“Your People is my People, and your G-d my G-d” (Ruth 1,16)

“Your People is my People, and your G-d my G-d” (Ruth 1,16)

What is the Story of Ruth?

Our story begins in the Land of Israel, during the Period of the Rule of the Judges, leaders of the Jewish People who preceded the Kings, towards the beginning of their national residence in the Land of Israel. The set of characters initially is Elimelech, his wife Naami and their two sons, called Machlon and Kilyon, though it is doubtful that these are their real names, because those names mean “destruction,” and it is doubtful that any parents would give their children such names.

The Story of Ruth is also the classic Jewish “mother-in-law”-“daughter-in-law” story, in that it is the story of a relationship of great love, loyalty and devotion which develops between the two female heroines of the story.

The family of Elimelech has moved to the “fields of Moav” in order to escape the effects of a famine which has broken out in the Land of Israel. This does not sound like an extremely worthy or public-spirited thing for Elimelech and his family, who were quite affluent, to have done, and perhaps that is why Elimelech and his two sons died in Moav, after the sons had married into the royal family of that country.

News comes from Israel that the famine has lifted. Naami, feeling nearly totally bereft, decides to return to her home in Beit Lechem, Yehudah. Her two daughters-in-law, Orpah and Ruth, say initially that they want to remain with her and return to the land they have never seen, and to the Jewish lifestyle. Naami discourages them, telling them of the difficulties of Jewish life, and that they would definitely be better off if they returned to the palaces from which they’d come. It is from here, incidentally, that we learn the attitude of Judaism towards potential converts, namely “Let your left hand push away while your right hand attracts.”

Orpah eventually decides to leave, but Ruth will not be dissuaded, and says to Naami, “Do not urge me to leave you, to go back from following you – for wherever you go, I will go, where you lie down, I will lie down. Your people is my people, and your G-d is my G-d. Where you will die, I will die, and there be buried; may Hashem punish me greatly if I allow anything but death to separate between me and you.” (Ruth 1:16-17)

Naami accepts her sincerity and agrees to allow Ruth to accompany her on the road back to Beit-Lechem. When the two women arrive, the townspeople hardly recognize Naami, for she left as a wife, and as a mother, of a very affluent family. But now she has been reduced to poverty and loneliness. Naami says to them, “Don’t call me Naami [which means “pleasantness”], for Hashem has (justifiably) made my life bitter.”

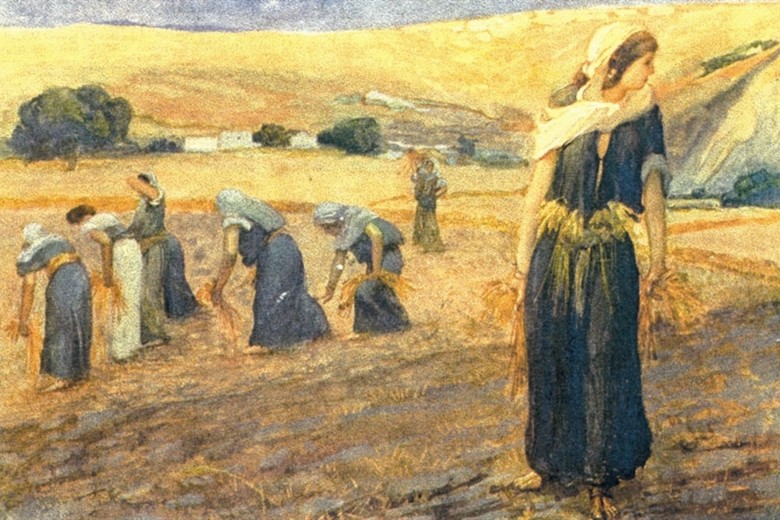

Lacking any other source of income, Ruth offers to become a gleaner, picking up grain behind the cutting crew in the fields with the other poor, according to the Law of the Torah. Naami agrees to let her do this.

When Ruth chooses a field among the many possibilities to glean in, the Megillah uses an expression which is probably a thinly-veiled reference to “hashgachah pratit,” supervision by Hashem over events in the lives of individuals, a basic assumption of the Jewish faith. The verse says, ironically, she “just happened” to find herself in the fields of Boaz. Now this Boaz was a great scholar in Israel, and was also a relative of the deceased Elimelech, which placed him in line to be a “redeemer” of the property of Elimelech, and to marry Ruth, according to the Laws of the Torah – with one problem!

The Torah excludes the nations Amon and Moav from eligibility for marriage within the Jewish People, because they had denied bread and water to the Jewish People when they wanted to travel through their territory on the way to the Land of Israel. Not only that, but Balak, the King of Moav, had also hired the Midianite Prophet, Bilaam, to curse the Jewish People, because that was his specialty. This would have excluded Ruth, a Moabite princess, from the possibility of marriage with Boaz, if not for a little known oral tradition which excluded female Moabites and Amonites from the marriage-exclusion principle, because they had not participated in any way in the anti-Israel crimes mentioned above.

Ruth begins to work in the fields of Boaz. Boaz arrives in the fields, greeting his workers with “May Hashem be with you!” and receiving the response of “May Hashem bless you!” His attention is attracted by Ruth because she is going about her business in a very quiet, modest manner, unlike the behavior of the other gleaners. He learns her identity from the foreman of the fields, and invites her to remain on his fields till the end of the harvest.

When Ruth returns to Naami, and informs her where she has been working, Naami realizes that Hashem has been working here from behind the scenes to bring Ruth and Boaz together. At the end of the harvest, she advises Ruth to dress in her finery and go to Boaz, who is working in his threshing barn, to ask him during the night to be the redeemer of the property of Elimelech, and to marry Ruth. Ruth agrees to do so.

In the middle of the night, Boaz realizes that a woman is present, and asks her, in the dark, to reveal her identity. Ruth does so, and makes her request. In formulating his response, Boaz decides that it is time for the male/female distinction with regard to the Moabite exclusion to become more widely known.

However, there was another Jew who was a closer relative, and who therefore was first in line to be the redeemer. This individual, at this stage in the story, is referred to by the name “Tov,” which may or may not, again, have been his real name but, in any case, means “good.” When a person still has the opportunity to fulfill a responsibility, he is considered good. However, when confronted with the possibility of redemption, and advised that Ruth is also involved, Tov declines to accept the role because he is afraid to get involved with the Moabite controversy, and is referred to as “Ploni-Almoni,” Mr. So-and-So.

When Boaz heard the refusal of Ploni-Almoni, he announced that he himself was ready to act as the redeemer. He invited ten people to be witnesses to the wedding (from which we learn that ten witnesses are required to be present at a wedding). The congregation blessed the couple: Boaz, the great scholar and leader of Israel, himself one of the Judges, and Ruth, the modest and kind convert to Judaism, who had come from Moav out of love for Naami and for the Torah of Naami.

Soon after the marriage, a son was born to Ruth, and Naami took the child in her bosom. The neighbors said, “A child has been born to Naami,” because the mother was Ruth, a daughter-in-law who was more loyal and devoted to Naami than “seven sons.”

And they called the name of the son “Oved,” which means “one who worships,” who was the father of Yishai who, in turn, was the father of “David HaMelech,” King David. David, descendant of Ruth, would later meet “Galyat,” Goliath, the Giant, descendant of Orpah, on the battlefield between the Philistines and the People of Israel. When Galyat would curse the Jewish People, David would rise up against him, empowered by the Name of the G-d of Israel Whom Galyat had blasphemed, and slay him. It is King David, who was able to combine the characteristics of a great warrior and of the “sweet singer of Israel,” from whose descendants ultimately will emerge the “Melech HaMashiach,” the Anointed King, the Redeemer of Israel.