This shiur provided courtesy of The Tanach Study Center

In memory of Rabbi Abraham Leibtag

Are the ‘Four Sons’ really in the Bible?

When we quote that Midrash at the Seder, we certainly get that impression, for the Haggada quotes a pasuk from Chumash as the source for each son. However, when you take a closer look at that Midrash, you’ll immediately notice that when it does quote Chumash, it doesn’t seem to be very ‘accurate’.

So, is the Midrash wrong?

Of course not! However, to appreciate its message – the reader must realize that this Midrash is not explaining Chumash, rather it is using pesukim from Chumash to develop a beautiful message. [Quite often, that’s what Midrash is all about!]

Therefore, to uncover the deeper meaning of the Midrash of the Four Sons, we will first study “pshat” to find the ‘real’ reason for why there are ‘four sons’ in the Chumash; that will enable us to appreciate what Chazal intended to teach us by way of their beautiful “drash”.

[It should be noted that the Midrash of the four sons that we quote in the Haggadah is actually a Mechilta, and also found in the Talmud Yerushalmi – See Haggadah Sheleima by Rav Kasher for complete set of sources and versions.]

Introduction

Let’s begin by quoting the opening line of this Midrash, and translating it into English:

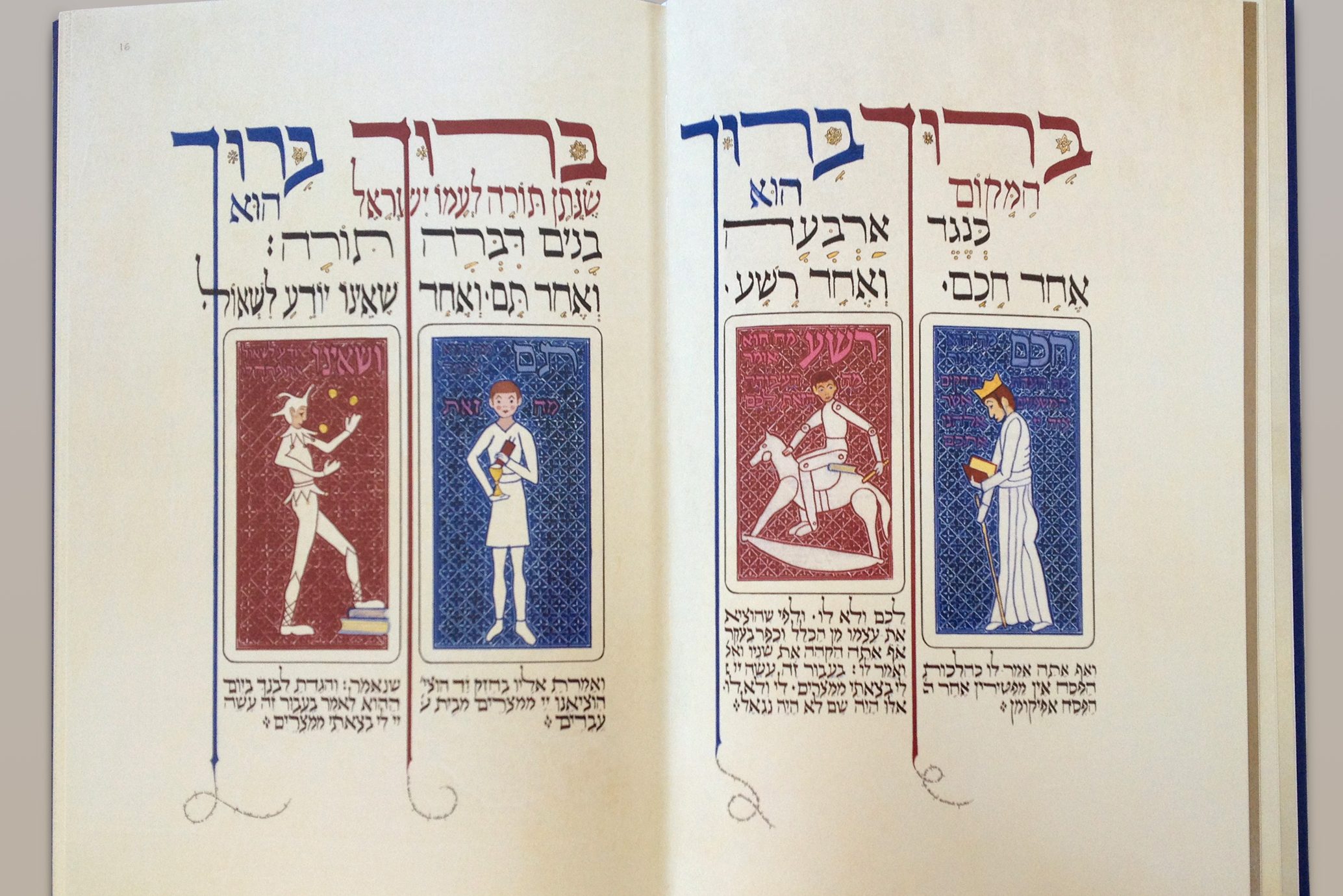

“Keneged arba’ah banim dibberah Torah” [Corresponding to Four Sons – the Torah spoke]

1) echad chacham – the wise son;

2) ve’echad rasha – the wicked son;

3) echad tam – the simple son;

4) ve’echad she’eino yodea lish’ol – the son who doesn’t know how to ask

The Midrash continues by quoting a question for each son -from the four instances in the Torah when a father answers his son [i.e. when a parent answers his child].

As it is commonly presumed that these four quotes all pertain to questions about Passover – the assumption is that it would have been enough had the Torah only recorded only one ‘question and answer’. But when we notice that the Torah provides us with four different versions of ‘questions and answers’ – we assume that each version ‘corresponds’ to a different type of son. Based on this understanding, the Torah is simply providing us with ‘prepared answers’ for four different personalities of children.

This also seems to be what the Midrash implies by its opening statement “k’neged arba banim dibra Torah” – that the four times that the Torah discusses a parent answering a child – ‘corresponds’ to these four types of children.

However, to our surprise, when we compare the answers given by the Haggada to these four questions – to the answers provided in Chumash, we find many discrepancies!

Therefore, this original assumption must be incorrect! [Unless we conclude that the Haggada isn’t quoting Chumash properly – which obviously cannot be.]

In the following shiur, we will first study the various pesukim that this Midrash quotes, while paying careful attention to their original context. By doing so, we hope to arrive at a deeper understanding of its message.

Comparing Answers

As we explained, the four questions are direct quotes from Chumash, however – the answers that the Haggada provides are very different than those given by Chumash.

To illustrate this, let’s compare these answers – one question at a time, noting the obvious differences:

The WISE son’s question:

“Mah ha’edot vehachukkim vehamishpatim asher tzivah Hashem Elokeinu etchem” ? [What are the laws… that God has commanded us?] (see Devarim 6:20)

- Answer in Chumash:

“avadim ha’yinu l’pharoh b’mitzraim ….” [ Tell your son: We were once slaves to Pharoah and God took us out etc…] (see Devarim 6:21-25 for the full answer) - Answer in Haggada:

” Ve’af attah emor lo k’hilchot haPesach, ein maftirim achar hapesach afikoman.” [Teach him the laws of the pesach… -most likely this refers to the tenth chapter of Masechet Pesachim – teach him until the last mishna re: afikomen ]

The WICKED son’s question:

“Mah ha’avodah hazot lachem?” [What’s this service to you?]

- Answer in Chumash:

“v’amar’tem zevach pesach hu l’Hashem asher pa’sach al batei bnei Yisrael b’Mitzrayim…” [Tell your son that this is the Paschal offering – for God had passed over our houses when He smote the Egyptians…” (see Shemot 12:27) - Answer in Haggada:

“v’af atta hakheh et shinnav ve’emor lo:’ba’avur zeh asah Hashem li betzeiti m’Mitzraim’ … [Even you should break his teeth – and tell him if people like him were living at that time – he would not have been worthy of redemption…]

The SIMPLE son’s question:

” Mah zot?” – What is this [about]?

- Answer in Chumash:

“Bechozek yad hotzi’anu Hashem m’Mitzrayim m’beit avadim. V’yhi ki hiyksha Pharoh l’shalcheinu -va’yaharog kol bchor b’eretz Mitzraim, m’bchor adam ad bchor b’haymah” – [God took us out of Egypt from the house of slavery, and when He took us out, God killed their first born… and therefore I am dedicating the first born of every womb to God…”

(see Shemot 13:14-16) - Answer in Haggada:

“Bechozek yad hotzi’anu Hashem m’Mitzraim mibeit avadim.” – God took us out of Egypt with an outstretched Hand – [but nothing more! In other words, we only quote the first phrase of the answer.]

The son WHO DOESN’T KNOW TO ASK’s question:

As there is no question in Chumash, the Midrash only quotes the Torah’s answer of “vehiggadta livincha bayom hahu lemor, ‘ba’avur zeh asa Hashem li betzeiti mimitzrayim.'” (see Shemot 13:8). Therefore, the Midrash cannot provide a different answer, since the question (or lack of one) is implicit from the answer.

Instead, the Midrash notes this instance in Chumash where we are commanded to explain something to our children, even though it was not preceded by a question. The Midrash identifies this son as the one who doesn’t know how to ask.

[As there is only an answer, we can not expect to find a discrepancy between Chumash and the Haggada for this son.]

This simple comparison between the first three of the four sons, immediately confirms that the answers in Chumash are very different than those in the Haggada.

So why can’t the Midrash quote Chumash correctly?

Different Topics or Different Sons

The reason why is rather simple. If we examine these four questions in Chumash, and study their context, we will indeed find four questions, but each question relates to a different TOPIC – not to a different son!

To prove this, let’s return to each question, noting its context in Chumash: [Be sure to have a Chumash handy, to follow along.]

The WISE son’s ‘topic’: the Entire Torah

Take a quick glance at Devarim chapter six, noting how it introduces a complete set of laws that Moshe Rabbeinu is about to teach. See 6:1, note also 5:1, 5:28, and especially 4:45 – as they are all pesukim that introduce this same set of laws. Note as well that the pesukim that we say every day in Shema (4:4-8) are part of this same introduction.

As this set of laws that Moshe is teaching will continue for some twenty chapters (from chapter 6 thru 26), the opening section deals with the underlying reason for these laws. In this context, Moshe Rabeinu ‘anticipates’ in 6:20:

“Should your child ask you: ‘what [is the reason for] these ‘eidot chukim u’mishpatim’ that God is commanding us?” (see 6:20/compare with 4:45!)

Then, the Torah tells us to answer our child as follows:

“We were once slaves in Egypt, but God took us out with a strong arm… and God took us out – in order to bring us to the land that He promised to our forefathers. And He commanded us to keep these laws to fear Him, and for our own good… ” (see Devarim 6:21-25)

Obviously, this ‘question & answer’ has nothing to do with the personality of any type of son. [If any, it sounds more like a ‘wise guy’ asking, more so than a ‘wise son’!]

In fact, this question sounds like a very logical one that almost any child will (and should) ask, when confronted with the obligation to keep a complete set of laws that govern every walk of life. Furthermore, this question is not about the Seder, nor about Passover! It’s a question about the very reason for why we are charged to keep the entire Torah!

[Note how in the Haggadah we use the first line of this answer (“avadim hayinu…”) to answer the “mah nishtana”. Based on the context of these pesukim, it is a very meaningful starting point to begin our explanation for the Exodus in Maggid.]

The Wicked son’s ‘topic’: Korban Pesach

Return now to Sefer Shemot chapter 12, and take a quick glance noting how it begins with “Parshat haChodesh” (12:1-20), – that describes the laws of the ‘korban Pesach’ in Egypt; and continues with Moshe Rabbeinu’s instructions to the people (see 12:21-28), including the commandment to offer a similar ‘korban Pesach’ on a yearly basis, once they arrive in the Land of Israel (see 12:23-26). In that context, we find yet another very logical question, that any son could (and should) ask:

“When you come to the land… keep this service [of korban Pesach] – and it shall come to pass when your children will ask you: ‘What is [the purpose] of this service to you’ – then you shall explain: ‘ This is a Passover offering for God, [to remember how] He passed over the houses of Israel, when He smote the Egyptians…” (see 12:24-27)

Once again, a very logical question, followed by a very logical answer, concerning the topic of KORBAN PESACH.

Without ‘reading in’ to the words of this question, there is no reason to assume that Chumash is talking about a ‘wicked son’. In fact, it seems that Chumash expects (and wants) our children to ask this question!

The SIMPLE son’s ‘topic’: KEDUSHAT BECHOR

Let’s continue our study by jumping to Shemot chapter 13, noting the parshia that begins in 13:11 (thru 13:16), that records the laws relating to “kedushat bechor” [the holiness of the first born] – that the first born of both humans and animals should be dedicated to the service of God (see 13:11-13). At the conclusion of those laws, the Torah anticipates once again a question from an inquisitive child, this time asking “mah zot” -[what is this all about (see 13:14). As this question concerns specifically the topic of the ‘first-born’ – the Torah proposes an answer that relates exactly to that question:

“And tell him [your son] – God took us out of Egypt from the house of slavery, and when He took us out, God killed their firstborn… therefore I am dedicating the male first born of every womb to God…” (see 13:15-16)

Once again, the topic is not about the Seder or Passover; rather the topic is “kedushat bechor”. Indeed, this time the question is much shorter than in the first two instances; nonetheless – the reason for this additional question is because of the additional topic – and not necessary because he is a ‘simple son’.

The DOESN’T KNOW TO ASK son’s ‘topic’: Eating Matzah

Let’s return now to the beginning of Shemot chapter 13, and quickly review from 13:3-8, noting how these pesukim discuss the commandment to remember the Exodus by eating matza for seven days (and by not eating chametz).

[Note as well how 13:1-2 actually belongs with 13:11-15 – a topic that was discussed in our TSC shiur on Parshat Bo; and beyond the scope of this shiur.]

After detailing the laws concerning eating matza for seven days, while not owning or seeing any chametz (see 13:6-7), the Torah concludes with a commandment that we must explain why to our children even if they don’t ask:

“And you shall tell you son on that day, for the sake of this [matza] God did for me [these miracles] when I went out of Egypt” (see 13:8)

The commandment to remember the Exodus is so important that Chumash demands that we explain why to our children, even if they don’t ask. In “pshat”, this doesn’t imply that we are dealing with a child that doesn’t know how to ask; it is simply because this mitzvah is of cardinal importance!

[This is supported by Rashi & Ibn Ezra’s interpretation – that this pasuk implies that we explain to our children that God took us out of Egypt in order that would be able to keep all of His mitzvot!.]

To summarize our study, the following table summarizes how the four instances in Chumash where the father answers his son relates to a unique topic, even each topic does relate in one form or another to the Exodus.

| QUESTION | CONTEXT | TOPIC |

| Shemot 12:26 | 12:21-28 | Korban PESACH. |

| Shemot 13:8 | 13:3-10 | Chag HaMATZOT. |

| Shemot 13:14 | 13:11-16 | Ke’dushat BCHOR. |

| Devarim 6:20 | 6:1-25 | ALL the MITZVOT |

None of these questions are ‘superfluous’, as each question deals with a specific topic. Therefore, according to ‘pshat’ there is no necessity to relate these four questions to four different types of children, rather – there are four questions in Chumash because there are four topics in Chumash!

Could it be that the Midrash is unaware that each question relates to a different topic?

We posit exactly the opposite – that the Midrash is fully aware of the “pshat” and expects that the reader is intelligent enough to figure it out on his own. However, as is often the case, the Midrash is not coming to teach us the “pshat” of Chumash, rather it is ‘using’ pesukim in Chumash to convey a thought; or in our case – an educational message.

In our specific case, the Midrash of the ‘Four Sons’ is interested in giving over an insight relating to education, a thought that carries special significance at the Seder, following the guideline of the Mishna that:

“k’daat ha’ben, aviv m’lamdo” – According to the level of the son – the father should teach (or tell over) the story.

(see Mesechet Pesachim – 10th chapter)

The Midrash wishes to expound upon this educational principle. In a very clever style, the Midrash first ‘borrows’ the four questions mentioned in Chumash when a father answers his son, quoting them totally out of their original context, and turning them into questions about the Seder.

As the original wording of each of these four questions in Chumash is quite different, the Midrash utilizes this to attach an identity to each question, conforming to four different types of children.

Then, to convey its educational message, the Midrash composes a special answer for each son, which relates specifically to his personality (and not to its original topic in Chumash).

For example, in the wise son’s question, the phrase “mah ha’eidot” is interpreted as ‘what are the laws’ [of the Seder], while in Chumash it means ‘what is the purpose of these laws’ [of the entire Torah]. Therefore, the answer to this question in the Haggada is totally different than the answer in Chumash.

Similarly, to turn the wicked son’s question into a real ‘wicked son’ – the Haggada must first add some inflection into his voice, making the word “lachem” [‘for you’] more emphatic – to emphasize his attitude problem. Therefore, the answer once again is not the same as the one in Chumash, instead the Midrash ‘borrows’ its wording from elsewhere in Chumash: “ba’avur zeh asa Hashem LI” (see Shemot 13:8) – once again adding inflection, this time emphasizing the word “li” – for ME and not for YOU.

For the simple son’s question “mah zot” [What is this?] – the Midrash finds no need to make an alteration. However, since this question in the Midrash is about the Seder, it truncates the answer provided by Chumash (about kedushat bechor), quoting only the first phrase – in order to keep it short, and relevant only to the Seder (see 13:14-15!).

In essence, the Midrash provides us with four examples of how to ‘read between the lines’ of a question in order to discern the character of the son who is asking.

For Parents and Teachers

In real life, when the parent hears the question of a child; or when the teacher hears the question of a student; he must listen carefully not to the QUESTION, but also to the PERSON behind the question. To answer a question properly, the parent must not only understand the question, but must also be aware of the motivation behind it. Hence, his answer must not only be accurate, but also appropriate, as it must relate to the child’s character while taking into account his spiritual needs.

The parent (and teacher) must listen carefully to the voice behind the question, evaluate and answer appropriately. When necessary he can even innovate, just as the Midrash does!

This message conveyed by the Midrash of ‘the Four Sons’ in the Haggada is not only the responsibility of every parent, but also the challenge of every teacher. Understanding it correctly enables us to pass down our tradition from father to son, our heritage from generation to generation; certainly a Midrash worth quoting at our Seder Table.