Everyone who lives in Jerusalem – especially those like me who were born here – is in love with the city, really in love. For us, it is not just a place, not just a house; it is a home. But it is even more than that: It is an object of love. Even visitors are in some way ensnared by Jerusalem. So many of their hearts are captured, but in different ways, for different reasons. Why is it so?

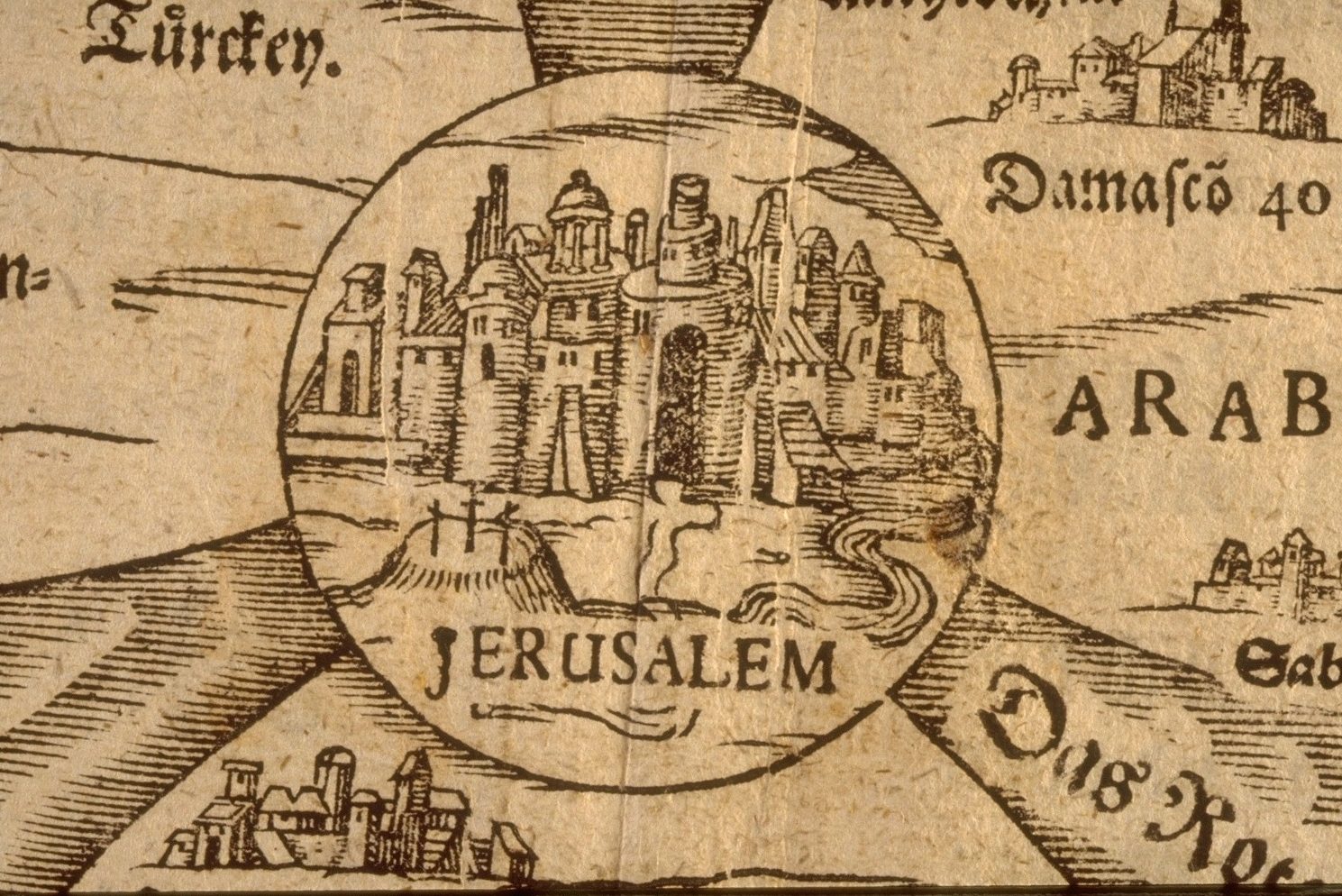

Jerusalem is many things to many people, because it is – and always has been – a kind of enigma. It is a place that is composed of many parts. They may seem to clash with one another, but somehow they achieve a kind of harmony that is felt by anyone who walks her streets or breathes her air or soaks up her sunshine.

Jerusalem is simple, but not naïve. Jerusalem is simple in a most sophisticated simplicity, because Jerusalem has passed sophistication. It is a very old city. It is a city that has suffered much and has known so many things that it is now very simple, like some of those great masterpieces. The simplicity hides so many things. You look at it, you dream about it, and you think, what really is it?

Jerusalem is also, in many ways, a combination of contradictions: It is called, and its name itself implies, “City of Peace,” yet so many wars took place here. It is perhaps one of the most quarrelsome and troublesome places in the world, but it is still a city of peace. There is a saying, especially in Jewish tradition, that it is “the house of God.” The gate to heaven is understood to refer to Jerusalem, but Jewish tradition also identifies the valley of Gehinom (hell) near the walls of the Old City.

This is Jerusalem. This is what the Psalmist described as ir she’chubra lah yahdav, a city that was joined together. It is not just joined together because there is old and new, or because it is home to religious and non-religious, Arabs and Jews and Christians. It is a place that combines differences and brings them, somehow, together in a kind of harmony of contradictions. And there is another explanation, which seems very beautiful to me, that the name Jerusalem comes from yir’e shalem, which may be translated as “a complete view,” another form of harmony.

It is historically, and perhaps theologically, significant that Jerusalem is unlikely as the site of a capital. It is not on a road, or on a river, or near the sea. It is somewhere …in nowhere. Even so, it is a center – the place the Bible tells us that God chose. But why?

In life, as in geology, there are many strata: of substance, of meaning, and of energy. And in life, as in geology, there is physical causality, in which things move and are understood according to physical laws and reasoning. This physical causality – which some might call “real life” – is one level of existence.

There is also another, higher and very different level of causality – a spiritual one – in which there are rewards and punishments for good and evil. Usually, there are no connections between the physical and spiritual strata; they don’t mix. People may move from one level to the other, but they don’t mix. But there are – in spirituality, as in geology – points at which the levels touch, where two strata of existence somehow come together in one point, like a corner formed by two walls. The corner has no substance of its own, but – like a lap – exists because of the relationship of two other planes. This juncture is what Jacob called the ladder or gate to heaven, a place where influence, power, and insight can move either way, between the spiritual and material worlds.

Such a point is Jerusalem.

No one knows why it should be so, but Jerusalem is a fault-line in the stratification of the world order. Just as water may spurt forth from a geological fault, so, too, Jerusalem is a gushing wellspring of existence, a source of goodness and benefit. Because this point where the physical and spiritual worlds meet is the place where they can work together, things happen in Jerusalem that do not conform to ordinary rules. Here, more than anywhere else, the smallest events take on a cosmic meaning and enigmatic complexity that are beyond our understanding.

An event that happens in Jerusalem reverberates all over the world, yet a similar incident elsewhere passes almost unnoticed. Only here does the causality of the material world become entangled with the entirely different causality of the spiritual world. The energy of justice and the energy of power are pulled toward Jerusalem, as toward a lightning rod, and become entangled, sending shock waves around the globe.

Jerusalem is a place of power and resonance, waiting – perhaps hoping – for a voice that will be heard all over the world, a voice that will renew the message of peace and wholeness and holiness that has always issued from this holy city.

At this time of year, we mourn for Jerusalem, not as we mourn a relative – emerging, in stages, from our sudden grief: shiva to sheloshim to the 11 months of avelut. Rather, in keeping with Jerusalem’s contradictions, we descend into mourning gradually: from the Three Weeks to the Nine Days to Tisha B’Av. We have no hope of seeing our loved ones again; the stages of mourning mark our fading, but always lingering, memories. As we mourn for Jerusalem, however, we hold out hope that we will see mourning swept away forever, by its peace and wholeness and holiness.

–Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz is a prolific author, scholar, and social critic best known for his monumental translation and commentary on the Talmud. He is also the founder of a worldwide network of Jewish educational institutions that are supported by the Aleph Society. His most recent book, We Jews: Who Are We and What Should We Do?, was published earlier this year by Jossey-Bass: Wiley. To learn more about the work of Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, visit www.steinsaltz.org.