mountain (Exodus 34:3). Since the Torah was given in an arid wilderness, we see that area must have blossomed when the Torah was given.

The Shavuos Liturgy

Aside from reading the book of Ruth, there are a number of noteworthy features to the Shavuos service. These include:

Hallel – These Psalms of praise (Psalms 113-118, specifically) are sung on Shavuos, just as they are on most Jewish holidays.

Aseres Hadibros – The Torah reading for Shavuos includes the giving of the Aseres Hadibros (literally “the ten statements.” These are commonly referred to as “The Ten Commandments,” but in actuality, these ten statements include fourteen commandments!). As Shavuos commemorates the revelation at Sinai, we recreate that event in microcosm.

Aseres Hadibros – The Torah reading for Shavuos includes the giving of the Aseres Hadibros (literally “the ten statements.” These are commonly referred to as “The Ten Commandments,” but in actuality, these ten statements include fourteen commandments!). As Shavuos commemorates the revelation at Sinai, we recreate that event in microcosm.

Akdamus – The practice in most Ashkenazic communities is to recite Akdamus Millin, a lengthy liturgical poem, as a preface to the Torah reading. Written in Aramaic by Rabbi Meir bar Yitzchak of Orléans (d. 1095), the poem entered the liturgy early in the 15th century. Akdamus is 90 verses long. The first 44 of which comprise a double acrostic. The subject of the poem is God’s greatness, the various types of angels that serve Him, how God is the source of the Jewish people’s strength, how God will reward the righteous, and an assurance that the listener will be so rewarded if they God’s Torah.

Yizkor – On the second day of Shavuos (or, in Israel, the one day), this memorial prayer for departed relatives and martyrs is recited, as it is on many other holidays. (Full information on Yizkor is available here.)

And that’s the holiday of Shavuos in a nutshell. But there’s so much more to learn! Be sure to browse OU Holidays for all your Shavuos information and inspiration!